From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Indiana Jones, Assassin’s Creed, Lara Croft: popular culture has blurred the lines that archaeology likes to draw between treasure-hunting and methodical excavations. Yet scratch the surface of many archaeologists, writes Maria Golia in her new book, and an Indiana Jones is what you’ll find – a scholar fuelled by the thrill of stepping into spaces where time seems to have stood still.

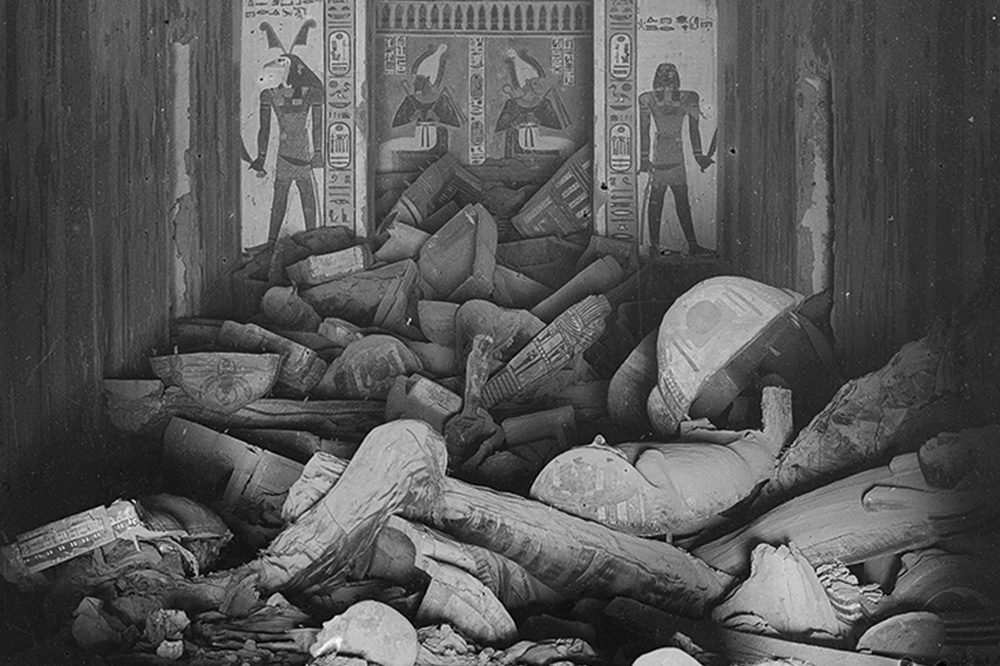

A Short History of Tomb-Raiding tackles a broad sweep of Egypt’s history through the lens of tomb-raiding and treasure-hunting. Golia uses these terms interchangeably to refer to any opportunistic searches for the material remains of antiquity. This lets her consider various forms of incursion, from outright thefts to spiritual quests and archaeological digs.

Funeral practices in ancient Egypt saw the upper echelons of society buried with personal possessions, offerings and ritual equipment needed for their continued existence in the afterlife. This meant that precious metals, perfume oil and rare stones were taken out of circulation and sealed away in tombs. Thieves flouted moral codes and ran the risk of capital punishment to retrieve this wealth. But there was also a certain honour among thieves, or at least some good intentions: around 1100 BC, at a time of unrest, robberies from tombs in Luxor’s Valley of the Kings let precious metals re-enter the struggling economy. Local priests restored the pharaohs’ ransacked bodies and removed them to a secret cliff-top location – perhaps helping themselves and their depleted temples to further riches as they did so.

Funeral practices in ancient Egypt saw the upper echelons of society buried with personal possessions, offerings and ritual equipment needed for their continued existence in the afterlife. This meant that precious metals, perfume oil and rare stones were taken out of circulation and sealed away in tombs. Thieves flouted moral codes and ran the risk of capital punishment to retrieve this wealth. But there was also a certain honour among thieves, or at least some good intentions: around 1100 BC, at a time of unrest, robberies from tombs in Luxor’s Valley of the Kings let precious metals re-enter the struggling economy. Local priests restored the pharaohs’ ransacked bodies and removed them to a secret cliff-top location – perhaps helping themselves and their depleted temples to further riches as they did so.

Golia devotes a chapter to medieval Arab interest in antiquities, overlooked in histories of Egyptology that centre Western sources. The ninth-century ruler Ibn Tulun was said to have stumbled, literally, over buried treasure while on horseback. With the riches, he built a hospital, helped the poor and established guilds of ‘seekers’ (mutalibun) who paid a 20 per cent tax on what they found. Arab scholars deplored the damage treasure-hunting did to sites such as the Giza pyramids and their adjacent cemeteries, where jinns were rumoured to punish thieves, or at least scare them witless. Historian Ibn Khaldun, in the 14th century, considered treasure-hunting a sign of society’s moral decay and treasure-seekers ‘stupid and deluded’ because they used magic to guide their search. Yet there was a touch of alchemical aspiration in the treasure-hunting manuals written at this time, which framed the practice as a quest for self-improvement.

One of those manuals, The Book of Hidden Pearls, was translated into French in 1907 by Ahmed Kamal, the first Egyptian curator at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. His boss, Gaston Maspero, reasoned that making the book available to more readers would deter unlicenced excavators. By the early 20th century, however, tomb-raiding had turned professional. From the 1860s, increasing tourism and foreign investment in Egypt stoked an already heated antiquities market. The writer Amelia Edwards described the ‘pleasures of the chase’ for artefacts on her first trip to Egypt in 1873: ‘The game, it was true, was prohibited; but we enjoyed it none the less because it was illegal. Perhaps we enjoyed it the more.’ Her travel companions bought a mummy but threw it overboard when it began to smell, as its resin coating melted in the heat.

That long-lost body may have come from the royal burials salvaged by ancient priests. Earlier in his career, Ahmed Kamal was part of a team that cleared one such cache, in 1881; the bodies included famous kings such as Ramses II. That cache, in the Deir el-Bahri cliffs, had been located a decade earlier by the Abdel Rasul family, who gradually sold off pieces to tourists. Their fence was Mustafa Agha Ayat, long-serving consul in Luxor for Britain and America and thus immune from prosecution.

Golia explains that the clearance of the cache, and the arrest and torture of the Abdel Rasuls, took place during the anti-colonial Orabi uprising that triggered Britain’s invasion of Egypt in 1882. It is one of the few mentions of empire or colonialism in the book, yet that context is crucial to understanding archaeology and the antiquities trade. A new generation of archaeologists, including Howard Carter, embraced both ‘scientific’ excavation and the money-making opportunities of the market, benefitting from the power that empire gave them. A colleague described Carter in approving terms as ‘just one white man administering justice to all that crowd of natives’ when an Egyptian farmer allowed his fields to encroach on land designated as an archaeological site.

In the final chapter Golia relates her own encounters with treasure hunters in 21st-century Egypt. Authorities have built seven-metre-high walls to separate archaeological sites from residential areas, as well as destroying animal pens, homes, and villages deemed to threaten monuments or foreign tourism. In Western media, colonial stereotypes of Egyptians as untrustworthy and unable to care for their heritage are rife, while the effects of inequality and a military state are real. No wonder treasure-hunting manuals still circulate, and illicit digging leads to many deaths, injuries, and arrests each year. Golia speaks to several small-scale seekers, but one assumes that serious antiquities-smuggling involves people much higher up the ranks.

Historical circumstances help explain why people keep digging up the distant past, but like many books on Egyptian themes, this one lapses into Orientalising tropes of timelessness (apparently pre-19th century Egypt was ‘quietly indifferent to the passage of time’). Although the book is engagingly written, its illustrations include several photographs of human remains, while the conclusion praises dubious efforts to animate the crushed voice box of an embalmed body in a Leeds museum. The exploitation of ancient burials for material gain has a long history, not a short one – and it seems we are still living it.

A Short History of Tomb-Raiding: The Epic Hunt for Egypt’s Treasures by Maria Golia is published by Reaktion Books.

From the October 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.