An artist of paradox, L. S. Lowry has always divided opinion, and the current show at Tate Britain, ‘Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life’ has brought this to the fore. As the first major retrospective exhibition since Lowry’s death in 1976, over 90 works are displayed across six thematic rooms, offering a thought-provoking glimpse into the artist’s world.

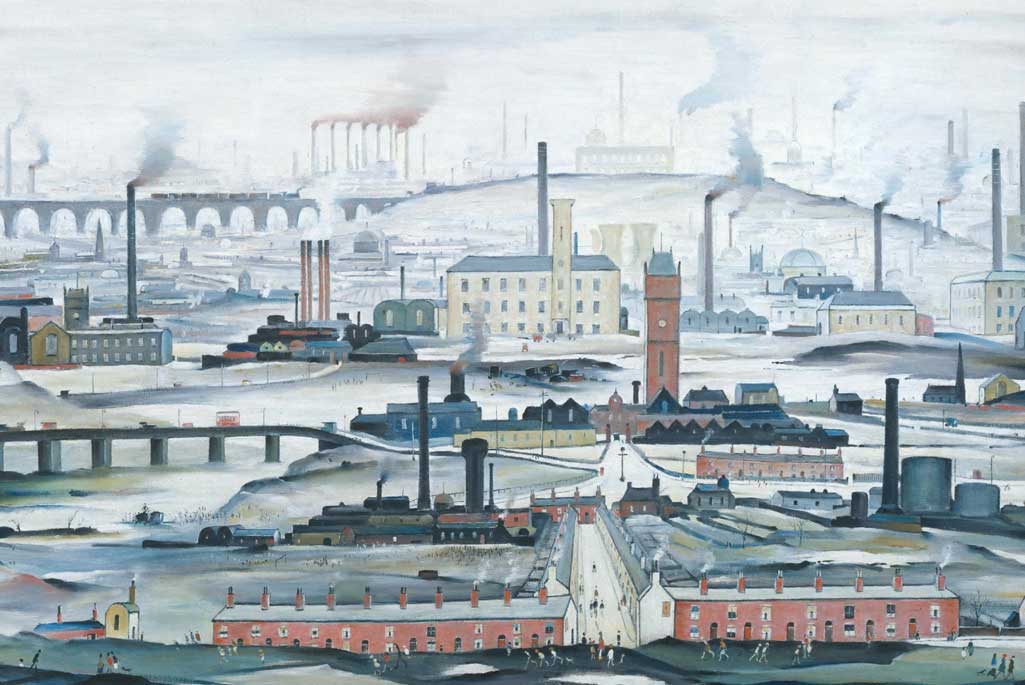

Lowry’s industrial scenes and urban landscapes offer a bleak and unwelcoming portrayal of northern England, representative of a world largely ignored by the south. The emotional detachment of Lowry’s pieces resonates with that of a modern viewer looking at his work. Yet, one cannot ignore the fact that his chaotic crowds and uniform terraced houses are powerful reminders of a time not so long ago.

T. J. Clark and Anne Wagner curated the exhibition with the intention of bringing Lowry back into the limelight. It is curious, then, that neither has specific connections with the artist’s work. Wagner is a celebrated historian of 19th and 20th-century French and British sculpture, and T. J. Clark is renowned for his focus on a new social history of art, concentrating especially on French Impressionism.

The curators attempt to situate Lowry within the wider parameters of French Impressionism. The exhibition’s title alone, taken from Clark’s seminal book The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Manet and his Followers (1985), sets up notions of how one should view Lowry’s work, pulling up his northern roots and positioning him in a different context.

In Room 2 – ‘The Idea of Modern Life’ – Lowry’s paintings are displayed alongside works by Van Gogh, Seurat and Pissaro, to illuminate how modernity affected society and artists’ visual representations of it. Van Gogh’s Outskirts of Paris (1886) portrays the depressing effects of Haussmannisation and urban sprawl, notions evident in Lowry’s urban scenes including Blitzed Site (1942) and Industrial Landscape (1955). But the connections seem contrived. Lowry clearly was not an impressionist, and the comparison – while undermining his stereotyped status as a northern naïf – serves only to highlight their technical differences.

Sectioned off into different themed rooms, ‘Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life’ is a confusing display, forcing fixed descriptions onto particular pieces, but it is strengthened by the inclusion of archival material such as photographs, newspaper clippings, personal letters and archive films, which situate the viewer more firmly in Lowry’s world.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Going to the Match (1953) portrays the action and energy found in the pleasures of working-class life, focusing on crowds moving toward the stadium. In a move away from urban centres, Hillside in Wales (1962) offers a more subdued landscape – although Lowry maintains a looming industrial presence through the inclusion of dark red clouds in the sky.

Ultimately, however, the exhibition makes Lowry seem like a one-trick-pony. An opportunity to paint a broader picture of the artist – by displaying works such as his seascapes and portraiture – has been missed. Such inclusions would have aided the curators’ attempt to dispel the stereotype of Lowry as a painter of matchstick men.

One cannot ignore the elephant in the room – why has it taken this long for London to produce a retrospective of one of Britain’s best loved artists? Tate has received criticism over its neglect of the artist, and ‘Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life’ inevitably carries a great deal of baggage, but one cannot deny its positive outreach, with people across the UK travelling especially to attend.

Whatever people think of his work, Lowry was undeniably a national figure, who through this blockbuster exhibition has been brought back to our national attention. As assistant curator Helen Little explains, this show is only part of Lowry’s story. Hopefully more will be told of it in the future.

‘Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life’ is at Tate Britain until 20 October 2013.