For its first online edition, Abu Dhabi Art (19–26 November) has invited six internationally renowned curators each to present an exhibition focusing on contemporary art scenes across the world. The Paris-based writer and curator Simon Njami, co-founder of Revue Noire journal and the driving force behind numerous groundbreaking exhibitions across Africa and worldwide over the past three decades, has curated the fair’s first display dedicated to contemporary African art. He talks to Apollo about the ideas behind the show, as well as how the African art world has changed since he began his career.

Why is this display titled ‘The Day After’?

It’s called ‘The Day After’ because I have a feeling that the time – to quote William Shakespeare – is out of joint. [In the wake of Covid-19], we are all trying to envision what the day after might look like – and I think that neither politicians nor economists are going to find a clever answer to that. You have to be in the field of fiction and imagination; if you look at the way Covid has been managed, people are pretending to know things that they can’t possibly know, and provide answers and truths where they don’t exist. An artist never seeks truth – they are making propositions that come from the imagination. It is up to artists to invent the day after.

How are African artists in particular going about this?

In Africa – and this is of course a subjective analysis – the measurement of time is circular, rather than linear as it is in Europe. For instance, in Africa – at least in the Bassa language of Cameroon – there are words for neither ‘tomorrow’ nor ‘yesterday’ in the language. [You refer] to the ‘day after today’, or the ‘day before today’ – everything is relative to the present. It is from the here and now that we think of the past and that we can envision the future, tomorrow being just another now.

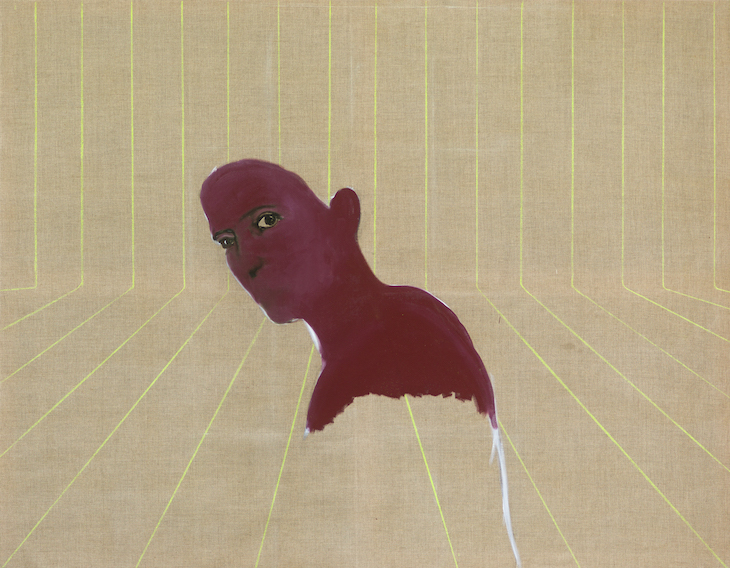

SORCIÈRES #9 (2019), Dalila Dalléas Bouzar. Galerie Cécile Fakhoury at Abu Dhabi Art

African art is more visible in the global market today than ever before. Do you think that this will change the way that art is made on the continent?

No – I think that Africa will change the way that the art market functions. When I started out as a kid in the early ’90s, there were no African artists in any of the major global shows. Working from a blank slate, you are forced to invent different ways of doing things – because these things cannot just be solved by market forces or by the critics. You have to come up with new rules of your own. You don’t do this because you want to but because there are no other options – it’s a do or die situation. We started small – I created a magazine with friends [the Revue Noire] – and then Okwui [Enwezor] came along, of course. And when you look at the map today you have a lot more African voices calling for change.

This is what is happening in the market – new galleries that don’t have the means or the experience of the old galleries are inventing their own ways of dealing with things. In the last few years there has also been the emergence of new fairs like 1-54 and Also Known As Africa – these show that an ecosystem is being built and that we are moving forward.

How did the Revue Noire help to set these wheels in motion?

First of all we were able to bring artists whom nobody knew to the attention of the world. But we also brought them to the attention of one another – all of a sudden artists discovered that there were other artists working and struggling with the same problems as they were. That was important – to have this feeling of being part of a larger struggle, if I may use that term.

I remember once I was in Kenya and I wanted to award a scholarship to a young artist there. He told me he wanted to go to New York and I said ‘No, I’ll send you to the Dakar Biennale’. He came back fascinated, and told me that in Nairobi he hadn’t known that there was so much happening across the continent, that there were such committed artists. This is the kind of thing that has helped to shape a new confidence.

Oka gusamie tweke okimana (2019), Kaloki Nyamai. Septième Gallery at Abu Dhabi Art

How might the recent focus on restitution of African material heritage change the way that contemporary African artists relate to the past in their work?

It’s not going to change anything – it’s the wrong debate. We are told that this is our heritage – but all the masks, sculptures, all those works that are exhibited in Western museums have nothing to do with what was left in Africa. It’s as if you’re dealing with a distant relative you don’t even know any more – they have been transformed by the Western market into something that is entirely different. I’m not sure that if some of them weren’t now worth millions people would be all that interested.

What about those artists who incorporate references to these objects in their work?

I would say that it’s a trap and that they should focus on their job. Africa’s been dealing with other things for centuries – why all of a sudden does it need these objects? I want people to stop telling me that they are part of our memory, because we have been living without those memories and so they cannot tell me now that we cannot survive without them. We survived because we had to invent, instead of being trapped in some wheel of thought about what was taken from us.

Who are the artists, in your view, who best capture this spirit of invention?

I never give names, but there are many – you just have to look at the shows I’m doing. What I’d say is that there is a group of artists now who are working to construct the future by supporting young people, providing them with resources to fight the fight. It’s about building the ecosystem – and that’s why I don’t want to name individuals.

How important is the growing market in the Gulf for contemporary African art?

Well, we can’t survive without it – but the UAE can learn from the mechanics of what is happening in Africa now as well. The future is certainly in Africa – we have the youngest population in the world. If the UAE starts to look away from the West to what is happening in Africa, then it will be one step ahead of the game.

Abu Dhabi Art is online from 19–26 November.