Johannesburg

Continuing our series of interviews with individuals selected for the Apollo 40 Under 40 Africa

‘It’s a crazy thing to be doing,’ says Mikhael Subotzky. The artist’s recent shift into painting seems to baffle him as much now, as he speaks to me over Zoom from a hotel in Cape Town, as it did when I met him in his Johannesburg studio in September 2019, where he showed me some of the White on White canvases included in his first display of paintings, ‘Massive Nerve Corpus’, at Goodman Gallery’s Johannesburg branch earlier that year. These large-scale semi-abstract canvases, layered with strips of medical tape, are certainly a far cry from the documentary photographs with which the artist made his name in the 2000s; Subotzky himself wrote derisively in 2019 of ‘privileged white men […] with their oversized paintings and well-worked mythologies’. But it’s perhaps precisely for this reason that he followed the ‘crazy’ impulse to paint. Over the course of the past 15 years Subotzky has developed from an acute observer of societal injustice in South Africa into something more singular: an artist who investigates the forms and the mediums of racial and social privilege in which he says that he, as a white man, is ‘complicit’, shining a light on the nefarious colonial histories at their root.

White on White (or Blessings of Emigration to the Cape, after Cruikshank) (2019), Mikhael Subotzky. Courtesy Goodman Gallery; © Mikhael Subotzky

To begin with, Subotzky ‘never saw [himself] as an artist’; he had ambitions as a teenager to follow his mother into medicine, or to train as an architect. When he did opt to study art – he had spent a year backpacking before university, buying a camera to document his travels – his work was driven principally by the documentarian’s urge toward a kind of political truth-telling. For his breakout series, Die Vier Hoeke (The Four Courners; 2004), Subotzky photographed the inmates of Pollsmoor Prison, which sits incongruously within the middle-class Cape Town suburb of Constantia where Subotzky grew up. ‘In my mind at the time I was very much photographing these prisons for those kinds of social and political purposes – in the faith that if you’re showing the hidden parts of society it might have a positive effect, even a very small one.’ In 2005, works from the series were exhibited at Pollsmoor in the cell where Nelson Mandela was formerly incarcerated. Subotzky tells me he still thinks of it as ‘my best exhibition’. ‘The audience had the taste, the smell, the sounds of the prison, and a large number of prisoners managed to see the work as well.’

Johnny Fortune, Pollsmoor Maximum Security Prison (2004), Mikhael Subotzky. Courtesy Goodman Gallery; © Mikhael Subotzky

The photographs themselves remain a harrowing exposé of social divisions in Cape Town. Shot in a 360-degree panoramic format – an attempt, Subotzky says, to ‘capture the extent of the overcrowding’ – they are imbued with high drama; perhaps none more so than the astonishing image of one inmate, Johnny Fortune, climbing naked out of a laundry machine in which he has taken to washing himself. As well as Subotzky’s uncle, the documentary photographer Gideon Mendel, major influences on the artist include Joseph Kudelka and Robert Frank – but the attention to formal composition that defines his work ‘is also just about being a bloody perfectionist’. ‘Especially with documentary photography, beauty has a very complicated relationship with narrative,’ Subotzky tells me. ‘People like Sontag have written important texts on that. But I realised that I want my work to be visually powerful enough to draw people in, even if a kind of aestheticisation was a potential pitfall.’

Subotzky’s work in documentary photography culminated in Ponte City – a six-year collaboration he began with Patrick Waterhouse in 2008 focusing on Africa’s tallest residential skyscraper, in the heart of Johannesburg. Today the building gives the impression of a kind of Sauronic tower – it can be seen from virtually everywhere in the city, dwarfing every other structure – but it was built in the 1970s, Subotzky explains, as a modernist utopian project. ‘This mythology was actually more interesting than the building itself – it’s a form of hyperbole that really expressed what Johannesburg thought about itself.’

Low Rise Elevator Roof, Ponte City (2008), Mikhael Subotzky and Patrick Waterhouse. Courtesy the artists and Goodman Gallery

Subotzky and Waterhouse photographed virtually every square inch of the interior – every door, window and television; they requested portraits of every resident, and when refused they photographed the closed door. As they worked, Subotzky says, ‘what became apparent to us was that the modernist fantasy and the apartheid fantasy had come together to form this kind of bastard child, with this totally untenable idea that you can have people living harmoniously in a 54-storey tower block and that you can keep the races separate as well. They’re both equally outlandish, but they’d found a resonance together here, at that time.’ Ponte City was acquired last year in its entirety by SFMOMA. An exhibition, planned for last December, has been delayed by coronavirus.

A turning point in Subotzky’s career came with ‘Retinal Shift’, the exhibition arranged after Subotzky won the Standard Bank Young Artist Award in 2012, which opened at the National Arts Festival in Grahamstown before touring museums in South Africa, ending at Standard Bank Gallery in Johannesburg in 2013. The display marked the expansion of Subotzky’s practice from documentary photography in three discrete but related directions. It included his first work in film, made that same year. Moses & Griffiths is a portrait of two Black museum curators in their seventies who had spent their lives conducting tours at two colonial-era historic buildings in Grahamstown, the Settlers’ Monument and the Observatory Museum. When Subotzky met them, he was struck by the ‘radically out-of-date’ versions of ‘white man’s history’ they imparted ‘almost by rote’ upon their tours. ‘But these completely fell apart when they were just asked to tell their own stories’; the four-screen projection played back these personal stories, simultaneously with the ‘official’ tours, so that the viewer ‘was surrounded by a complete narrative’. ‘I felt like I’d chanced upon a structure for closing [a] wound. Both of them expressed to me that there was a kind of healing, in being given a forum to tell the stories they wanted [to tell] rather than those that were expected of them.’

Moses and Griffiths, Film Still 20 (2012), Mikhael Subotzky. Courtesy Goodman Gallery; © Mikhael Subotzky

‘Retinal Shift’ also saw Subotzky delving further back into histories of colonialism than he had previously – Who’s Who (2012) comprised eleven screens, each with a slideshow of portraits taken from a particular edition of the Who’s Who of Southern Africa, spanning 1911 to 2011. Finally, the show included the work I was looking back, an installation of 100 images from Subotzky’s career to that date. Many of these were shown with their protective glass smashed by the artist, expressing at once a sense of continuity and a kind of psychological rupture.

Subotzky’s desire to revisit his work comes in part from a ‘mistrust of images’, which he says ‘has been there from the very beginning’, but perhaps more particularly from his acute awareness of his own role in the construction of images. ‘The rotation of the lens gets in everybody except me, the photographer. In many ways, I am the unseen warden […] and so [my work has become] a question of how to allude to that, but also how to fight against it.’ (Foucault’s Discipline and Punish has, not surprisingly, been an important touchstone.) In the years since ‘Retinal Shift’ Subotzky has continued his enquiries into the ways that he inhabits his works in ambitious and inventive ways, from WYE – a multi-layered film, his first venture into fiction – to his ‘sticky tape transfers’, begun in 2014, with which Subotzky removed pigment from historic photographs with tape before reassembling them in collages.

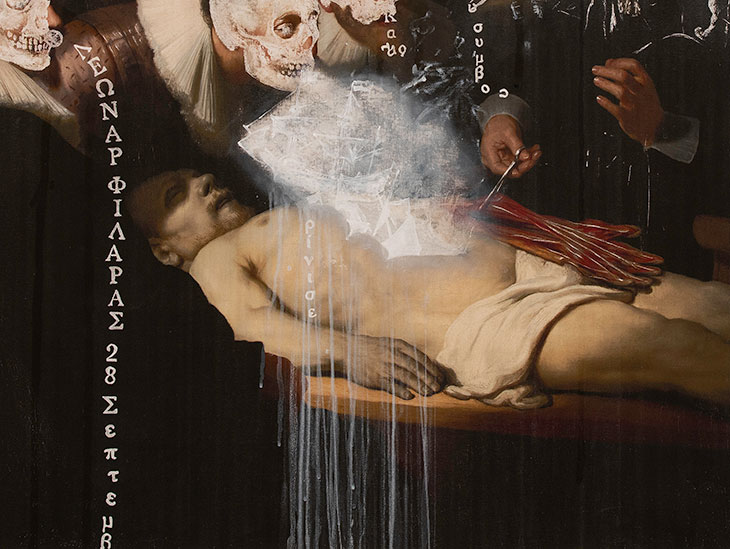

Detail from a work in progress by Mikhael Subotzky. Courtesy Goodman Gallery; © Mikhael Subotzky

Lockdown has presented Subotzky with what he calls ‘the perfect project’: an animated film which weaves the violent early history of the Dutch Cape together with explorations of John Milton’s blindness and ‘inner eye’ and of Subotzky’s relationship with his own father. Scheduled to be completed by next year, the film is a transhistorical look at the idea of ‘father figures’ – in art, in political nationhood, and in our own lives. ‘I’m using a photograph I took of my father walking into the sea,’ Subotzky tells me. ‘I must have taken it in 2010 or so – you know, I sometimes worry about getting stuck in a kind of death spiral of re-engaging with my own work.’ But it’s precisely this kind of relentless self-appraisal – the desire to look oneself in the face as honestly as possible – that has allowed Subotzky’s art to speak so forcefully to the generational repetitions of power and violence over the years. His art teaches us how to be vulnerable, and how to relinquish control.