From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

I’m picturing myself, aged eight, confronting the colour page of Peanuts in the huge Sunday edition of the Los Angeles Times we’ve bought on our way home from church – my father let me carry it into the house. I did not understand Peanuts at the time. In fact it seemed like a stumbling block, something in the way of the rest of the funny paper.

It could seem funny, if something funny happened; if one of them got hit with a snowball or laughably mis-spelled something (they all had to go to school and they weren’t very good at it and I could relate to that). When I first laid eyes on Peanuts, I thought gosh, these people are just heads. Is this supposed to be funny? Is it funny? Why is it in the funnies?

It had impact. My sister was baffled by the name and constantly called it Penis. My cousin was terrified of Lucy and couldn’t bring himself to read it.

It seemed so complicated. Linus, Lucy and Charlie Brown all had to talk so much. They couldn’t leave anything alone. In our family there were absolutes. What was done was done. The Browns and the Van Pelts lived in an anxious, fluid world. And that was precisely the point: they lived in the real world, and I didn’t.

Charles M. Schulz was born a hundred years ago in Minnesota. His father was a barber. Charles was a shy child who liked to draw – the early life of almost every cartoonist. He ended up drawing Peanuts for 50 years – almost 18,000 daily strips.

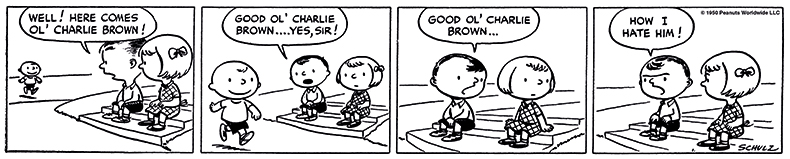

Charles M. Schulz’s lovable loser, Charlie Brown. Courtesy Charles M. Schulz Museum; © Peanuts Worldwide LLC

He loved winter sports (handy if you live in St Paul), especially ice skating. You will recall the hundreds of Peanuts strips that begin with Linus and Charlie Brown heading out of their houses with their skates slung over their shoulders. The most celebrated beagle in the world became a real star on the ice, and he never even used skates. They played at other things, too – football in the autumn, baseball in spring and summer. Does anyone even remember how to play horseshoes? And those baseball games. The other team always won. You never saw them, though you accepted that they existed in some Beckett-esque way. There was always some catastrophic failure of nerve, or a piece of totally inept fielding, for which Charlie Brown was to blame. Their nauseous, rocky baseball season had a lot of the sterling agony and discomfort of the New York Yankees.

But Charlie Brown strove to be a good manager, to encourage the unencourageable and the resentful. If it began to rain, he wanted to stay: ‘IT’S GOING TO CLEAR UP!’ he would be seen shouting, already all alone on the mound, obscured by the hundred beautiful lines of ink that Schulz used for rain.

Schulz was disappointed with some aspects of baseball – he thought Little League was too pressured and that the United States was obsessed with winning. At times he offered a kind of Zen alternative to thinking about sport. Lucy tells Charlie Brown to ask the ball if it wants to play; Sally, his little sister, once said to him, ‘You have to know how to talk to a beach ball.’

Peanuts was seasonal. This interested us as little Angelenos – we had no weather to speak of, but we could keep track of the year and what it portended through Peanuts. The characters led their own lives, as children do, or used to. Life in the United States is now rather different for children. They no longer roam their neighbourhood in search of a friend or a solitary adventure. They’re as scheduled-up and busy as heart surgeons. And as stressed.

Schulz lived most of his adult life in California, but the seasons of the Midwestern year remained in the strip. This particular neighbourhood had everything you might expect: houses, a school, parks, churches, small stores. It could have been almost anywhere in the United States at that time, possibly excepting California. The houses were modest, though the interiors seemed weirdly spacious. But when you’re a kid, your house does seem big to you.

The first Peanuts strip, published in seven newspapers across the United States on 2 October, 1960. Courtesy Charles M. Schulz Museum; © Peanuts Worldwide LLC

There were two comic strips in the 1950s and ’60s that really were about the United States: Peanuts and Walt Kelly’s Pogo. Between the two of them, they palpated, anatomised, operated, bandaged and pretty much saved us. Kelly’s cast of critters in the Okefenokee swamp held an ongoing and usually rather heated debate about the state of the country. Pogo was overtly political and satirical: Albert the alligator trying to keep up with JFK’s physical fitness campaign, after just inhaling an entire cigar. Kelly drew the Vice President of the United States, Spiro Agnew, as a jackal.

That would never happen in Peanuts, yet the very same things were considered there, on the flip side. Pogo revealed how we were being screwed, and by whom – Peanuts dealt with the lives and the feelings of the screwed. Peanuts was partly about the woes of the everyday life of adults in the nuclear age. You still had to go to your job (RATS!) and you went to church and you went to baseball games. But if you looked over your shoulder, there was Khruschev. And Sigmund Freud. (GOOD GRIEF!)

Much of the humour in Peanuts can be seen as psychoanalytic. Schulz was never on the couch by all accounts, but fear is fear, after all, and shrink talk was a kind of lingua franca of the 1950s and ’60s. It would be hard to believe that Schulz was not a fan of Jules Feiffer’s terribly insecure, more wildly drawn New Yorkers when they began to appear in the late 1950s. Peanuts-champion Chip Kidd says that the word neurotic first appeared in the strip in 1954, probably the first time it was used in an American newspaper comic.

There’s a lot of passive aggression. Two of the girls tell Charlie Brown that they’re going to have a party and ‘We’re not going to invite YOU!’ He responds, ‘If I have the kind of personality that annoys you, it would be silly to invite me.’ He is so happy to have come up with that.

There was an idea floating around that Peanuts was ‘Christian’. Schulz was a churchgoer, and he also taught Sunday school (to adults). But over the course of his life he said he had moved away from the Methodism he had grown up with, via a spot of Pentecostalism, toward a more ‘secular humanism’. When a religious commentary appeared, The Gospel According to Peanuts, Schulz said that the guy didn’t really get it.

Politics and the Bomb. Charlie and Sally Brown are watching a golf match on TV. The commentator says, ‘He’s down to the last putt and he can’t play it safe… There’s no tomorrow!’ Sally freaks out and runs outdoors, screaming ‘THEY JUST ANNOUNCED ON TV THAT THERE’S NO TOMORROW! RUN FOR THE HILLS!’

Charlie Brown has a box with a plunger – it’s attached to a long rope which is attached to Lucy. He says to Patty, ‘We’re playing “H-Bomb Test”.’ He pushes the plunger, the rope undulates and then Lucy yells, ‘BWHAM!’

Peppermint Patty and Snoopy out on the ice. Courtesy Charles M. Schulz Museum; © Peanuts Worldwide LLC

In 1952, an unusually direct reference to comics themselves: there was much public concern over violence in comic books (dear dead days). Charlie Brown’s at a rack of comic books labelled ‘For the Kiddies’ in a drug store. The comics on sale are: Mangle, Terror, War, Hate, Gouge, Kill, Slaughter, Choke, Murder, Ouch!, Stab!, Throttle, Crush, Hit!, Kick, Smash, Jab, Ruin, Slash and Blast.

As an artist, Schulz was a beneficiary of the New Deal – he trained in a cartooning unit of the Bureau of Engraving, where government pamphlets and propaganda were prepared. After serving in the army, he – again, like every cartoonist – simply began mailing in his work, hoping a syndicate would bite. When he was given the opportunity to do Peanuts (the cutesy name foisted on him by United Feature Syndicate), there was an immediate challenge: the space was minuscule – ‘The size of four air mail stamps,’ Schulz said. And this is why Peanuts looks the way it does: it had to be speech and figures. There was no room for backgrounds or fancy ink effects. Even when the strip became successful, and bigger, that is the way it remained. When people would ask him why there were no adults in the strip, he would say there was no room for them.

Let sleeping beagles lie: Snoopy on top of his doghouse. Courtesy Charles M. Schulz Museum; © Peanuts Worldwide LLC

Schulz admired Walt Kelly, and a very wild strip by Gus Arriola called Gordo, which drew graphically on George Herriman’s astounding Krazy Kat, the killer comic strip of the 1920s and ’30s. Herriman influenced them all. Silent comedy techniques, too, abound in Peanuts – the pratfalls are classic; Charlie Brown and the others use perfect Oliver Hardy ‘camera looks’ to put over moments of dreadful sober realisation.

‘Let’s try to just talk about it as pictures,’ Schulz said. ‘I am still searching for that wonderful pen line that comes down when you are drawing Linus standing there, and you start with the pen up near the back of his neck, and you bring it down and bring it out, and the pen point fans a little bit, and you come down here and draw the lines this way for the marks on his sweater. This is what it’s all about – to get feelings of depth and roundness, and the pen line is the best line you can make.’ A complete contradiction of much art school advice.

But he’s hugely minimising the importance of the words. Peanuts scripts are punchy. There’s never a superfluous word or one out of place. The vocabulary was rich, and subtle at the same time. Every American has said ‘RATS!’ in personal frustration and ‘GOOD GRIEF!’ in disbelief at the state of human existence. If you’re too gobsmacked to say ‘GOOD GRIEF!’ then you can say ‘AUUUGGGH!’ or scream ‘YAAAAA!’ as you run away.

As part of the Peanuts centenary celebrations this winter at the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California, there’s an exhibit focused on Schulz’s lettering (21 July–15 January 2023). He did everything himself, unlike many daily strip artists. When he began a new strip he started with the lettering – the script had the same energy, comedy and brains as the visuals. He never allowed the text to be squeezed by what else had to happen in the frame.

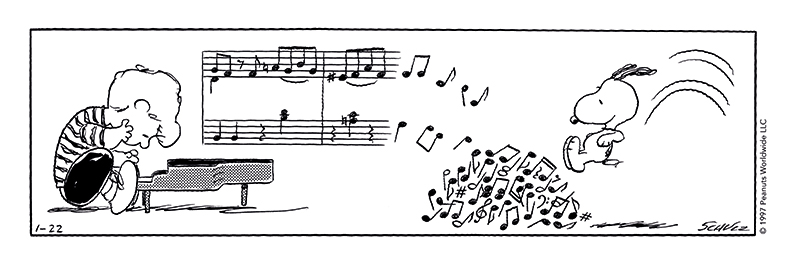

The Beethoven scores that Schroeder plays were hand-drawn by Schulz, who loved the composer almost as much as Schroeder does.

Schroeder and Snoopy showing signs of discord. Courtesy Charles M. Schulz Museum; © Peanuts Worldwide LLC

And the marketing of Peanuts was on this wise: as early as the mid 1950s, plastic figures of the characters were being produced. Then there were toys, board games, magic slates, talking Peanuts buses, even cocktail napkins (the grown-ups wanted in, too). The daily strips began to be collected as paperbacks, a number of which had vaguely threatening titles, such as Let’s Face It, Charlie Brown!, Watch Out, Charlie Brown, Who Do You Think You Are, Charlie Brown? These were everywhere – choking the streets and newsstands and people’s loos. The problem is that the stuff, the figures on their own, are much more innocuous in themselves than the strip is. Too sweet. Detached from the philosophy, the psychology, they’ve acquired a terrible cute meaning of their own, and that is why it’s all still so annoying. I don’t know if you have been to a university lately, but there are so many Snoopys – Snoopy keyrings, Snoopy phones, Snoopy backpacks and Snoopy fanny packs – dangling off the MBA students that if you’re in an elevator and someone makes a false move you could get seriously lacerated.

In the early 1960s I could feel something changing, the way the ground softens and rises up in spring. Happiness is a Warm Puppy appeared – Schulz’s first original book. A book should never be square, but that was it – the tsunami had struck and Snoopy became the premium tutelary god of the United States. And I thought, ‘I CAN’T STAND IT! AAAUUUGGGH!’

In December 1965, CBS Television premiered the first animated Peanuts TV special, A Charlie Brown Christmas. I was watching. There was an appealing quietude to it: long shots of the kids heading out into the snow, the snow driven by the brushwork of an appealing, understated jazz score by Vince Guaraldi. Visually the animation had the same sense of space, of American largeness, and perhaps peace, that the strip had. It was an unusual moment in television. Quickly though, the television specials came to contain a lot of filler, such as Snoopy vs the Red Baron, Snoopy dancing for minutes at a time, and gags pulled from the strips that were currently popular.

Schulz was firm with his creation: ‘All the loves in the strip are unrequited; all the baseball games are lost; all the test scores are D-minuses; the Great Pumpkin never comes; and the football is always pulled away.’ Bill Watterson, of the phenomenal Calvin and Hobbes, called Peanuts ‘a dark world’. And it is. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Schulz’s favourite writers were Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Flannery O’Connor. ‘It’s a kind of parody of cruelty that exists among children,’ Schulz said. ‘Because they are struggling to survive.’

It’s irrelevant, the discussion of whether or not Peanuts preached the gospel or social equality; if its message dimmed under the weight of its own marketing. It was enormous. Colossal. And we have spent our whole lives as the characters in it.

‘The Spark of Schulz: A Centennial Celebration’ is at the Charles M. Schulz Museum, Santa Rosa, from 25 September–12 March 2023.

From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.