From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Stepping out of the airport on South Korea’s Jeju Island in August, seeing palm trees after the 55-minute flight from Seoul, I was overcome with joy. So many pleasures awaited! At the risk of sounding like a government tourism spokesperson, Jeju has something for everyone. Luxury resorts, beaches and golf courses dot this verdant island that is just south of the Korean peninsula and about half the size of Mallorca. For the active, hiking trails encircle the island and lead up Hallasan, the volcano at its centre, while gourmands can enjoy Jeju Black pork, grilled tableside and dunked into an anchovy-spiked sauce, as well as a panoply of locally grown citrus fruits.

I am not the only one aware of Jeju’s appeal. There has been a huge increase in the number of tourists in recent decades, from about 4.2 million people in 2001 to 15.3 million in 2019, more than 20 times the native population. Almost 90 per cent of visitors are South Korean, drawn by the easy trip to the balmy weather and open space in what has become known as the Hawaii of Korea. (As the pandemic has eased, it has become especially alluring: a vacation without Covid travel restrictions. On my previous trip in colder weather in early 2021, it felt deserted. This time, it was packed.)

The recent rapid development of Jeju has also involved the opening of an astonishing array of museums. There are tourist traps, palaces built by collectors and corporations, memorials to individual artists and ambitious public ventures. There is the World Seashell Museum, the Teddy Bear Museum and the Osulloc Tea Museum – a firm that grows its product on the island and opens a tea house at the Seoul branch of Pace Gallery this month. There are also more than 20 art museums, which, at their best, can provide a lucid sense of the island’s history and culture.

The Teddy Bear Museum at the Jungmun Resort on Jeju Island. Photo: Qiongna Liao/Alamy Stock Photo

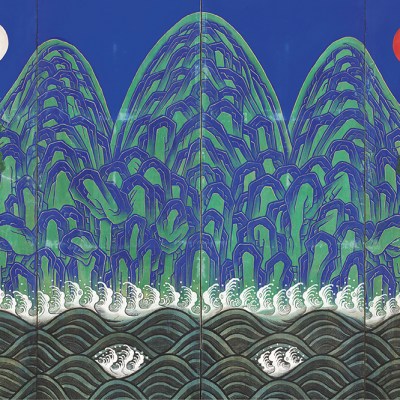

When I stopped by the Tadao Ando-designed Jeju Museum of Art, it was toasting its recent acquisition of a masterpiece by Chang Ree-suok (1916–2013), a Pyongyang-born painter who was a refugee in Jeju during the Korean War. Nearly 5m wide and 2m tall, The Workers of the Sea (1985) has about a dozen haenyeo – the island’s heroic free divers – busy along a seashore. One nurses a baby, another reclines topless, some bring in a catch that might feature abalone, octopus and other delicacies. A spectral pink-purple light suffuses this intimate yet action-packed scene. I wish I had gotten to see what it looked like hanging at the Seoul headquarters of its donor, the Export-Import Bank of Korea. (I was, at least, lucky enough to see haenyeo hard at work the next day.)

Sadly, the neighbouring Love Land park, a preserve of explicit erotic sculpture, has been closed for refurbishment since late last year and so I headed to a nearby bus stop. (Frankly, it is unwise to explore Jeju without a car. I was riding buses because I am a man of the people, and cheap – and because I was waiting on my international driving permit renewal.)

About two hours later, soaked from a brief rainstorm, I was at the Kim Tschang-yeul Museum of Art, named for another artist who spent time on the island during the Korean War. Kim, who died last year at the age of 91, devoted his art practice to rendering water drops on canvas and hemp, and a fine selection of them were on view in capacious rooms designed by Hong Jae-seung. The artist gave more than 200 pieces (including a few rare sculptures) to the institution, which opened in 2016 in a wooded spot on the south-west quadrant of the island. With its dark hallways and central water-filled courtyard, it is something of a sanctuary, perfectly matched to its site.

In contrast, one of Jeju’s newest art institutions, the Podo Museum, feels as if it could exist anywhere. A boxy and undistinguished structure, it was inaugurated in 2021 by the SK conglomerate, which touches everything from telecommunications to gas stations (it has a hotel down the road). It was hosting an earnest (if trite) year-long group exhibition called ‘Yet, With Love’ that aims to highlight marginalised groups living outside their homelands. A rainbow sign by Ugo Rondinone – Long Lost Happy (2020) – adorns the building and, inside, Yoko Ono’s Add Color (Refugee Boat) of 1960/2022, invites visitors to paint messages over a boat and the surrounding walls and floor.

Yeondoo Jung’s contribution includes the sculpture Picture Brides (2022), of women who left Korea for Hawaii in the early 1900s to marry Korean labourers they had never met. They are strange, vivid pieces, made of sugar, an allusion to the sugarcane fields where they worked. I wondered what they have thought of the scent wafting through one space, made with the brand Conte de Tulear to capture (in the words of a wall label) ‘the fresh, sweet, and sorrowful scent of the sugarcane, sweat, and rich soil the picture brides breathed in’.

The nearest bus stop to the Podo that I could locate was a 20-minute walk down

a long highway, and so a taxi ferried me in the direction of Jeju City to the grounds of a one-time tangerine orchard, where a converted citrus storehouse has become a handsome and compact nonprofit space run by Seoul’s Gallery 2. It was showing about 30 of the famous black-and-white photographs that Han Youngsoo (1933–99) took of the South Korean capital between 1956 and 1963, as the nation was just beginning its rapid economic ascent. In these images, long-vanished electric trams cruise the streets. Women tote laundry atop their heads. A young girl peruses a ramshackle book store.

A lot has changed since then in Seoul – and on Jeju. Also on the site of the former tangerine orchard, a shed has been converted into a cosy cafe. It is possible to imagine the island one day becoming overrun with visitors, and with cultural attractions, but that still feels a long way off. As I lingered over a tangerine latte, I glanced occasionally to see when the next bus was coming, but I was in no rush to leave.

From the September 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.