Since 1975, New Yorkers have been able to experience various iterations of the Thaw Collection of drawings in exhibitions at the Morgan Library & Museum. The sixth – widely acclaimed – closed last month; it will now travel to the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, only the fourth time that Thaw’s drawings have been exhibited outside Manhattan (3 February–22 April). If you missed it in New York City, make every effort to see the show there: at both venues it includes 150 sheets, selected from more than 400 drawings collected by Thaw over the past five decades. Slight changes to the checklist have been necessary for the second venue, to minimise the exposure of some works to light. While individual drawings by Palmer, Turner, Seurat, and Van Gogh will not travel north, the Clark presentation benefits from the addition of three sketch books by Cézanne, Degas, and Pollock. All works exhibited at the two venues are published in the excellent exhibition catalogue.

Eugene Thaw (1927–2018), who died the week before the Morgan exhibition closed, was not only a committed and astute collector, but also an art dealer known for handling Old Masters and modern and contemporary works of exceptional quality. Along with his wife, Clare, he was committed to building significant groupings of drawings by his favourite artists rather than seeking to collect the works of a particular school or epoch, preferring the pictorial over the historical. Time spent studying with Meyer Schapiro and Millard Meiss at Columbia University, friendships with mentors such as Pierre Matisse and Janos Scholz, and associations with Leo Castelli and Sidney Janis helped him formulate his philosophy of collecting, as did his own curiosity, passion, and discipline. ‘Each collection,’ he said, ‘achieves a personality beyond and apart from the sum of the objects […] and this personality is lost if the collection is dispersed or mutilated.’

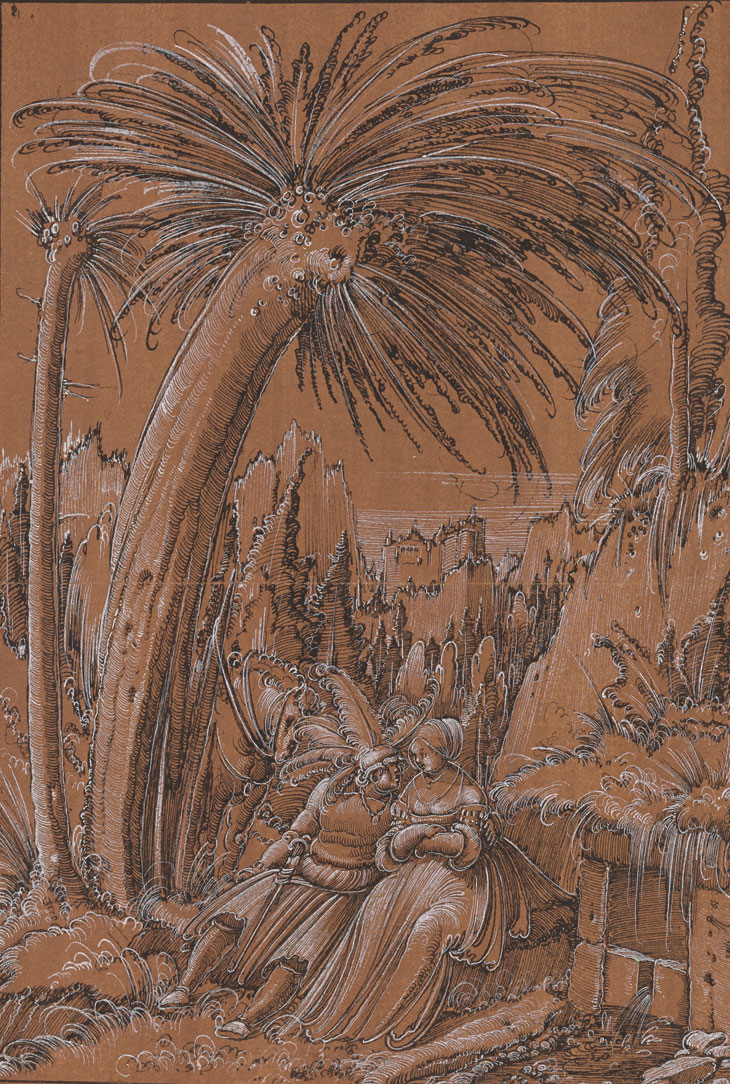

Two Lovers by a Fountain in a Landscape (c. 1509–10), Albrecht Altdorfer. Thaw Collection, Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Fortunately Thaw followed his own advice, keeping this collection, and its personality, intact; it is particularly strong in the area of autonomous drawings from the 15th to the 20th centuries, which provides a connecting thread through the broad chronological and thematic arrangement of the exhibition. Albrecht Altdorfer’s Two Lovers by a Fountain in a Landscape (c. 1509–10), drawn with pen and black ink, with white opaque watercolour on coloured ground, is but one fitting example; it was surely intended for the growing cadre of collectors in the 16th century.

Few exhibitions can adequately cover the breadth of European drawing over five centuries based on the holdings of a single collection. Thaw’s drawings can be divided up into groupings that mirror the shifts in artistic intentions that underscored them. Early in the 15th century, artists gradually began to treat drawing as an intellectual pursuit rather than simply a means to record things. Visualisation on paper or vellum became the handmaiden of invention. Artists began to adapt their drawing skills to match their keen analysis of literary sources, as Domenico Campagnola did with his Scene with Fallen Buildings: The Seventh Vial of the Apocalypse (c. 1545–50).

With the notion of invention added to the copying of motifs and observation of reality, artists increasingly needed to learn how to render their ideas. Academic programmes appeared in Florence and Rome, and soon afterwards in major art centres across Europe, aimed at teaching artists to create idealised forms based on a system that in time became codified. This method of instruction was intended to create works that could communicate forcefully and clearly: artists would begin by learning how to draw by copying plaster casts of ancient statues and reliefs, then advance to life studies, and lastly to adapting their academic drawings from stock motifs – as with the Female Nude (c. 1810) by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon in the Thaw Collection – into compositional arrangements illustrative of literary narratives.

To be sure, there were additional discussions about colour, the affetti, and countless other nuances that would constitute a successful work of art. But Thaw’s collection moves away from this material, reflecting his predilection for works by artists who rejected the classical style, and the strictures of the academy, and who generally resolved to draw how and what they wished. David’s Study for Execution of the Sons of Brutus (c. 1785), in which only Brutus and Publius Valerius are given a degree of finish, swerves from academic conventions as much as the unfinished arm of Prud’hon’s nude.

Three Studies for a Descent from the Cross (c. 1654), Rembrandt van Rijn. Thaw Collection, Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Indeed, Thaw preferred expression over academic correctness, seeking out works by figures such as the artist-cum-dramaturge Rembrandt, who treats the Three Studies for a Descent from the Cross (c. 1654) with utmost empathy. He also favoured artists who preferred to follow their own proclivities, who expressed the personal or unusual through flashes of genius on the sheet. There shouldn’t be any wonder, then, that Thaw was enticed by the technical brilliance of coloured chalks by Barocci or Watteau, or by Claude’s sensitive touches using sepia ink with pen and washes. Other drawings – in fact many in this collection – provide examples of unorthodox methods: with Castiglione, blurring the boundaries of painting and drawing by using oil paints on unprimed paper for his Allegory with a Courtier and a River God (late 1640s); in Friedrich’s Moonlit Landscape (before 1808), in which he cut out the moon and replaced that section of the watercolour with blank paper; in Redon’s shades of black chalks, erased, sprayed with fixatives and reworked; in Klee’s oil transfer drawing.

Thaw also gravitated towards works by artists who explored new subject matter – whether social issues, political upheaval, or simply their own internal musings. Hence the collection includes drawings that address philosophy, political and social history, and religion in myriad ways: from works by Goya, who produced biting, but poetic commentary on the social mores of Spanish society, to those by Ingres, who drew gem-like portraits with incredible verisimilitude because his patrons in Rome and Paris revered flawless semblance.

Seated Dancer (1871–72), Edgar Degas. Thaw Collection, Morgan Library & Museum, New York

Towards the end of the 19th century, those artists who turned to themes inspired by the deepest recesses of the mind often used unconventional means of representation, another vein that Thaw found appealing: think of Victor Hugo creating pen and wash drawings by pouring ink on to the paper, then dredging through the puddle with his nib to create an imaginary whatever. Nor was Thaw indifferent to artists who mixed stylistic approaches, as with Gauguin in The Queen (Te arii vahine) (1896–97), drawn with pastel and charcoal with watercolour and opaque watercolour, or Degas working oil paint over graphite on pink paper in his Seated Dancer (1871–72). Then there are stunning works from the 20th century, in which artists adapted a new vocabulary of forms, as with Jackson Pollock’s fusion of primitivism and modernism in his Untitled [Drawing for P.G.] (c. 1943). And there is far more besides, in an exhibition that offers visitors an extraordinarily rich experience. But you get the picture: make plans to head to Williamstown.

Untitled [Drawing for P.G.] (c. 1943), Jackson Pollock. Thaw Collection, Morgan Library & Museum, New York. © 2017 The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

![Untitled [Drawing for P.G.] (c. 1943), Jackson Pollock. Thaw Collection, Morgan Library & Museum, New York](http://new-dev.apollo-magazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Pollock_Untitled_Drawing-for-PG.jpg?resize=730%2C554)

‘Drawn to Greatness: Master Drawings from the Thaw Collection’ was at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York from 29 September 2017 to 7 February. The exhibition is at the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, until 22 April.

From the February issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.