From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In mid August, when the UK’s attention was caught between riots at home and the Olympics in Paris, Historic England released a report with the punchy title ‘Multidimensional creativity as a mediator between cultural heritage and regional economic development in England’. A pre-publication release to the Observer ensured that the public were primed for what the report wanted to achieve. ‘Invest in heritage to boost wealth of failing English towns, says new report,’ was the headline.

It is not hard to understand why Historic England should want to make a case for better support of what it calls ‘heritage’ buildings. The organisation responsible for listing buildings, helping people ‘celebrate England’s spectacular historic environment’ (according to their website) and ‘champion[ing] historic places’ can clearly find a use for new forms of funding for ‘historic buildings’ – though its attitude to the unspectacular side of the historic environment remains unknown.

The report itself is, unsurprisingly, less clear cut than the headlines. Its author, Silvia Cerisola, concludes that ‘the potential of cultural heritage for being a resource for economic growth in England has clearly emerged.’ There is perhaps some conflict between that ‘potential’ at the start of the sentence and the more definitive ‘clearly emerged’ at the end, but either way there is still possibility for doubt.

These conclusions are based on what Cerisola calls an ‘econometric model’. If you are new to econometrics, the IMF parses it as follows: ‘econometrics uses economic theory, mathematics, and statistical inference to quantify economic phenomena […] it turns theoretical economic models into useful tools for economic policymaking.’ The problem with econometrics – which, in this report, translates different factors, including artistic creativity, scientific creativity and economic creativity, into values for an equation – is that the result will only be as good as the data you have. I am not convinced that it is easy to translate artistic creativity into a number. Cerisola acknowledges this: ‘there are in fact two main approaches to the measurement of this intangible and elusive concept,’ she says. The main measurement she uses is an ‘occupational approach’, whereby ‘artistic creativity is measured as the share of people performing creative tasks in artistic sectors’. As a primary school teacher might tell you, a good art lesson might well include the whole class but that doesn’t necessarily improve the paintings on the wall. So what are we really measuring?

At the heart of the report is the idea that investing in historic culture, which I think means old buildings, will give you more economic and creative activity. It essentially boils down to: if you give more people tree saws, forestry output will go up.

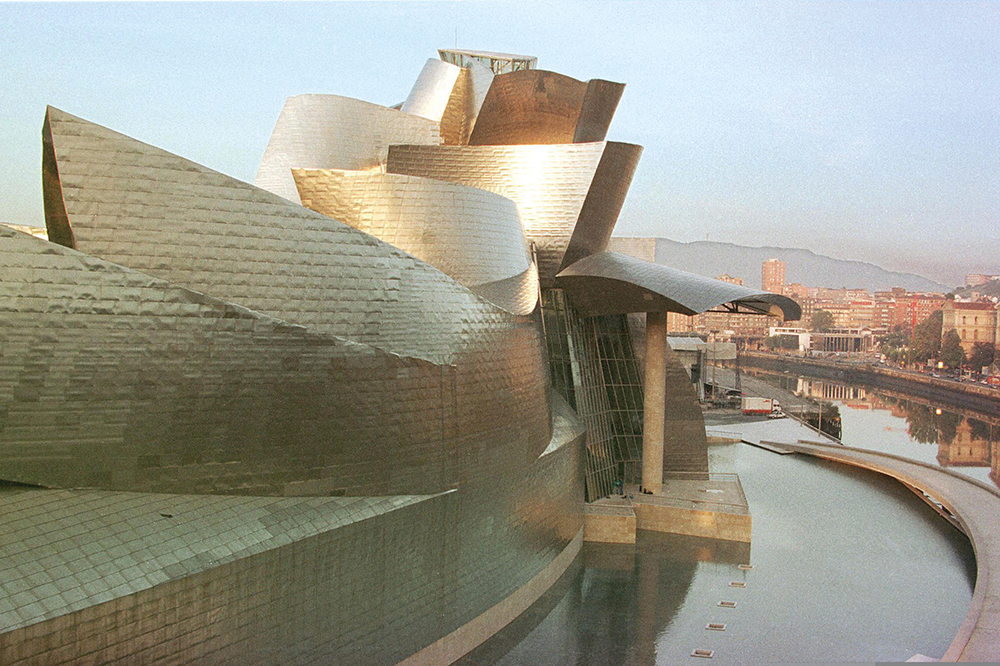

Politics might be the art of the possible but if you talk only about what is achievable, rather than what might be genuinely beneficial, then you are selling the arts short. This is a long way from J.M. Keynes’s claim that economists ‘are the trustees not of civilization, but of the possibility of civilization’. Ever since the transformation of Bilbao that began in the late 1990s, policymakers in the UK have used economic output as the justification for putting money into the arts. The problem is that artists are never as efficient as fund managers and if you really want to build a case for the arts you might need to do the work to justify them on their own terms. In 1997, a New Labour government was only too happy to accept the economic arguments for investing in the arts and in what it called, in a piece of circular logic, the creative industries. More than 25 years later, the arts have never been more impoverished.

From the September 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.