The passing of time tends to mellow architecture, so that buildings that might once have seemed startlingly new or original appear politely respectful to us today. We are no longer shocked, for instance, to see a Palladian building next to a gothic one or an exuberant Victorian extension to an elegantly proportioned Georgian house.

The work of the Victorian architect George Devey (1820–86) is interesting in relation to this process because extreme shifts in style often occur within individual buildings that he designed. His large, rambling country houses have the appearance of historical collages, mash-ups that seem to belie any precise chronology.

Devey was a highly successful architect, mainly of country houses, but his reputation waned after his death and some of his projects remained obscure for many years. Jill Allibone’s biography, published in 1991, is still the only proper study of his work. Devey’s relative anonymity can be only partly explained by the passing of time and the cycles of architectural fashion. The nature of his work and the degree to which it sometimes blurred questions of historical provenance actively contributed too. In some ways, he was almost too successful in his integration of historic fragments and new elements, successfully writing his own work into at least partial obscurity.

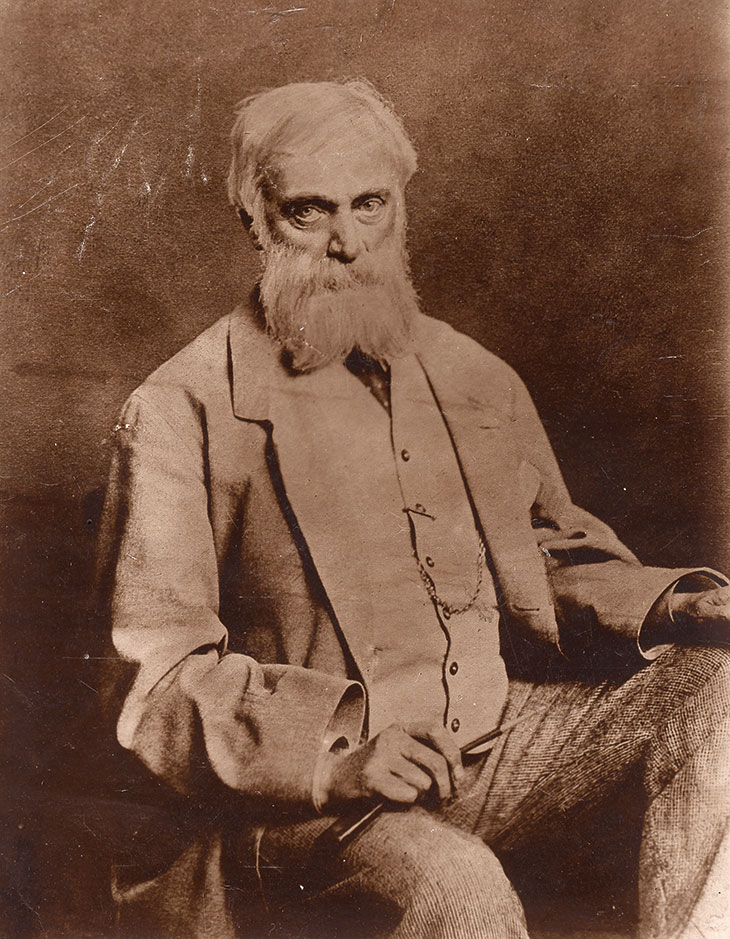

George Devey, photographed in 1880. RIBA Collections

Devey’s career took a long time to get going. Born in 1820, he initially trained as a watercolourist specialising in rural architectural scenes. In 1837 he became a pupil of Thomas Little, a middling architect of church buildings. Devey stayed with Little for nine years – an unusually long time for such a modest position – before setting up on his own. He then spent much of his early practice engaged in minor restoration and improvement projects. When he began to work on larger-scale buildings he took this sensibility with him, designing country houses and estate cottages that appeared as accretions of building work over time.

Betteshanger in east Kent, begun in 1856, was Devey’s first major commission, but even this was based around an existing structure. He started with a Gothic Revival house of 1829 by Robert Lugar and significantly enlarged it, making it look far older in the process. He added bays, stone mullions and casement windows in a manner that suggested a Tudor rather than early Victorian building. And he surrounded it with anachronistic additions: crow-stepped and Flemish gables, diapered brickwork, battlements and a timber cupola – a ragbag of historical styles and local references.

Materials shift from stone to brick in a seemingly random way, as if the whole thing has been patched together from parts over time. Devey even added ‘real’ bits of old structures, in the form of a small dairy building moved all the way from County Durham. The result is a strange chronological jumble, described as a ‘freakish Jacobean imitation’ by the historian Pennethorne Hughes in his Shell Guide to Kent.

Within the grounds of Betteshanger Devey designed a number of other buildings, a picturesque collection of estate cottages combining timber-framed jetties with monumental brick chimneys and diapered brickwork. He also redeveloped the nearby vicarage, an even more extreme affair that looks like the petrified remains of several houses joined together like Frankenstein’s monster. Devey’s work here is grotesque in the best sense of that word: distorted, mysterious, fantastic.

St Alban’s Court is just a few miles from Betteshanger. It was designed by Devey some 20 years later and represents his mature style at its most sophisticated. Here Devey genuinely started from scratch, designing an entirely new house that nonetheless suggests it has been built out of the ruins of a previous one. It is constructed mostly of red brick that sits on lower courses of stone. This rises and falls like a rubble wall, suggestive of ruins and carefully intercut with the precise and beautifully laid red brickwork.

St Alban’s Court, Kent, designed by George Devey and constructed in 1875–78. Courtesy Clive Webb/www.nonington.org.uk

The whole is noticeably cleaner, sharper and more controlled than his previous work, and the contrast between brick and stone is almost graphic in its clarity. By this point, Devey’s technique had become stylised to the point where it seems hard to imagine he genuinely intended the house to be read as anything but new. But, as Jill Allibone notes, Devey’s artifice continued to fool people into thinking that St Alban’s Court was built from the remains of a previous house.

Following his death in 1886 Devey’s office went into rapid decline. His work rested on the strong personal relationships he had built up with his clients, many of whom tended to employ him on multiple projects. He designed Betteshanger and its associated houses for Sir Walter James, and at St Alban’s Court he added cottages and almshouses to the nearby village of Nonington, all for William Hammond, a wealthy city banker. He worked extensively for the Rothschild family as well as for the Duke of Sutherland, and his early work at Penshurst was commissioned by Lord de L’Isle.

Devey had a reputation for employing less-than-brilliant assistants and this no doubt also contributed to the office’s demise. But one employee, Charles Voysey, did go on to great things. Voysey took Devey’s rambling picturesqueness and moulded it into something more taut and more precise. Devey’s studied referencing of historical forms of decoration and his monumental brick chimneys would also prove influential on the work of Richard Norman Shaw.

Devey’s primary stylistic innovation was the development of a fictive architectural history. He was a magpie with a painter’s sensibility, creating compelling images made up of fragments. No doubt this was attractive to his clients, at least partly because it established historical legitimacy for what were actually new-build houses. The architectural lineage conferred status and made the houses seem less like a new imposition and more something that had grown naturally over time.

The historian Timothy Brittain-Catlin argues that Devey was not so much producing a fictive history as attempting a genuine form of constructed archaeology. His work recreated building techniques and styles as a quasi-scientific experiment. In this sense, Devey’s buildings can be seen as the logical extension of the pictorial studies of Wealden houses that he did at the start of his career. And as Brittain-Catlin points out, such an enterprise would be entirely consistent with the Victorian penchant for scientific surveys and taxonomy in other disciplines.

Whatever his motives, Devey’s work holds much to interest us today. Read through contemporary eyes, his borrowing and blurring of styles suggests a playful and productive relationship to architectural history, one that challenges current ideas about authenticity. The contemporary orthodoxy is to make clear distinctions between old and new. When architects extend existing buildings they habitually articulate the join, emphasising the difference between one and the other. This distinction would have made no sense to Devey, who saw the history of a building as a continuous and evolving process. His early experience with humble repair work and extensions carried over into grander and more ambitious work that plundered the past and present with equal enthusiasm.

From the July/August 2018 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.