On the occasion of a major show at the Shed in New York, the conceptual artist Agnes Denes talks to Gabrielle Schwarz about what it meant to plant a wheatfield in Manhattan – and why she would need at least 500 years to complete all her unrealised projects

Your work across drawing, sculpture, and environmental installations incorporates ideas from many non-artistic fields – such as philosophy, mathematics, science. What first drove you to work in this way?

I wanted to involve all of life, to investigate its processes and put them into visual form. I wanted to evaluate all of human knowledge – which was quite a stupid, enormous task. But, of course, I went for it, as all young people do – they go for things that are impossible to achieve. I didn’t realise that it would take the rest of my life but I did achieve some milestones.

Were there particular figures who inspired you to follow this path?

Everybody asks that. Leonardo is the only one I can think of. There may have been others, but they were probably not artists. Many artists today are working in many fields and I don’t know where that originated from. Some people say it came from my work; I am not sure. People are beginning to realise that you cannot go in just one direction, unfortunately you have to go in many directions at the same time.

This is your largest institutional show so far in New York. Manhattan was also the site of one of your most influential works, Wheatfield – A Confrontation [1982], in which a wheatfield was planted on a landfill site at the foot of the World Trade Center. What was it like to create that piece?

Well, the land given to me was four acres of Manhattan. We only had money for two acres of it to be used, because I had only $10,000 to do that whole project – from the Public Art Fund – and so we only planted two acres, but four acres of Manhattan were mine for a summer. And then after I harvested the wheat, they continued building Battery Park City. So it became a city of condominiums, office space, and billions of dollars of business. And that is what Wheatfield was about. It’s about misuse of land, or abuse of space. Thinking of money instead of all the other things we should be thinking about. Like the end of world hunger, the end of so many things that I don’t need to voice because they’ve been voiced by many others.

At the end of the project, you created a time capsule containing surveys made up of ‘existential questions’, filled out mostly by university students. Why did you do this?

It’s communicating with the future. After each of my works, a time capsule is buried. Reactions to my questionnaire by all those involved around a project. I want the future to read us by the questions we asked and the answers we gave. I lament our short-lived existence, so I’m trying to overcome it, and communicating with the future is one way of doing that.

All my work is about doing something for humanity. It’s not just philosophy and visual beauty. My work, if you examine it carefully, is about dealing with problems humanity has and trying to find benign solutions.

Are you hopeful about the future of humanity?

A lot of people ask that question. I lament a lot of things about human life, about human nature. I worry about humanity’s underside, the bad thinking versus the good. I admire a lot of things about humanity, but I’m also aware of a lot of mistakes we are going to make. That might make me want to worry about the future. But I think we’ll make it.

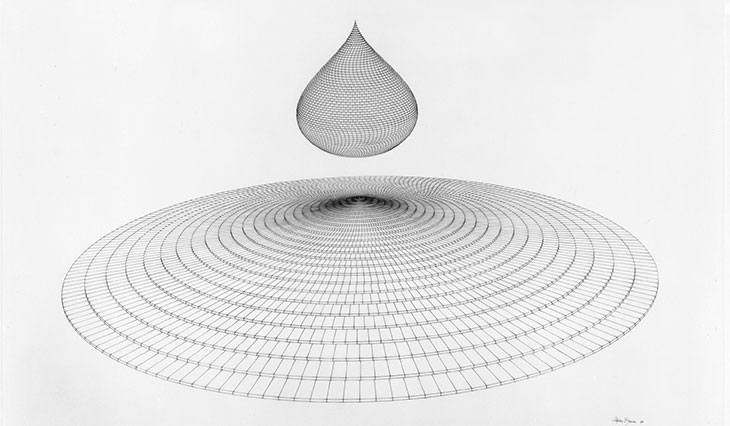

Teardrop – Monument to Being Earthbound (1984), Agnes Denes. Courtesy the artist and Leslie Tonkonow Artworks + Projects

The exhibition at the Shed includes unrealised projects, some of which have been made into three-dimensional models for the first time. Why did you want to include these?

I’ve had over 650 exhibitions – I don’t tell people what to exhibit. What they’re interested in is what is exhibited. There will be some of my forests that are not yet built – although I have one that is a 400-year project, which will create the first man-made virgin forest [Tree Mountain, 1992]. That will take 400 years to complete because the ecosystem takes about four centuries to rebuild itself and become a virgin forest.

But a lot of the projects remain unrealised, perhaps because I am a woman. And they would always realise a man’s project, even if it was half-thought-out. They would always prefer a man because they trusted a man more than they would trust a woman. And that is slowly, slowly, slowly changing. I’m not belabouring the fact, I’m not thinking ‘Okay, this was the only reason’ – but it was one main reason.

Is there a particular project you hope still to realise?

The ‘Future City’ project. ‘Future City’ deals with, among many other things, our problem with the weather. How to create structures that will withstand further flooding and drought and other disasters. And it creates individual structures that are self-contained, that grow their own food, have their own educational systems and are totally self-reliant. It will help us in the future. People will have to read about it and look at the images. That is a complicated project that I started working on in the mid 1980s and I understand it’s not easy to realise.

Once, when I was asked how much more time I would need to create my projects, without hesitating I said 500 years. And when I thought about it: what a silly answer, 500 years wouldn’t be enough. And it would be very boring to live that long. So we are limited in so many ways and I think, perhaps, that my art is about overcoming our limitations. Overcoming the limitations of being a human being, a philosopher, a creator, overcoming the limitations of the years given to live.

‘Agnes Denes: Absolutes and Intermediates’ is at the Shed, New York, until 22 March 2020.