Early in my phone conversation with Rashid Johnson, the subject turns to music. ‘I’m a head,’ he tells me, by way of explaining the breadth of his musical knowledge, which includes early hip hop, avant-garde jazz, and even some country. Johnson’s voice audibly brightens when I bring up Sun Ra, the musician who fronted the Arkestra ensemble and played marathon concerts of his unique fusion of jazz and funk, while proselytising about Afrofuturism in between sets. Johnson understands why Ra insisted that he was from Saturn. ‘If you asked me to interpret that,’ Johnson offers, ‘I would say it’s that he felt so disenfranchised in America that he produced a distant space to which he could feel he belonged. I identify with that. I understand how frustration and disappointment can lead to feeling challenged to identify with the place that’s supposed to be home for you.’

Indeed, Johnson’s own work has long incorporated themes of escape. In 2008, as a conceptual project he created The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club, a fictional community that he represented through black-and-white photographs of its supposed members, a group of well-dressed, erudite-looking men. A recurring motif in his sculptures, paintings, and collages is the scrawled word ‘Run’, which evokes the artist’s hastily scribbled signature, but mostly suggests a desperate call for retreat. For a commissioned sculpture at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow in 2016, Johnson made a large-scale version of the coated-steel cube sculptures he had been developing over many years. The open-frame grid was filled with tropical plants and books by prominent Black writers, and ‘Run’ was emblazoned in spray paint on a yellow background as part of the work. In an interview with curator Kate Fowle in 2016, Johnson commented on his use of the word: ‘This has something to do with the evolution of the Negro escape strategy, which encompasses figures such as Marcus Garvey, Sun Ra, Kwame Nkrumah, and even the writer Paul Beatty.’

The New Negro Escapist Social and Athletic Club (Kiss) (2011), Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Rashid Johnson

It’s hard to imagine a time when the desire for escape has been more widely felt. The year 2020 has left most Americans feeling utterly shell-shocked. First there was the pandemic and ensuing lockdowns, and then further tragedy struck: a Minneapolis policeman knelt on the neck of George Floyd on 25 May, publicly suffocating him to death in broad daylight. Throughout spring and summer protests surged throughout the United States. In mid August, a few days before my interview with Rashid Johnson, a riot erupted in his hometown of Chicago. (Johnson now lives in New York with his wife, the artist Sheree Hovsepian, and their young son.) By late summer the chain of events leading to this riot was familiar: protestors take to the streets in Portland or Seattle or New York or Kenosha, Wisconsin, or half a dozen other cities, peacefully but firmly demanding justice for the Black lives taken by police officers. Then a current shifts, and the ‘rage of the disesteemed’, as James Baldwin put it, flashes through the crowd. Police cars are set on fire, shop windows are smashed, stores are looted. By morning Chicago’s so-called Magnificent Mile looked less like a luxury shopping strip than a war zone.

Johnson and I did not directly touch on the riot in Chicago, but it was part of the backdrop of our conversation: Johnson is now in the unenviable position of having interviewers ask him what it is like to be a Black artist during what feels like a national reckoning of longstanding racial injustice. The renewed force of the Black Lives Matter movement triggered a wave of acute reflection, if not quite an awakening, among individuals and institutions. Arts institutions in particular were taken to task for tokenising and ‘art-washing’, that is, actively exhibiting artists of colour, yet making little effort to diversify their curatorial staffs or boards. As a result of all the scrutiny, museums have been doing much hand-wringing, if little targeted action or restructuring. Discussing this highly sensitive topic, Johnson is careful to avoid generalising.

‘I am a particular kind of artist,’ he points out. ‘I work as a painter, sculptor, and picture maker, and film-maker. I’ve been lucky to have a certain amount of success as an artist, so that has to go into how I think thematically about what it’s like to be a Black artist. The question then becomes more like, what is it like to be a Black artist who has a certain amount of success who works in a certain set of mediums with the diverse concerns that come with that. From there, it’s like, I’m a man, right? So, what’s it like to be a Black male artist with a certain amount of successful works and a diverse number of mediums?’

Joy Inside My Tears (2014), Rashid Johnson. Photo: Martin Parsekian; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Rashid Johnson

Johnson’s mother is an academic specialising in African history, and it is clear that the pedagogical apple has not fallen far from the tree. In other words, Johnson is inherently patient and really good at explaining things. ‘So it has to get really granular,’ he continues, ‘but I would say from my position, a lot of people have expressed an investment in exploring themes and topics and things that have concerned a lot of Black artists in the past. We are in some ways put into a position where the expectation for facilitating the thirst and the knowledge and the information that people want to get from Black-themed cultural production has put a lot of pressure on people to find ways to explain how and in which ways their work should be read. And so it can be really quite dangerous in that respect. It can be really complicated. It can be exhausting. It can be deeply rewarding, because people are expressing real interest in how you work […] So when the work is viewed through the lens of, what is it like to be a Black man making art, being conscious of cultural themes right now? I guess the answer is, for me, not totally different than it was before, but I’m answering the question more.’

It is no wonder Johnson is adept at answering the question. He has been answering it publicly since his breakthrough in 2001 with the celebrated exhibition ‘Freestyle’, curated by Thelma Golden at the Studio Museum in Harlem. As the youngest participant in the exhibition, Johnson’s use of a large-format camera and a 19th-century printing process to create textured, intimate portraits of homeless Black men immediately put him on the map. Eleven years later, his work was the subject of a well-received exhibition originating at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, that travelled to Miami, Atlanta, and Saint Louis. Today the artist has a number of solo museum shows under his belt, and also directed an award-winning film adaptation of Richard Wright’s Native Son, which premiered on HBO last year.

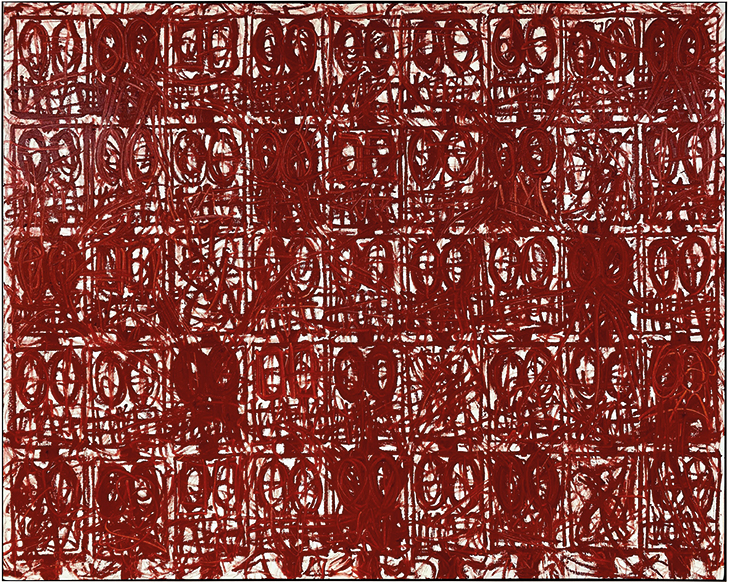

Anxious Red Painting August 20th 2020 (2020), Rashid Johnson. Photo: Martin Parsekian; courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Rashid Johnson

This autumn, Johnson has a major show opening at Hauser & Wirth’s London galleries (6 October–23 December). The show consists of his large-scale paintings and tiled mosaics, including an updated version of his Anxious Men series, rendered in a scratchy, agitated style that evokes both Dubuffet and Basquiat. Johnson says that he deliberately employs abstract techniques to allow the viewer to believe that they could be the person represented by his paintings. When asked why that was important to him, he explains that he likes the idea that ‘I’m not alone’. Johnson clarifies by reflecting on his fruitless searches for other Black faces in the paintings he looked at when he visited art museums during his youth. ‘I gravitated towards the work that allowed me to see my own relationship to it and a lot of times that was through abstraction. I can look at Pollock and think, “Oh yes, this takes on Western themes. This is a white male artist in a canonised white male context.” But I could see my own energy there. I could see themes that I think mattered to me in the work.’

As a jazz fanatic who used to frequent the Jazz Record Mart in the Loop during his student days, Johnson recalls that as he took in the syncopated rhythms of Pollock’s drip paintings, he recognised its improvisational technique. ‘It felt like abstraction shared a history with jazz and improvisation and it felt like we all owned it.’

In addition to abstraction, Johnson also gravitated toward postmodern conceptual art, particularly David Hammons, who incorporated materials that evoked African American culture, such as chicken bones and basketball hoops, into his incisive sculptures. Seeing Hammons’ work for the first time, Johnson recalls, ‘I felt like, “Oh, I’m here. I’m represented here.”’

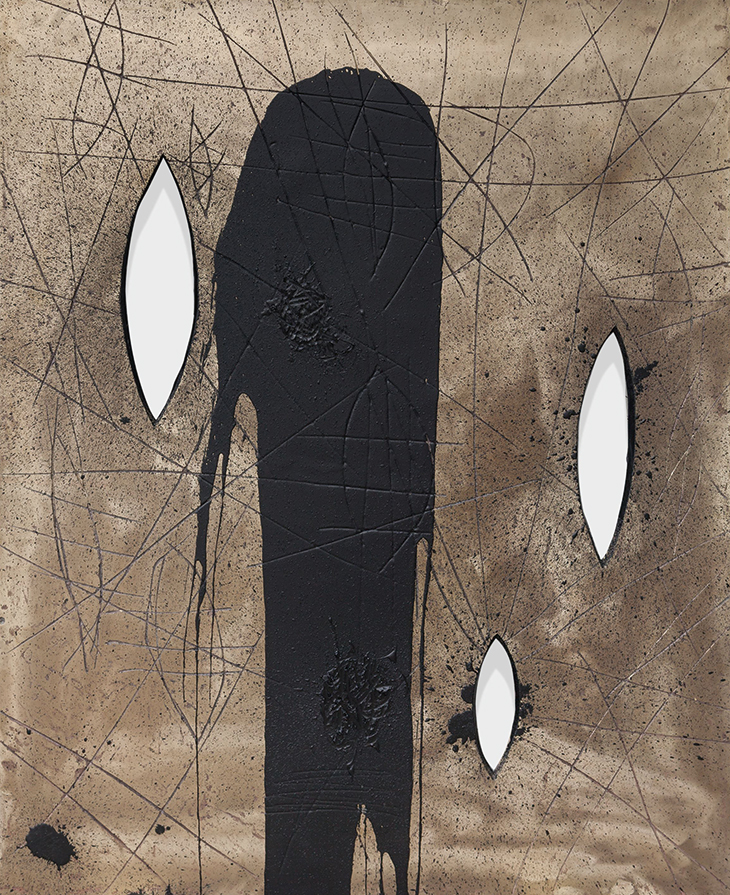

Falling Man (2016), Rashid Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth; © Rashid Johnson

Johnson is openly deferential to his predecessors yet hardly in their grip. He has forged his own striking visual language, largely through the use of specific materials, including shea butter and ceramic tiles. The shea butter explicitly functions as a signifier of African identity, marketed as such to the diaspora who crave an authentic tie to the continent. Johnson sometimes carves the dense, gold-coloured shea butter into semi-geometric chunks and pushes them together on tables of his own design, allowing the shea butter to crumble and fall apart. Or he presses it into concave steel tables, so that it resembles a bird bath full of lard. The tiles, however, are more personal, relating to a moment when he was still studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC), and anxious about his future. To relieve his anxiety, he tried going to a Russian and Turkish bathhouse, and found it transformative. For one thing, former presidential candidate and activist Jesse Jackson was there. But it also turned out to be an unusually tolerant environment. Johnson went into the ‘Russian room’ which was covered in white tiles. There was an unwritten rule that bathers would stare at the wall to give their neighbours privacy, and Johnson began thinking of the white wall as a canvas of sorts. He also used it as an off-campus study room, bringing in photocopies of the tough theoretical readings he had been assigned at SAIC, such as Derrida, or Deleuze and Guattari. The other bathers would ask him what he was reading, leading to informal seminars on such texts as Franz Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth. ‘It was really an interesting time in my life. I was growing in ways that I couldn’t have expected. I was exposed to themes and ideas that were fresh and new. I was in a basement with men, shvitzing, and it was a portal.’

Johnson incorporates the tiles into his mosaic paintings, along with wood, brass, and mirrors. The various materials become part of a vibrant, colourful composition in which geometric shapes compete with messy splashes of paint and seemingly random configurations. In his latest mosaic paintings, the ‘anxious man’ figure emerges, showing up in groups and pairs, each face wide-eyed and with a skewed, gaping mouth.

Asked to describe the people who frequented the bathhouse, Johnson remembers an unusually diverse group of men who would drop their inhibitions, and talk openly with others in an intimate environment. ‘The tile became one of the signifying materials of that place. It became kind of a spiritual signifier and theme, representing a place where I got a lot of relief.’

Johnson continues to go to the bathhouse in New York, or did, until it was temporarily shut down by the pandemic. These days, he is confined to his home and studio. The global ‘pause’ has given the artist some space and time to think about recent pressing social issues and how to address them. In the art world, in particular, Johnson has a sound, concrete suggestion. He would change the criteria that people use to evaluate candidates for jobs.

‘People think that internship programmes at certain prestigious institutions are the best ways to vet someone’s investment, and seeing the sacrifice of those jobs, which often come with little pay. But there are people who can’t afford to participate in that strategy. Who aren’t being subsidised. And I think that it’s problematic, the hiring practices and the vetting practices for both galleries and cultural institutions. We need to find ways to bring in qualified, thoughtful, and serious contributors from different backgrounds. I’m not the only person with that concern. We’re seeing a push to bring in diversity behind the scenes, outside of the cultural producers, the artists who are the lowest hanging fruit to invite in. How do we see Black dealers? How do we see more Black curators, more Black museum directors? I would like to see the criteria in ways that we evaluate that talent change post-haste.’

Installation view of ‘Within Our Gates’ at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, Moscow, Russia in 2016. Photo: Alexey Naroditsky; courtesy Garage Museum of Contemporary Art; © Rashid Johnson

Today, Johnson is leveraging his own position as a successful artist to expand his practice – not only making films, but also doing projects that are more pointedly oriented around social justice. In September, MoMA PS1 reopened to the public after being shuttered for several months, with a new commission by Johnson. Just as she commissioned Johnson to do a major project for the atrium at Garage, Kate Fowle, who was appointed director of MoMA PS1 last September, asked Johnson to create a project for the museum’s ample courtyard (until autumn 2021). A long concrete wall separates the museum from the surrounding neighbourhood in Queens, and Fowle wanted a project that would somehow overcome any perceived divide between the institution and the local community. Johnson came up with an elegant solution: a platform on which stand five microphones at different heights – one as tall as seven feet, and another about a foot and a half from the ground, perfect for a child. Another is chair-height. The raised platform evokes the famous speaker’s corners in Harlem and Hyde Park, while the classic SM58 microphones deliberately recall early hip-hop artists such as Eric B. & Rakim, who got their start in the Queensbridge Houses, a public housing development not far from PS1. In theory the microphones are available to anyone to use, and their words will be recorded and archived – and sometimes broadcast later via the museum’s website. When I spoke with Fowle about the project, called Stage, she reported that Johnson had just put the finishing touches on the surface of the platform, scratching faces on to its surface by hand with a sharp tool. But the project poses some problems in the age of Covid: ‘People want to speak out, but there is a risk to speaking out.’ Nevertheless, she adds, ‘Working with Rashid is incredible. The stage is his work, but it is completely open to us to work with.’

It’s a perfect capstone for 2020, one that embodies the artist’s shifting ideals. Instead of seeking portals or means of escape, Johnson is now keeping both feet steadily on the ground, determined to improve the world we have, the place that is supposed to be home.

Museums and galleries in the UK are closed from 5 November due to Covid-19. For more information on ‘Rashid Johnson: Waves’ at Hauser & Wirth, London, visit the gallery’s website.

From the October 2020 issue of Apollo. Preview the current issue and subscribe here.