A public body or institution decides it will embark on an ambitious building programme, perhaps a commemoration of an event in the nation’s history. It earmarks a sum of money from its apparently deep pockets and looks for a suitable project to finance. The idea gets off the ground, with its substantial dowry, but the ambitions of the enterprise quickly overstep reality: the architects start griping or over-reaching themselves, and the scheme soon sours. Sound familiar?

But this was 1818. To celebrate the recent end of the Napoleonic Wars, parliament passed the Act for Building New Churches, allocating £1 million for the task; the buildings that resulted were often known as the Waterloo churches. At the time, the church was in crisis, a situation brought about by changing demographics and altering religious affiliations: the surge of the working-class population in major cities, especially in the north, and the drift to nonconformity. The Church Building Commission (the predecessors of the Church Commissioners) turned to the government Board of Works, and its three advisory (and executive) architects, to set guidelines and advise on practicalities. Soon each was commissioned to design several churches.

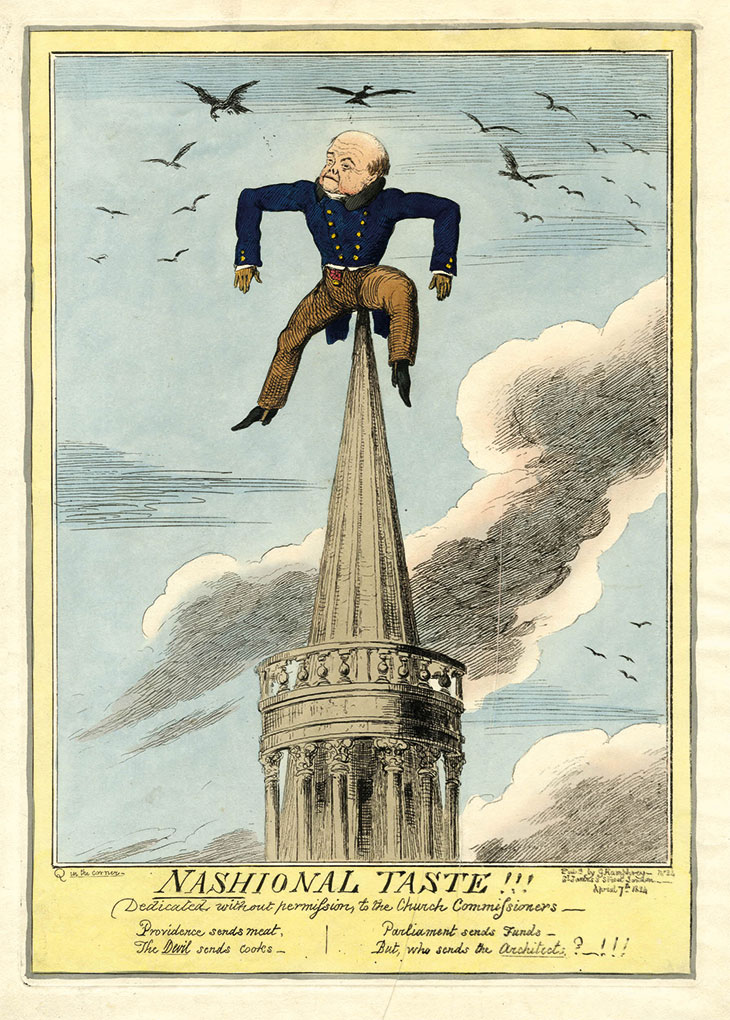

Nashional Taste!!! (depicting John Nash impaled on the spire of All Souls, Langham Place) (1824), George Cruikshank. Photo: © Trustees of the British Museum

John Nash (1752–1835), John Soane (1753–1837), and their junior, Robert Smirke (1780–1867) made uncomfortable colleagues – with very different approaches to expenditure, design, and even the established church. Smirke, who had not been happy working in Soane’s office, was now viewed by him as a professional adversary. The contrast in attitude between Smirke and Nash was caught in James Planché’s ditty of 1846: ‘Go to work, rival Smirke / Make a dash, à la Nash.’

But a previous programme, the churches built under Queen Anne’s Act of 1711, had set a high architectural precedent. By 1824 the budget had been increased, suggesting that the Commission’s ambitions were found wanting when tested against reality. The Hon. and Revd Gerald Valerian Wellesley, brother of the Duke of Wellington and rector at Chelsea, had been quick off the mark; with Chelsea Old Church too small for parish needs, he announced plans for a new church, St Luke’s, at a public meeting in 1818. James Savage designed an immense Georgian preaching box, and dressed it in gothic. It was fairly typical of what was to follow.

It should have come as no surprise to the Board of Works architects that quality would be compromised; the instruction had been unequivocal, to find a way of accommodating ‘the greatest number of persons at the smallest expense’. No church should cost more than £20,000. By the end of the Commission’s term, in 1856, some 600 new churches would stand across the country. But at the outset, the three architects approached their task differently; none of them had ever built a church, and Soane in particular was vociferously anti-clerical.

A Group of Churches, designed by Sir J. Soane to illustrate different Styles of Architecture (showing variant designs for the churches of Holy Trinity, Marylebone, St Peter’s, Walworth and the chapel at Tyringham, Buckinghamshire) (c. 1825), Joseph Michael Gandy. Courtesy Sir John Soane’s Museum

They began by producing alternative plans and estimates. Soane sensibly looked at a couple of existing models, both on a hall plan: St James’s, Piccadilly, which he reckoned would accommodate 2,800 and cost £23,500 to recreate, and Egham church in Surrey. He set his trusted perspectivist Joseph Gandy to work. Later, he produced several composite images of Soane’s churches, built or unbuilt, for exhibition, their elevations combining gothic and classical elements, with varied towers, cupolas and spires. Soane would not enjoy working as a church architect in the 1820s, faced with the difficulties of putting work out to tender and staying within unduly tight budgets. But at this early stage, he decided to relax and enjoy himself. Nash took a more frivolous approach, designing many options, with scant attention to budget. The 10 wildly varied alternatives he offered gave the impression, as John Summerson laconically wrote, ‘that anyone in the office was allowed to have a go’.

After the trial runs, the three architects were invited to start designing some of the churches. Only Smirke ventured outside London, designing four of his seven further afield, in Bristol, Salford, Chatham and Tyldesley (his only gothic effort). Nash designed just two: St Mary’s, Haggerston (destroyed by bombing in the Second World War) and All Souls, Langham Place. The first was fronted with a spindly, pinnacled tower topped with a miniature version of itself, like a Gothic Revival Russian doll. It had all Nash’s brio – and even cost less than the limit, at £15,153 – and must have been a strong symbol of the revived church in the Hackney of the 1820s. All Souls was a design of completely different quality, crucially linked to Nash’s great route through central London to Regent’s Park. The church became a hinge-point, a brilliant shift on plan, pivoting the vestibule and creating an eye-catcher on Langham Place. All Souls is still a well-used church; it even offers the option of downloading sermons as podcasts, perhaps thanks to its location next to Broadcasting House.

St Mary’s Church, Haggerston (showing the church designed by John Nash and constructed in 1827) (1827), Robert Blemmell Schnebbelie. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum

Soane’s three churches were all in London and tend to be dismissed quickly in discussions of his work. The most intact is St Peter’s, Walworth; in Ptolemy Dean’s view, it ‘deserves a kinder press’. It has touches of Soane’s characteristic detailing, such as the shallow blank arches he had already used on the stables at the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, and at Dulwich Picture Gallery, giving depth and articulation to the long side walls of a hall built to accommodate 2,000 people. The main flourish – a strong statement when glimpsed from the Walworth Road – is a handsome Ionic portico with a soaring stone tower above. Soane chose Bath stone, more economic than Portland stone, and slate in preference to lead roofing. Even with his best economies, he had to plead with the Commissioners to increase the budget of £16,000. The church has seen many changes locally; it was later within the Church Commissioners’ largest London housing estate, managed by Octavia Hill, and remains active and engaged with community needs.

Soane’s Holy Trinity, Marylebone has followed a very different path. Always overshadowed by Thomas Hardwick’s neighbouring Marylebone Parish Church of 1817, which cost a splendid £80,000, it was used to store books from the 1930s onwards, first by Penguin and then, until 2006, by the Society for the Promoting of Christian Knowledge. Afterwards it emerged, ‘refurbished to the original designs of John Soane’ as a party venue, its road frontage illuminated by mauve light and lit with flambeaux. One Marylebone, as it is now called, is a long way from Holy Trinity. The third of Soane’s churches, St John’s, Bethnal Green, was severely damaged by fire in 1870 and retains little more than a shell of his design. Like St Peter’s it is an active church – and one that now also has a diverse music programme. Perhaps the requirement of 1818, to build big halls for the crowds of new churchgoers, was to be the saving of these buildings 200 years later.

From the June 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.