Are some images too harrowing to show? ‘Human Rights Human Wrongs’ at the Photographers’ Gallery begins with a spread of photographs revealing the unspeakable horror of the Holocaust: heaps of corpses, emaciated bodies and ghostly stares. These images, which were published in LIFE magazine in 1945, would be instrumental in the United Nations’ post-war reconfiguration of the world order, and the ratification of Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. It is thus shocking to see, one room along, evidence of concentration camps built by the British to quell the Mau Mau uprising the following decade.

Czechoslovakia Invasion (Prague, Czechoslovakia, now Czech Republic, August 21, 1968), Hilmar Pabel. The Black Star Collection, Ryerson Image Centre

Central to the exhibition’s narrative is this paradox: photojournalism’s role in opinion-making, but also its inability to prevent the continuous brutality of conflicts. More than this, it reveals the tension between human rights and sovereign rights, as countries across the globe became signatories to a legal framework to which they have not always adhered.

Curator Mark Sealy’s selection of 300 images from the Black Star archive acts as an inventory of oppression, torture and repression, but also courage, rebellion and liberation in the context of decolonisation and the Cold War. The show is a journey into 20th-century social and political history. Along the way, Sealy questions how information and images are managed by the media.

Biafra (Republic of Biafra, now the Federal Republic of Nigeria, c. 1968), Carlo Bavagnoli. The Black Star Collection, Ryerson Image Centre

While Article Six of the Declaration of Human Rights states that ‘everybody has the right to recognition everywhere’, the images display a conspicuously Eurocentric worldview. If it sets out to demonstrate a certain agency of representation, Lennart Nilsson’s ‘The Jungle Photographer’ series, showing an African portrait photographer at work in the 1960s, at once objectifies and exoticises its subject with its ethnographic undertones and cringeworthy title. Elsewhere, the African subcontinent is represented by the well-worn stereotypes of the savage, the child soldier, the recurring motif of starving people begging for food. As Sealy is keen to point out, these images rarely reveal the ideological and political conditions that made these things happen.

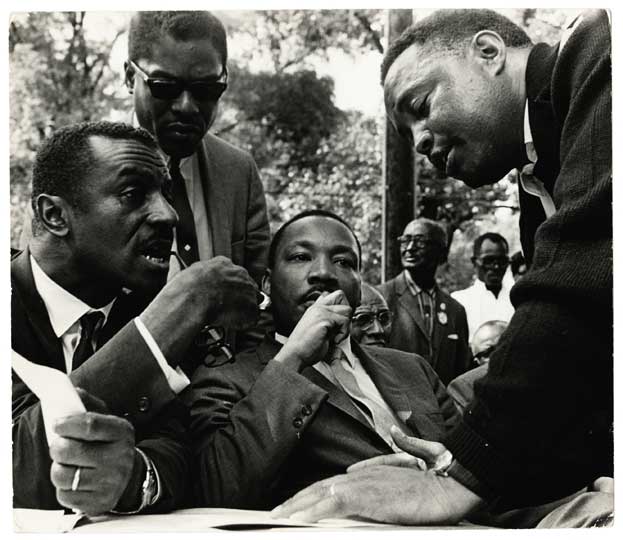

Sealy questions what happens when the state turns against its own citizens and why some lives are worth more than others. Among the exhibits is an extraordinary photograph of a woman at a demonstration in Georgia being pulled away by three policemen. It claims as iconic a status as Charles Moore and Bob Fitch’s records of seminal episodes of the Civil Rights Movement, the arrest of Martin Luther King, or 106 year-old El Fondren, born in slavery, exercising his newly gained right to vote in 1962.

Birmingham (Birmingham, Alabama, United States of America, May 3, 1963), Charles Moore. The Black Star Collection, Ryerson Image Centre

The way that one frames and displays images is also explored, and some of the show’s juxtapositions are deliberately shocking. The funeral of Stephen Biko is paired with a group portrait of women from the Ku Klux Klan. ‘Urban guerrilla’ Patty Hearst is seen alongside a row of infants killed in a bombing in Vietnam. Terrorist Andreas Baader is shown alive in 1976, and lying in a pool of blood the following year.

One feels torn between feelings of voyeurism and a duty to look. ‘How many hundreds of such pictures must we see before we begin to care and act?’ asked Noam Chomsky during the Vietnam War. Susan Sontag famously questioned the ability of such images to ‘strengthen conscience and the ability to be compassionate’, because their proliferation and subsequent familiarity has a numbing, normalising effect. According to Sealy, who wants us ‘to listen to pictures rather than look at them’, we turn away too quickly from these photographs. ‘Human Rights Human Wrongs’ makes the audience work, and jogs its historical memory. It makes us think about the power of images but, even more so, about their impotence.

‘Human Rights Human Wrongs’ is at The Photographers’ Gallery, London, until 6 April.

Related Articles

The scars of war: ‘Conflict, Time, Photography’ at Tate (Will Martin)

Oversaturated: the problem with Richard Mosse’s photography (Yvette Greslé)