I am standing in Mary Corse’s studio, a large white box with a sloping flat roof that she built two years ago beside her home in the wild landscape of Topanga Canyon, just a few minutes north of Santa Monica. She has lived on the same secluded property, first with her two sons and now alone, since 1970. One side of the studio is given over almost entirely to sliding glass doors which frame a stunning view of the Santa Monica mountains, green with chaparral and live oaks, with ochre rocks jutting in between. Corse apologises for the emptiness of the studio; it is late May, and several new works have just shipped to her solo exhibition at Lisson Gallery, London (11 May–23 June), while a long-term installation of her paintings opened at Dia:Beacon a few days earlier, following the institution’s acquisition of three works from the 1960s and ’70s and another from 2010. Many more pieces have been gathered at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where her retrospective – the artist’s first solo museum survey – opens in June (until 25 November).

Installation view, ‘Mary Corse’ at Lisson Gallery, London (11 May–23 June). Courtesy Lisson Gallery & Kayne Griffin Corcoran; © Mary Corse

One painting remains, however, resting on a trolley, half tucked behind a wall. It is a square composition of three crisp vertical bands inflected with off-white brushstrokes; Corse asks me to help her drag it out to where we can see it better. The canvas is from her White Light series, a recent example eight-and-a-half-feet square which she is repairing after a bird flew into it. Since 1970, Corse has sharply bevelled the edges of her canvases, so that their frontal planes appear to float magically a few inches away from the wall.

Corse becomes excited as we move around the painting; one moment she is encouraging me to look at it from the side, at which angle the vertical bands and the brushstrokes seem to disappear completely, and then a moment later to join her near the window. From a few feet away, certain sections seem brilliantly white while others are grey; stepping back further, the contrast switches. As I change my position, her large gestural brushstrokes ripple across the surface, emerging and receding. Unsatisfied with the lighting, Corse switches off the studio lights and lowers the blinds on the windows, then plugs in a tungsten lamp. ‘See how it changes!’ she exclaims. ‘Look from over here.’ No longer grey and white, the painting has become a shifting palette of yellows, greens and blues. This is why still photographs cannot do justice to the fugitive and changeable nature of Corse’s paintings.

Corse tells me that she tries hard not to overthink her work before she’s made it. ‘I’m not interested in painting coming from thought. Thought is finite, thought is the past. By the time you have the thought, it’s over, behind you. It’s more about intuition and feeling.’ Nevertheless, throughout her career she seems to have had a number of ‘eureka’ moments when external circumstances pointed the way forward for her art. Her most famous epiphany was in 1968, when she was driving late one night in Malibu along the Pacific Coast Highway. She noticed how the white lines on the road caught the lights of her car and reflected them back, dazzlingly, and how they disappeared again as she moved past them. The road paint, she discovered, was – and still is today – mixed with tiny glass spheres, which she sourced and began applying to her own paintings. Corse does not mix them into her acrylic paint, exactly, but scatters them over a final brushed layer of gel medium, so they adhere in a skin that is minutely visible at very close quarters and which further away dissolves into an uneven and unstable iridescence.

Untitled (White Diamond/Negative Stripe) (1965), Mary Corse. Collection of Michael Straus

The perceptual phenomena that occur when you look at one of Corse’s White Light paintings are not to do with reflection, she points out, but refraction; inside the glass microspheres, light prisms, and the viewer catches different parts of the colour spectrum as he or she moves about the gallery. The mutable triangle that Corse sets up between the painting, the viewer’s eye and the light source (or sources) is analogous to another tripartite system that the critic Drew Hammond has outlined to describe how an experience of Corse’s work is formed: the artwork; the subjective perceptions compelled by the artwork; and the external conditions independent of the artwork that affect those perceptions. There is no such thing as an autonomous, objective form, Corse realised early in her career, since meaning arises only through a viewer’s subjective encounter with the artwork in a particular context. In a sense, the viewer generates the art. ‘It doesn’t really make any sense to talk about art at all,’ she observed in a film shot in 1969, ‘because art is the experience.’

Corse’s precocious early thinking about art can be traced to her remarkable education at a private junior high school she attended in Berkeley in the late 1950s. Her art teacher, a graduate of Los Angeles’ famous Chouinard Art Institute, introduced Corse to then avant-garde Abstract Expressionists such as Willem de Kooning and Hans Hofmann, as well as the Bauhaus master Josef Albers. She observed how colour relations and formal devices can achieve the ‘push and pull’ effect that Hofmann famously theorised, creating the impression of three- and even four-dimensionality within a two-dimensional space. ‘Early on, I realised, a painting can do something. It’s active,’ she tells me.

Corse graduated from Chouinard in 1968, but even during her student years she progressed through a staggering succession of formal and conceptual innovations, light years ahead of what most young graduates might hope to achieve. In 1964, for example, a red monochrome with a blue triangle cutting into its lower corner – Untitled (Red/Blue) – was a confident advancement of Hofmann’s theories adapted to a minimalist sensibility. That same year Corse began experimenting with shaped canvases, including Octagonal Blue, in which she mixed metal flakes into her acrylic paint, anticipating her later work with glass microbeads. The following year, vertical bands appear for the first time in paintings such as Untitled (White Diamond, Positive Stripe), a device that Corse still employs in her work. ‘The vertical bands,’ she says, ‘relate to you, rather than nature which is the horizon, horizontal.’

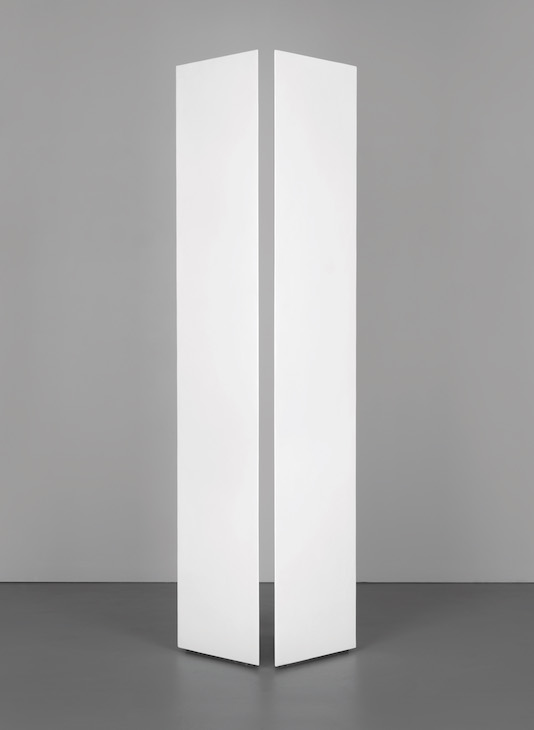

Untitled (Two Triangular Columns) (1965), Mary Corse. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Also in 1965, Corse built her first sculptural works, pairs of triangular columns painted white, which emulated the perceptual effects of two-dimensional works such as Untitled (White Diamond, Positive Stripe), the narrow gap between the two columns standing in for the vertical band in the paintings. When next she returned to wall-based works, it was no longer obvious whether she was making paintings in the conventional sense or sculptures: white-painted wood panels were encased in Plexiglas boxes an inch or two deeper than the surface of the paintings. Corse says she has always considered her work to be painting, even when, as with the hanging lightboxes that followed, their media included no actual paint. These lightboxes, the first of which she produced in 1966, became known as the White Light series, and inadvertently led to one of the most dramatic shifts in Corse’s thinking.

During this period, in accordance with the fundamental precepts of minimalism, also upheld in the 1960s by West Coast Light and Space artists such as James Turrell, Robert Irwin or Doug Wheeler, Corse sought to eradicate any evident trace of her own hand in her artworks. She sanded her Triangular Columns and Plexiglas-encased panels so that their painted surfaces seemed immaculate, machine-made. Although she constructed the lightboxes herself, along with the electrical componentry inside them, she achieved such a high finish that the final works seem like hanging squares of pure light. ‘At that time I was really looking for an objective truth, an objective reality,’ she says. ‘I wanted to make an object that was its own, that was on its own.’

As a consequence, Corse developed a technique for illuminating the argon tubes inside the lightboxes without having any distracting electrical cables connecting them to power sockets. She found that a Tesla coil, secreted in the wall behind thin plasterboard, could generate enough of an electromagnetic field to ionise the electrons in an argon tube across several inches of seemingly empty air. ‘There’s no big deal about the Tesla coil,’ Corse insists. ‘I don’t like ideas about my work getting too technical.’ Nevertheless, she became quite skilled in electrical engineering, and became increasingly ambitious with the size of her lightboxes and their attendant Tesla coils. (Corse has always worked confidently on a large scale, making paintings that have nothing to do with the cliché of feminine domesticity and everything to do with the immersive proportions of museums, and wall-spanning murals.)

The problem, however, was that the LA company that supplied Corse with the parts for her Tesla coils had a rule: above a certain power rating, they required a certificate of proper training before selling their components. Undeterred, Corse enrolled on a physics course at the University of Southern California. It was here that she was introduced to quantum mechanics and, most impactfully, the Heisenberg uncertainty principle which dictates that it is impossible to measure two properties of a wave – its position and its momentum, for instance – at the same time. Corse experienced another epiphany: ‘Nothing’s static in the universe. So why make a static painting? It’s an unreality.’

Untitled (First White Light Series) (1968), Mary Corse. Collection of Michael Straus

The paintings that arose from this formative period in Corse’s career are neither static, nor stable, nor measurable. ‘It was very difficult for me to go back to the brushstroke, after getting rid of it,’ she tells me. ‘That was a most difficult thing.’ In her White Light paintings, the first of which she made in 1968, she tore away from the pack of Light and Space artists – a movement that intersected in Southern California with Finish Fetish – to make brushy, almost expressionist paintings that have no equivalent in the canon.

Incredibly, she received nearly no recognition, on the West Coast at least, for her radical achievement. The prominent LA gallerist Nicholas Wilder had commercial success with her peers such as John McCracken and Bruce Nauman, but Corse admits that he ‘didn’t know what to do with me’. Instead, he introduced her to Richard Bellamy, the New York dealer, who represented her during the 1970s, until she signed with Doug Chrismas of Ace Gallery in the 1980s.

When I ask her if she resented being shut out of the male-dominated cliques of successful LA artists, she refuses to be drawn. It is unclear whether Corse was excluded from these circles against her will, or if she never really tried to enter them. The majority of Light and Space artists had their studios in Venice; during the 1960s, Corse’s studio was 15 miles east, in downtown LA, and then after 1970, 15 miles north-west, tucked away in the mountains with her family. It seems also to be the case that, especially in her student years, Corse was largely oblivious of – or uninterested in – broader trends in contemporary art of the time. She says, for instance, that she remembers seeing a shaped canvas by Frank Stella on the cover of Artforum in 1967, but thinking that it was very different from her own, of two years earlier. She claims she did not like Ellsworth Kelly until much later in life. East Coast modern artists were seldom exhibited in Los Angeles in those years.

Corse’s self-sufficiency is apparent throughout her life, but especially in her relationship to her art. ‘It came out of my early training to listen to the painting,’ she says. ‘That’s why it’s really a conversation with an abstract reality. I don’t need to look at another artist, because it’s the painting that tells me what to do.’ One painting leads to the next; in every painting there is something that bugs her, she tells me, and she is compelled to resolve it or explore it in another. Even though she is never satisfied, she is completely fulfilled by painting. ‘I paint for my sanity. Sometimes I feel like certain configurations align energies,’ she says. ‘Sometimes I crave a certain image like a drug.’

After 10 years of making her ethereal White Light paintings – a period during which she experimented with primary colour and also began her Black Light series, using both glittery black acrylic squares and microspheres scattered over black paint – Corse felt a need to reconnect with the ground, with the earth and her body. Between 1978 and 1981 she made her Black Earth series, in which large ceramic tiles are molded with a single cast made from the face of a rock, then glazed black. Corse tells me how she and a friend hiked through the Santa Monica mountains until they finally found a rock flat enough and big enough to take a plaster impression eight-feet-square; she drove back to the studio with it lashed to the bonnet of her car. She built herself a huge kiln outside her studio. Experts told her that it was impossible to fire something that big, but she used a Chinese method for distributing the heat which, she says, worked brilliantly.

All of the Black Earth pieces Corse completed, however, used four-foot tiles; the eight-foot tiles were difficult to get right, and often cracked because of their size. At an exhibition in 1981 at New York’s Clocktower Gallery, she showed one of the largest Black Earth paintings she had ever made, from 1978, comprising a 12-foot-square grid of four-foot tiles. The tiles were later redistributed into other works so that the piece, Untitled (Black Earth Painting) (1978), is no longer extant.

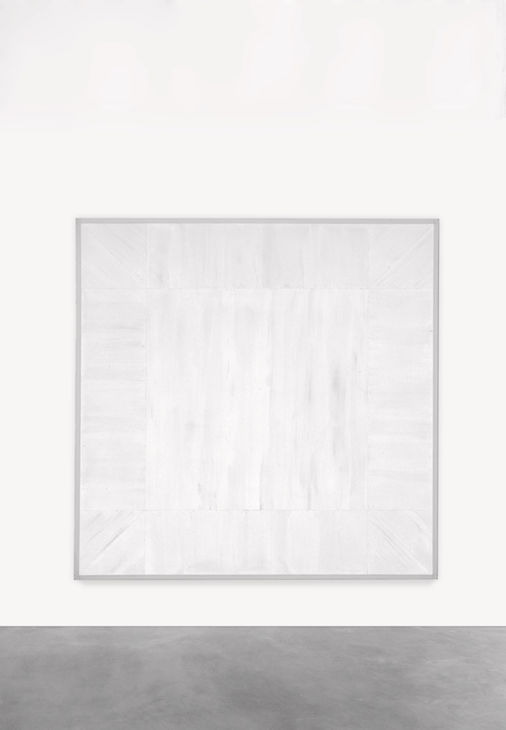

Untitled (Electric Light) (1968/2018) Mary Corse. Courtesy Lisson Gallery & Kayne Griffin Corcoran; © Mary Corse

It is a misunderstanding, Corse tells me, to imagine that each successive body of work invalidates the one which came before, or that she cannot revisit series that have been dormant for decades. One of the pleasing consequences of the current flurry of exhibitions of her work, she says, is that she gets to look at old work again; another is that she now has the resources to realise pieces that were too expensive or complicated to do at the time they first occurred to her. For her Lisson Gallery exhibition, for instance, she remade a lightbox from 1968 – Untitled (Electric Light) (1968/2018) – and she has plans to make several more, in different proportions and sizes. In her studio she shows me a square of black-glazed ceramic from the late 1970s, exhibited only once before, that sits flat on the floor and looks like rippling water, textured not with an impression of the rock face but with her fingers.

Before I leave, Corse wants to show me one of the largest pieces she has ever made, a White Light painting on the exterior wall of her new studio. The work, Untitled (White Light Inner Band) (2016), consists of four wide vertical stripes of microbeads and is 60-feet wide. It is partly shaded by a towering pine tree, which Corse’s 10-year-old son planted as a sapling – a promotional giveaway he got at McDonald’s. Corse declines to let me take a photograph; the painting is meant to be experienced at night-time when, she tells me, a tiny torch can activate the entire surface. Something about the situation is deeply touching: the quotidian origin stories of the tree and the pearlescent reflective bands, both utterly confounded by the gravity and beauty of the artwork, made in a place where few people will ever see it outside of a photograph, still fewer at the correct time of day.

‘Mary Corse: A Survey in Light’ is at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, until 25 November; DiaBeacon‘s long-term installation of works by Mary Corse opened in May.

From the July/August 2018 issue of Apollo: preview and subscribe here