From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

It feels like a long time that we’ve been without the Studio Museum in Harlem. Founded to address the lack of New York City institutions dedicated to art created by members of the African diaspora, it has been missed these past seven years. It’s true that Black artists have recently achieved a presence that could have only been imagined at the time of the museum’s creation. While it was closed, artists whose careers were launched at the Studio Museum, such as Kerry James Marshall and Julie Mehretu, set records at auction. The role of the Studio Museum, however, has been not only to sustain Black artistic production but also to challenge easy definitions and demarcations of ‘Black’ art – by the art market or elsewhere – by expanding our sense of the themes, topics and audiences it addresses.

Finally, after delays caused by the pandemic and unforeseen issues with the site, the museum will reopen this month, for the first time in a splendid, purpose-built new home. The new building was funded by a capital campaign that raised more than $300 million (almost double the initial estimate) from individuals, foundations and corporate sponsors, and from the City of New York. As the museum prepares to enter a new era, its director and chief curator, Thelma Golden, is determined to hold its history close. ‘I see our building project as an inflection point, one that lets us honour the past and allows that past to inform how we talk about the museum now and how we think about the institution’s future.’

Established in September 1968, the Studio Museum has no single founder. Neither a monument to a wealthy donor nor a storehouse for a prestigious collection, it reflects instead a moment of art world organising. During the ’60s, activists across New York called for Black leadership at arts institutions, fought to have the work of Black artists displayed in museums and galleries and founded their own organisations and institutions when the mainstream art world fell short. Between the Civil Rights and Black Power movements and amid progress and reaction – in the same year a federal ban on housing discrimination was passed and Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated – a group of artists, activists, educators and business leaders saw a need and moved to address it. They founded an everyday museum, a museum in and of its community. Their goal was not only to show work by artists of African descent but also to help bring that work into being. From the start, a residency programme put the ‘studio’ in the museum, providing artists with funding and a space to work in Harlem, a global capital of Black culture. Young community members worked with the artists-in-residence as apprentices or trained in the museum’s film unit.

The Studio Museum first opened in a rented second-floor space on a mixed-use block, above a liquor store and a beauty salon. When it moved in 1982, it was to a new site a few blocks away, a former bank that had also seen life as a furniture store. Renovations in the 1980s and ’90s updated the building, although its capacities remained limited. Galleries were cramped, but the intimacy of the space wasn’t always a drawback; events felt like well-attended house parties. The museum’s expanding mission, however, clearly required more. Golden sees the new space as both a return and a new beginning. ‘The museum exists in the same place, as we move back into 144 West 125th Street,’ she says, ‘but it is wholly new, with an entirely new physical space.’

Adjaye Associates, which also designed the National Museum of African American History and Culture, has created a striking open facade, a cluster of stacked frames, windows and doors in dark grey concrete. Visitors enter a lofty interior, the heights of which are punctuated by the rhythmic geometric forms of an ascending staircase, clad in black terrazzo, and the descending ‘reverse stoop’ – a massive set of steps in warm wood dropping away from the front doors. The stoop and its adjoining ground-level cafe, both free to enter, reflect an institutional desire to dissolve the barriers between the museum and the life of the street.

The galleries, studios and other spaces wrap around a central light well, with the compact, vertical design and efficient ordering of space recalling the kinds of buildings New Yorkers call home. The overall design is inspired by the built environment of Harlem and its bustling indoor and outdoor spaces. First, there’s the street. Unlike the art museums in the quiet preserves of the Upper East Side – the Met, perched atop four metres of stairs, or the Guggenheim, hovering over Central Park – the Studio Museum nestles in the middle of its Harlem block, where vendors make their living and where people congregate at all hours. Then there’s sanctuary. In the galleries, floor-to-ceiling windows look on to the steeples of Harlem’s many churches, spaces of spiritual solace and social action. Finally, the stage, an acknowledgement of the central place of the performing arts in Black culture and of historic Harlem venues such as the nearby Apollo Theater, is created in the doubling of the ‘reverse stoop’ as performance space.

What constitutes ‘Black’ art? What does it mean to show Black culture and where should it be seen? The museum has been shaped by these difficult debates – and continues to shape them today. The group who founded the Studio Museum, several of whom held roles at MoMA and the Met, initially envisioned it as a meeting place for New York’s Black and white art worlds. Local, Black-led cultural organisations such as the Harlem Cultural Council felt that Harlem needed investment in local initiatives more than it needed a mainstream museum attracting downtowners. They were rightly wary of institutional encroachment – Columbia University had recently tried to build a gymnasium on public land in a Harlem park – and concerned that the new museum would do nothing for the neighbourhood’s many artists. Debates extended to the work on view, with proponents of Afrocentric, politically informed art arguing that the museum’s commitment to showing abstract and formally experimental work amounted to an abdication of its responsibility to inspire social change.

These early challenges prompted a decisive turn towards the Harlem community, led by the museum’s second director, Edward S. Spriggs, who took over from Charles Inniss in 1969. Debates over the themes and topics the muse um should address have informed an exhibition programme that emphasises complexity, diversity and differences of opinion within Black art and culture. Although in 1977 a name change (to the Museum of African American Art) was contemplated, along with a move that would place the institution closer to New York’s other art museums, the Studio Museum has held on to a vision that encompasses both the global and the local, with programmes and exhibitions that explore the whole of the African diaspora and the cultural and historical specificity of its immediate community in Harlem.

In 1969 alone, the museum’s exhibitions introduced the public to contemporary Haitian art, showed photography documenting the activism of the Black Panthers, explored contemporary abstraction and presented work by Harlem artists. Studio Museum shows have decisively changed the terrain in the art world, first by making race and identity a concern, then by challenging their power to shape meaning. The museum broke new ground in 1990 with ‘The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s’. Organised with the New Museum and the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, the exhibition was one of the first ever to take identity – not only race, but also gender and sexuality – as an organising principle.

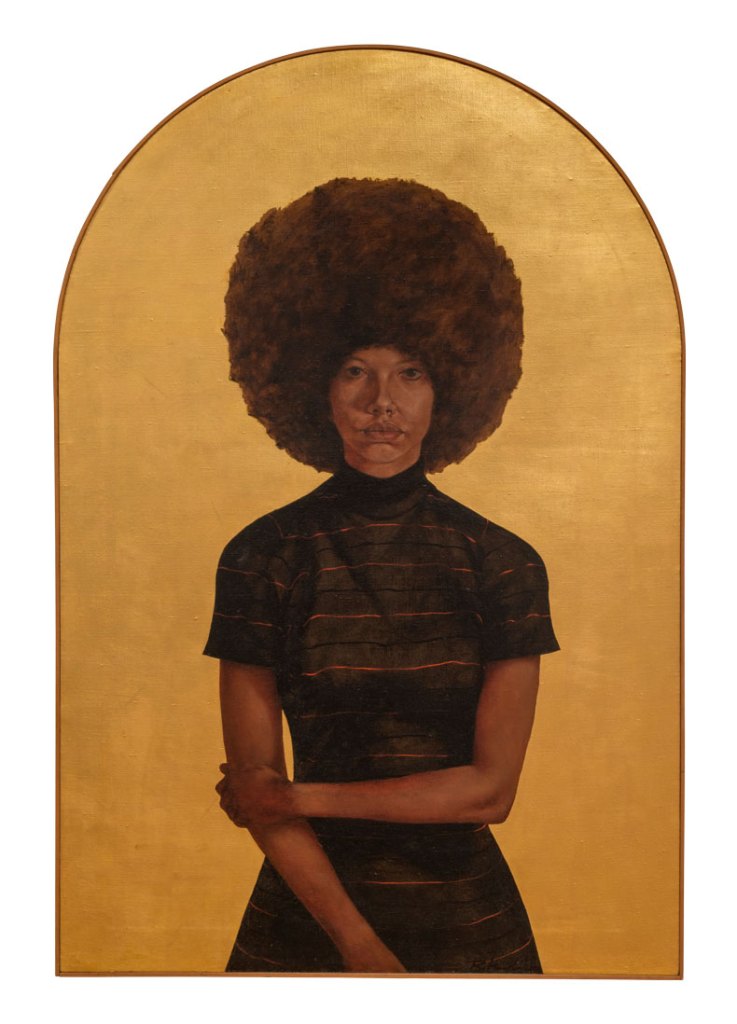

Under the leadership of Golden, who arrived at the museum as deputy director for exhibitions in 2000 and became director and chief curator in 2005, the Studio Museum rolled out the exhibitions known as the ‘F’ shows. In 2001, the first, ‘Freestyle’, revealed artists who were questioning the place and meaning of Blackness in their work. It yielded the famous, partly tongue-in-cheek, partly serious coinage ‘post-black’, which Golden and the artist Glenn Ligon used to name those artists who refused to be defined by the category, yet whose lives and careers were indisputably shaped by its existence. In the New York Times, Holland Cotter wrote that the show’s best artists, ‘along with the young curators, scholars and critics who contribute to its slender but spicy catalogue – are operating beyond the level of conceptual noodling that seems to be endemic at present. They’re actually talking about something – life – and we’re sure to be hearing from many of them again soon.’ Next came ‘Frequency’, ‘Flow’ (focusing on artists born in Africa working in Europe or the United States), ‘Fore’, and finally, in 2017, ‘Fictions’. These shows presented formally and materially experimental new work reflecting on Black and African identity by artists including Hank Willis Thomas, Thierry Fontaine, Toyin Ojih Odutola and Sable Elyse Smith.

When the Studio Museum reopens, the main gallery will hold an exhibition dedicated to the sculptor Tom Lloyd (1929–96). The Studio Museum’s Artist-in-Residence programme has hosted some of most prominent artists working today – Simone Leigh, Kerry James Marshall and Mickalene Thomas, to name just a few. It would be easy to imagine the new building opening with a show organised around one or more of these names. But that’s not the Studio Museum’s game. When I asked curator Connie Choi about the choice to focus on Lloyd, who is something of an unknown, she spoke of the museum’s mission. ‘The Studio Museum was founded with a deep understanding of what it meant to be a new institution that could contribute something different to the artistic landscape of New York, one that was willing to take risks by supporting work that was experimental, work that was utilising new technologies and new mediums. Throughout our founding documents you see […] a deep commitment to artists who weren’t getting institutional support, not only because they were Black, but because the work that they were making was not painting or sculpture.’

Lloyd holds a special place in the institution’s history. He was the museum’s first artist-in-residence and the first artist to have a solo exhibition at the museum. An artist, educator and community organiser, he founded the Store Front Museum in Jamaica, Queens, which between 1971 and 1988 celebrated Black art and culture through exhibitions, performance, festivals and programmes.

As an artist, his medium was light. Long before art and technology seemed a natural pairing, he worked with Alan Sussman, an engineer at Radio Corporation of America (RCA), to create electronic abstractions. The bold geometric shapes of his wall-mounted sculptures, like street lights from another planet, pulse with prismatic colour. Arranged behind lenses that blur and amplify their luminosity, modular arrays of multi-coloured bulbs flash in programmed sequences. Their extended patterns feel like communication; if we took enough time to grasp their rhythm and repetition, a message might be revealed. Until MoMA acquired a light sculpture called Veleuro in 2024, Lloyd’s work was held only by university collections. Because of the deterioration of the technological materials Lloyd used and the difficulty of replacing obsolescent and damaged components, it was rarely displayed. (The Studio Museum show has prompted an extensive and meticulous programme of conservation.)

The Studio Museum’s commitment to experimental artists like Lloyd has not gone unchallenged. When his first exhibition opened in 1968, the museum received criticism for displaying work that seemed abstracted from the social and material issues facing the Black community. Spriggs, writing in 2011, reflected on the gulf that seemed to separate Lloyd’s work from the community. ‘Harlem had spoken and was saying that you cannot just bring anything you want to Harlem and press it on us anymore.’ To some minds, Lloyd’s art simply did not seem Black enough.

In 1969 Lloyd took part in a symposium convened by the Met to address the fallout after the failure of its ‘Harlem on My Mind’ exhibition to include the work of a single living Black artist. Lloyd, Jacob Lawrence, Hale Woodruff and other artists came together, in a discussion moderated by Romare Bearden, to talk about the situation facing Black artists in America. When it was suggested that Lloyd’s work, rather than reflecting the Black experience, was created by an artist who simply ‘happens to be black’, Lloyd insisted that his identity was inseparable from his art. For Lloyd, and perhaps for the Studio Museum too, Black art is a space of boundless possibility. ‘Black art can be any kind of art, it can be anything,’ said Lloyd. ‘It can be a painting of a little black child or a laser beam running around the room.’

The Studio Museum will also inaugurate its new building with a rotating display of work from the permanent collection. This is another first. The smaller galleries of the old building meant that visitors rarely had the chance to experience the scope and scale of the collection. Now the museum has 1,300 square metres of gallery space, an increase of more than 50 per cent. The majority of the 9,000 works in the collection were created from the mid 20th century onwards, but there are also earlier works, by the artists working in and around the Harlem Renaissance – and even earlier: Joshua Johnson’s Portrait of Sarah Maria Coward (c. 1804), for instance, and a landscape of 1878 by Edward Mitchell Bannister. ‘Rather than trying to create a linear chronological narrative,’ Choi says, ‘we want to demonstrate how the artists in our collection have reflected on the generations of artists who came before them and really make our audiences aware that these deep conversations are still happening today.’ While the museum has been closed, there have been gifts and acquisitions of work by more than 100 artists not previously represented. In 2021 the museum announced that, in collaboration with the Met, it would take over stewardship of the vast archive of the photographer James Van Der Zee, who captured the likenesses of Harlem residents, politicians and celebrities during the Harlem Renaissance.

In its early years the museum preferred to direct its limited funds to supporting artists directly, rather than acquiring and caring for a collection. Works of art came in nevertheless, as artists recognised the importance of their works being in a museum at a time when most major institutions had yet to acquire work by Black artists. That notion of stewardship is at the heart of the Studio Museum’s mission. ‘It’s the way we’ve understood that our work is not just what happens on the walls or inside the institution,’ Golden says. ‘It’s the way we hold and care for the ideas, and perhaps also the ideals, of artists of African descent. Institutionally, this has meant that the museum has existed in a space of preservation and presentation, but also very importantly, in a space of advocacy […] The work that the Studio Museum has done throughout has changed art history.’

The residency programme operates on the same principles. Credited to the abstract painter William T. Williams, one of the Studio Museum’s founders, the programme provides early career artists with studio space at the museum, financial support and a culminating exhibition and publication. Few museums can claim to have done as much to support the making of art, to have shown the foresight and the daring to trust artists rather than waiting for the market to shape their careers. From the programme, a close-knit community of artists with deep ties to the museum has emerged. Alumni supported the building project’s capital campaign by contributing work to a benefit auction – a collaged painting by Njideka Akunyili Crosby, who joined the museum as a resident artist in 2011, brought in $3.3 million of the $20.2 million raised in total. When the new building opens, more than 100 alumni will be represented in an exhibition of new works on paper, reflections on the time they spent at the museum.

A great deal has changed in Harlem since the Studio Museum closed its doors in 2018. Residents and local businesses have been priced out as chain stores such as Whole Foods move in. The Studio Museum, along with nearby institutions like the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which celebrates its centenary this year, preserve a history and a culture in danger of displacement.

Black artists, too, find themselves in a different place. We’ve come a long way since the exclusions of the ’60s. The art world in recent years has celebrated the work of Black artists in the form of major museum and gallery exhibitions and market success. Yet the current wave of reaction and the second Trump administration’s attacks on non-white people and identities, and on museums, arts funding and Black history, reveal the fragility of recent gains and the vulnerability of art and culture. Institutions can help us weather this instability.

As Golden says, ‘To be an institution that stewards Black art and culture means that we dedicate ourselves not only to making exhibitions and programmes for our present time, but to writing histories that will live on, that will continue to tell stories about who we are and about what is happening in this moment.’

The reopening of the Studio Museum, in other words, could not be more timely.

The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, reopens on 15 November.

From the November 2025 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.