August, I point out every year, is a blight on London’s artistic calendar – and most of the gallery world stays true to tedious form this summer. There is however one new exhibition that should not be missed, and may even merit repeat visits: the Royal Academy’s fascinating ‘Matisse in the Studio’ (until 12 November).

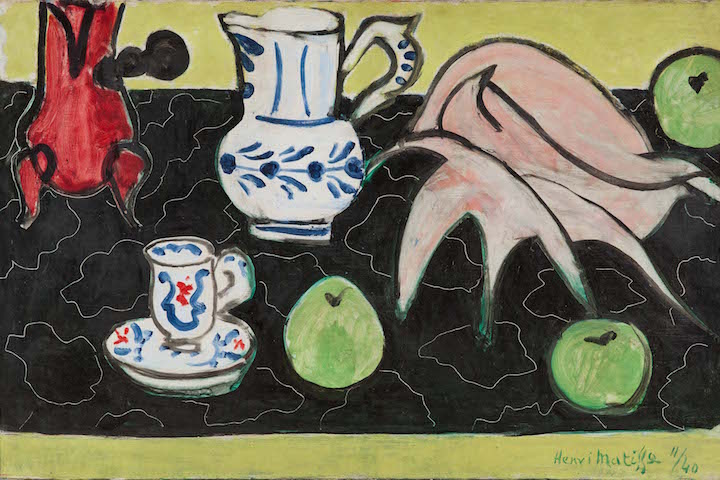

The idea to display studio props alongside the works in which they appear doesn’t sound all that thrilling, but in this case it works on every level. Matisse was a diligent hoarder of objects and artefacts, which he amassed for the beauty of their form alone. He ‘loved stuff’, as one critic put it – from Roman statues, to masks from the Congo Basin, and the squat little pot he used to brew his drinking chocolate.

Naturally, a lot of this ‘stuff’ ended up in his pictures. The chocolate pot appears in a diverse range of paintings created by the artist over the best part of half a century. A large wooden block bearing Chinese pictograms is set alongside the joyous cut-outs of dancing figures from his final years, its calligraphic designs seeming to whirl to the same rhythm. You could argue that Matisse’s magpie tastes amounted to cultural appropriation: in fact, the RA itself has invited speakers to debate the issue next month. In any case, this is a gorgeous display that gives genuine insight into how and why Matisse worked as he did.

Silver cafetière (early 19th century). Musée Matisse Nice

*

‘It is impossible to reconcile the art of Alma-Tadema with that of Matisse, Gauguin and Picasso’, the painter John Collier once wrote. Nevertheless, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, whose peculiar career is the subject of an exhibition at the Leighton House Museum (until 29 October), shared Matisse’s loyalty to props. A distinctive tiger-skin rug recurs in a surprising number of the works here, and – perhaps it’s just me – seems to become slightly more worn as the years go by. Before visiting, I knew of the artist as a purveyor of Victorian kitsch. While I wasn’t entirely wrong, the show makes an admirable effort to restore his reputation.

The exhibition covers Alma-Tadema’s entire career, from his cod-medieval juvenilia to his final, uncompleted historical scene, and it focuses appropriately on the artist’s domestic situation. Lord Leighton’s house is a space so over the top it was used as a location for Terry Gilliam’s Brazil: Alma-Tadema likewise created a palace of a home for himself and his sumptuous art, and devoted much of his later life to painting it. It’s exciting to feel as though, by looking at an artist’s work, you are trespassing on their property. This is a nosey parker’s paradise.

Self-Portrait of Lourens Alma Tadema (1852), Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. © Fries Museum, Collection Royal Frisian Society

*

What August is good for, if you’re stuck here, is long walks through the city. The other day, while zigzagging through the back alleys around Fleet Street, I found myself at Christopher Wren’s St Bride’s. The church has a museum in its crypt, which itself was only discovered after a German bombing raid all but destroyed the floor. As with so many small museums, it’s a space that could use a bit more funding. But do go – it’s full of the sort of parochial but hypnotic information about the area that would never make it into a larger institution. A sample, taken from a cutting of the Morning Herald on 1 July 1830:

‘Yesterday, a decently dressed man, who gave his name George Gunn, was charged with disturbing the congregation at St Bride’s church on Sunday morning last, by snoring so loudly as to prevent all those who happened to be near him from hearing a single word that was uttered by the minister. [The defendant entered the church] in a state of intoxication, and placed himself on a seat that was only calculated to accommodate two persons, and was already occupied by that number. […] He began to snore in the loudest and least harmonious manner possible, so as to distract the attention of all around him [and] at length the evil reached such a height that the minister was compelled to remove him and take him to the watch house.’

Mr Gunn, heavy sleepers among you will be pleased to note, was subsequently discharged with a rap on the knuckles.