On a grey day at the very end of November 2017, the Vervoordt company unveiled Kanaal, the latest instalment in the family business’s almost 50-year history. The company had bought the collection of impressive but derelict 19th-century brick industrial buildings, a former malting distillery, on the banks of the Albert Canal just outside Antwerp in 1998, moving in part of the firm a year later. But its founder, the influential interior designer, property developer and art dealer Axel Vervoordt, always had another vision for the site. Nearly 20 years later, this ‘lost corner of the world’, as Boris Vervoordt puts it, has been reconfigured as the flagship centre of what has become a global empire. An intertwined residential, commercial and cultural district, it is a concrete, brick and glass expression of Axel Vervoordt’s much admired aesthetic, with its love of humble, industrial materials. It is also a testament to his ideas about the central place of art from across centuries and cultures in life. Boris Vervoordt says, ‘To express this grand scale in a new build, in a city centre, would be very pretentious. We are entitled to do grand things here because this land was a wasteland.’

What attracts you first is the range of arresting geometries: the cylindrical silos preserved alongside red brick rectilinear warehouses with 19th-century Gothic windows, set against the new clean, white cuboid apartment blocks. There are now 98 apartments, 30 offices and supporting facilities, and a multi-use auditorium, alongside the Vervoordt company’s offices, workshops and restoration facilities, showrooms and exhibition spaces. The entire site is landscaped to bring nature into the community. Vehicles are hidden in underground car parks. There are upmarket food emporia: a branch of French artisan bakery, Poilâne, and an organic, fresh meat, cheese and vegetable market by Cru, as well as a restaurant. As Boris Vervoordt remarked in his opening address to the press, ‘We are not functioning like any other gallery or any other dealers.’

There is, however, art in abundance. Multiple new spaces for its display have been designed by Axel Vervoordt in collaboration with the architect Tatsuro Miki, according to the Japanese ‘Wabi-sabi’ principles they share. The majority of the art on show is owned by the Axel and May Vervoordt Foundation. A former chapel, entered in darkness, is now home to an intensely glowing, red light installation by James Turrell: a deconsecrated space reconsecrated to art. A warehouse space has been reconfigured to house Anish Kapoor’s large red dome sculpture At the Edge of the World, first installed in 2000 and offering a similarly immersive experience. A cluster of silos has been kept intact to offer darkened spaces akin to Tate Modern’s Tanks for the display of video installations and sculpture by Tatsuo Miyajima, Marina Abramović, and others. A chilly ground-floor area filled with cylindrical concrete pillars, located beneath the gleaming glass box that homes the new Vervoordt Company offices, has become a temple-like space for the foundation’s collection of Thai Buddhist sculpture from the Dvaravati and later periods.

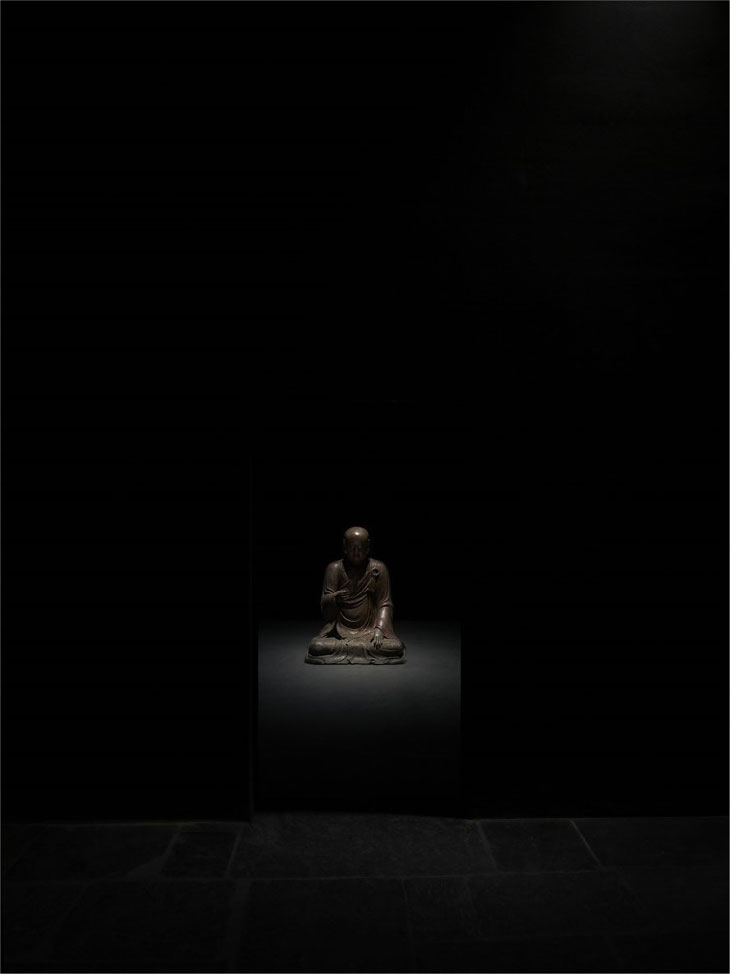

Seated Lohan (960–1127 AD), installation view in Henro I Gallery. Photo: Laziz Hamani courtesy of Axel & May Vervoordt Foundation

At the heart of Kanaal is the largest newly-converted warehouse, its industrial surfaces and dimensions left intact. Inaugurating this space, Miki and Vervoordt have created a semi-permanent display of works from the collection, presented in a labyrinth of pitch-black rooms (for which visitors need to book a guided tour). An Ancient Egyptian sculpture, brightly lit, is displayed alongside a 1560 Japanese painting and a contemporary gunpowder painting by Cai Guo-Qiang, showing off Vervoordt’s trademark flare for bold juxtaposition. Works by Vervoordt favourites – Zero artists Günther Uecker, Otto Piene, and Heinz Mack; Gutai participants Yoshihara Jiro, Shiraga Kazuo and Shozo Shimamoto – are placed in dialogue, while one room, constructed according to the golden ratio, houses a single Song Dynasty sculpture of a monk. This is as much dramaturgy as design, constructing an intimate and powerful experience for each visitor.

Lucia Bru, installation view at Escher Gallery © Jan Liégeois

Alongside these collection displays are the commercial spaces. The floor above Axel Vervoordt’s maze, with its wide windows facing the canal, exhibits rare large-scale works by the Gutai artist Murakami Saburo (until 17 March). The Terrace gallery, as it has been named, will be dedicated to the secondary market. Another space wedged at right angles to the main building, the Patio gallery, will present solo shows of leading contemporary artists; the inaugural offering consisted of gleaming wall-panels by El Anatsui, and next week will open a new exhibition of paintings by Raimund Girke. Back at the main entrance to the complex, a third gallery – called the Escher after the central concrete staircase and strange holes in the ceiling, left behind by dismantled malt boilers – will be devoted to more experimental work, such as the next show with South Korean video and installation artist Kimsooja.

There is no doubting the conviction with which this settlement has been conjured from abandoned ground. Already the company has sold 90 of the 98 apartments in its residential quarters. And as fairs rather than city galleries become the principle fora for art-dealing, Kanaal makes the case for the appeal of a seductive, immersive haven rather than a place for the hard sell.