From the April 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

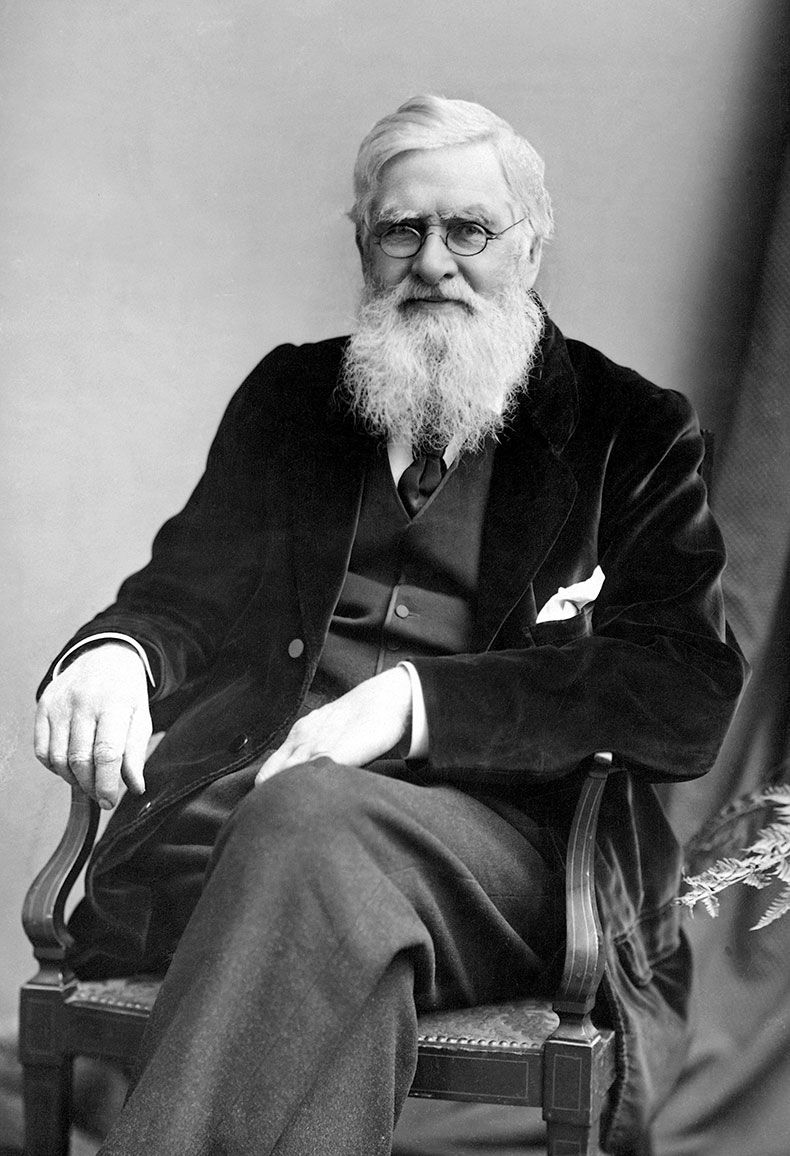

Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) had little formal education and no social connections. He knew that all official routes into the rarefied world of natural history, in which he hoped to work, were closed to him. So he did what any bright, ambitious adventurer would do: he took himself off to the Brazilian Amazon to collect tropical exotica. It proved a momentous move for the man who would later hit on the idea of evolution by natural selection prior to Charles Darwin’s public declaration of the same.

For four years, Wallace explored the banks of the Amazon and its tributaries, his finds from the virgin rainforests – many of them new to science – exciting huge interest among botanical collectors back home. In mid 1852, severely weakened by malaria and ready to cash in the fruits of his labour, material and intellectual, he booked himself a passage home. A month into the journey, disaster struck. A fire broke out in the hold, which, after the captain ordered the airless hold to be opened, burst into a full-scale conflagration. Soon, the aspiring natural scientist found himself bobbing up and down in a rickety lifeboat in the middle of the Atlantic.

Wallace would eventually make it home safely (a trading ship picked them up about 215 miles off Bermuda), but the considerable botanical collection that he had built up sank with the ship. All he salvaged was a ‘small tin box’ of shirts, into which he had thrown a watch, a purse of small change and a sheaf of drawings of palms and fish, which happened to be loose in his cabin. In the words of his latest biographer, James Costa, he had become ‘a collector without a collection’.

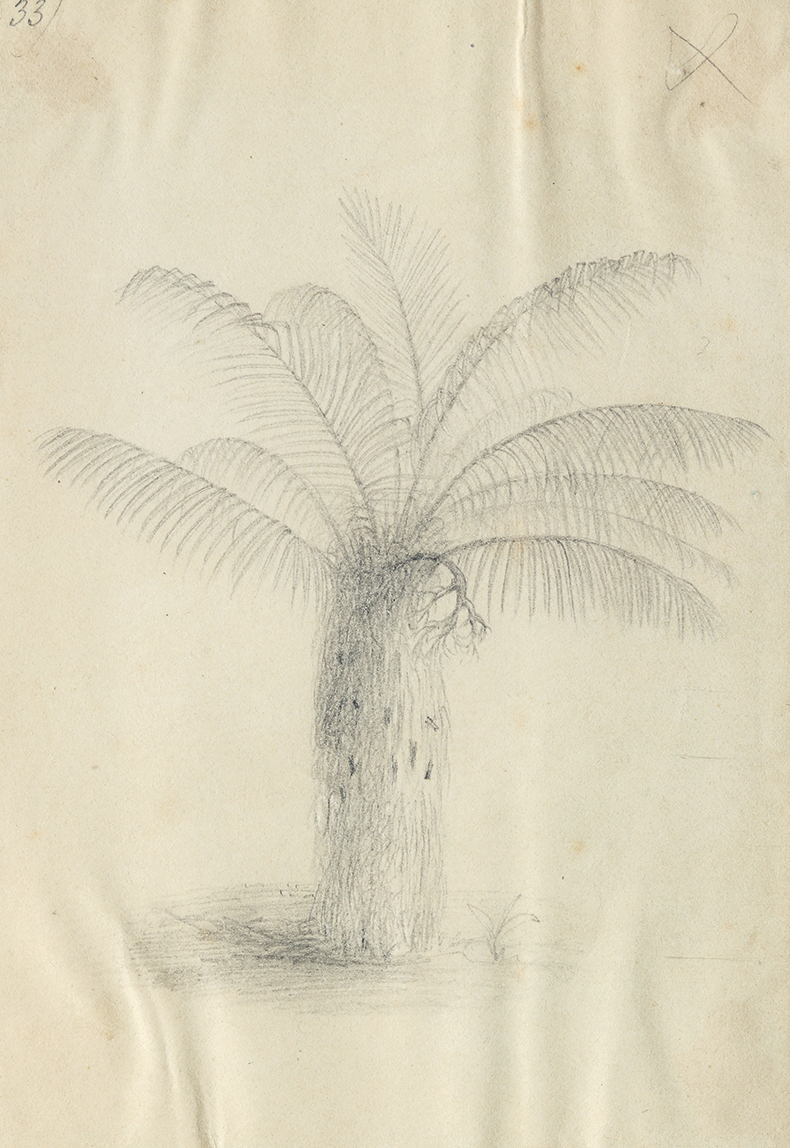

The randomly seized palm drawings, now held by the Linnean Society in London, offer a tantalising glimpse of what Wallace – and, by extension, the world of natural science – lost to the waves. The sketches show 48 different species of palm, four of them unnamed by science. Biologists took particular interest in the Leopoldinia piassaba, which, despite being extensively traded in Europe for use in brooms, was little known in its wild state.

A sketch of Leopoldinia piassaba from a notebook of c. 1848 on the palms of the Amazon by Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913). Linnean Society, London

As Wallace’s rough yet lifelike pencil sketch shows, its leaves, which grow to about four metres, stretch up and outward in a thick, interlacing crown. Bearded leaf sheaths coat the plant’s spherical trunk, leading to (loose) comparisons with a bear’s shaggy brown coat.

Far from falling into a funk, the irrepressible Wallace quickly established himself as a vocal presence in London’s scientific salons. Within a year, he had written impressive papers on the fauna of the Amazon – monkeys, butterflies and ‘some curious fishes allied to the Electric Eel’ – as well as a lengthy travelogue of his rainforest adventures. Bar a smattering of letters and articles written during his Brazilian sojourn, all of these works are products of Wallace’s formidable powers of memory.

The palm sketches are notable exceptions. He dutifully pasted these into a notebook together with extensive descriptions of each separate species. Of the piassaba, for example, we learn that its petioles are ‘slender and smooth’, its spadix ‘large, excessively branched and drooping’ and its fruit ‘globose and eatable’. Their scientific qualities aside, each draw- ing conveys a delightful tenderness. One can imagine Wallace, sat on the buttress roots of a giant kapok tree, sweat trickling down his neck, sandflies biting at his ankles, entirely absorbed in capturing on crude paper the beauties of a favourite palm.

This scrapbook-style creation was the basis for Wallace’s first book, Palm Trees of the Amazon and Their Uses (1853). With an initial print run of only 250 copies, it was never really conceived as a commercial enterprise – more a tribute to the ‘graceful Palms, true denizens of the tropics’ that had so captured his imagination. In the published version, the hand-drawn sketches are replaced with lithographs by the in-demand Scottish botanical illustrator Walter Hood Fitch. Faithfully copied and expertly executed as Fitch’s transpositions are, the stark assertiveness of the plate form loses the subtle affection that distinguishes the originals.

Photo: GL Archive/Alamy Stock Photo

Wallace’s palm book is also remarkable as a signpost for what was to come. Soon, the indefatigable naturalist was back on the high seas, this time bound for the Malay Archipelago and fame – albeit temporary – as Darwin’s competitor. Wallace was a geographer first and foremost, and his breakthrough as an evolutionist derives primarily from his observations about the geographic distribution of species. Geology, climate, hydrology: all, he came to see, play a role in the how, when and, above all, where of the evolutionary process. The precise data on location that litters his book on palms (a third of the chapter on the piassaba is spent on its distribution: ‘grows in swampy or partially flooded lands’, ‘on the banks of black-water rivers’, etc.) reveals the roots of such thinking in Amazonia.

Leading botanists were dismissive of Wallace’s short work on palms. Even his friend and fellow collector Richard Spruce dismissed Wallace’s descriptions of the trees as ‘worse than nothing, in many cases not mentioning a single circumstance that a botanist would most desire to know’. A case, clearly, of not seeing the wood for the trees. Spruce allowed himself at least one compliment: the pictures were, he agreed, ‘very pretty’.

From the April 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.