The connection between the Royal Photographic Society and the Science Museum is an authentically historical one, dating back to the nascent Photography Society’s fifth annual exhibition in 1858 (the society gained its Royal Prefix in 1894). Back then, the South Kensington Museum, as it was known at the time, was crammed with hundreds of images, floor-to-ceiling, espousing the wonders of a new medium to a curious public.

The Two Ways of Life (1857), Oscar Rejlander. The Royal Photographic Society Collection © National Media Museum, Bradford / SSPL

Today, an acute awareness of that history remains. In what is only the third major exhibition to be held in the Science Museum’s wonderfully curated Media Space – which has been open little more than a year – it revels in the collection of the world’s oldest surviving photographic society. Spanning from the 1820s to the present day, over 200 photographs have been handpicked from the esteemed and comprehensive collection, some of which are bona fide cultural artefacts.

A trio of Joseph-Nicéphore Niépce’s ghostly heliographs from 1827 – made by covering pewter plates in bitumen and exposing them to the sun – are on show in a separate, celestially lit chamber. As the oldest images in the collection, they were created 12 years before even the announcement of photography. Other cornerstones of the medium are exhibited, such as William Henry Fox Talbot’s intricate and experimental ‘mousetrap’ cameras, as well as, a ‘travelling photographer’s camera’ from 1855, which is a hulking, gargantuan piece of equipment. These are images straight from the textbook, although in an exemplary, not fusty, sense.

The Turkish Bath (1986), Calum Colvin. The Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford © Calum Colvin

Eschewing chronology, classic photographs (such as Alfred Stieglitz’s 1902 Hand of Man) are hung cheek-by-jowl with modern – not yet canonised – classics including Calum Colvin’s The Turkish Bath from 1986. Martin Parr’s awkward, highly saturated snapshots sit beside Edward Steichen’s cool, monochrome portraits. In another section, meanwhile, images from different points in photographers’ careers are juxtaposed: Ernest R Ashton’s moody 1896 shot of the Pyramids contrasts with a stark Norwegian airship hangar in 1937. Elsewhere, there’s even a wall-enveloping ‘salon hang’ replicating the 1850s style.

This innovative approach to curation is refreshing, much in the same way that Tate Modern’s concurrent exhibition ‘Time, Conflict, Photography’ opts for themes over dates. Similarly, schools of thought and style are blended: secessionism, pictorialism, objectivity, and photojournalism to name a few. Though, given that the Royal Photographic Society’s raison d’être is to ‘promote the art and science of photography’, it’s no surprise that scientific processes provide the most eye-catching diversity in exhibition: gelatine silver to daguerreotypes, Cibachrome to C-types, photogravure to colour-transparency 35mm film.

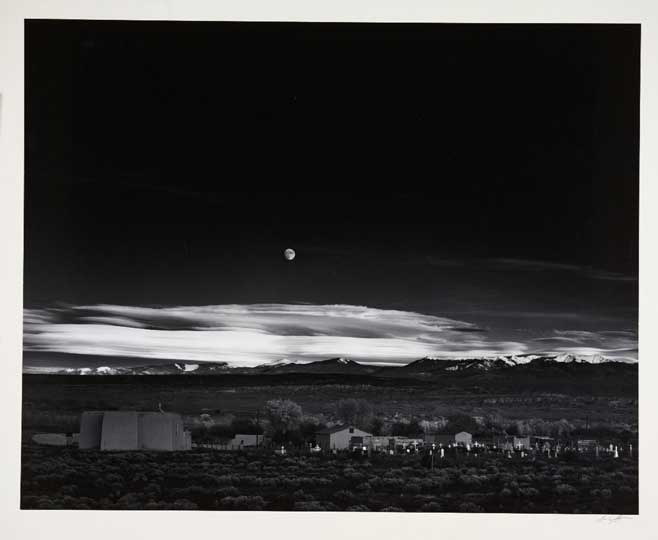

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico (1941), Ansel Adams. The Royal Photographic Society Collection, National Media Museum, Bradford © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

The Royal Photographic Society’s collection is by photographers, from photographers, and for photographers. That much is evident from the number of masterly pictures on show, even if there were a quarter of a million to choose from. Francis James Mortimer’s Spirit of the Storm (1911) conjures up the shimmering, late work of J.M.W. Turner; Margaret Bourke-White’s capture of Coney Island captivates; and Ansel Adams’ Moonrise in New Mexico (1941) beatifically bewilders. Perhaps the only problem with ‘Drawn by Light’ is that each of these images warrants more context to explain them, and more space to breathe.

‘Drawn by Light: The Royal Photographic Society Collection’ is at Media Space, the Science Museum, London, until 1 March 2015, after which it will tour to the National Media Museum, Bradford, from 20 March–21 June 2015.

Related Articles

The scars of war: ‘Conflict, Time, Photography’ at Tate (Will Martin)