In August 1956, the Whitechapel Gallery in London mounted ‘This is Tomorrow’. There were 37 young artists involved, split into 12 groups, exhibiting everything from optical art to readymades. Critic and co-organiser Lawrence Alloway said that the now-legendary exhibition constituted ‘a lesson in spectatorship’, but it was one you had to teach yourself, and fast. Alloway’s catalogue introduction was titled ‘Design as a Human Activity’; making their way around the gallery, looking this way and that, visitors would have felt that observing all these new designs was a pretty active task as well.

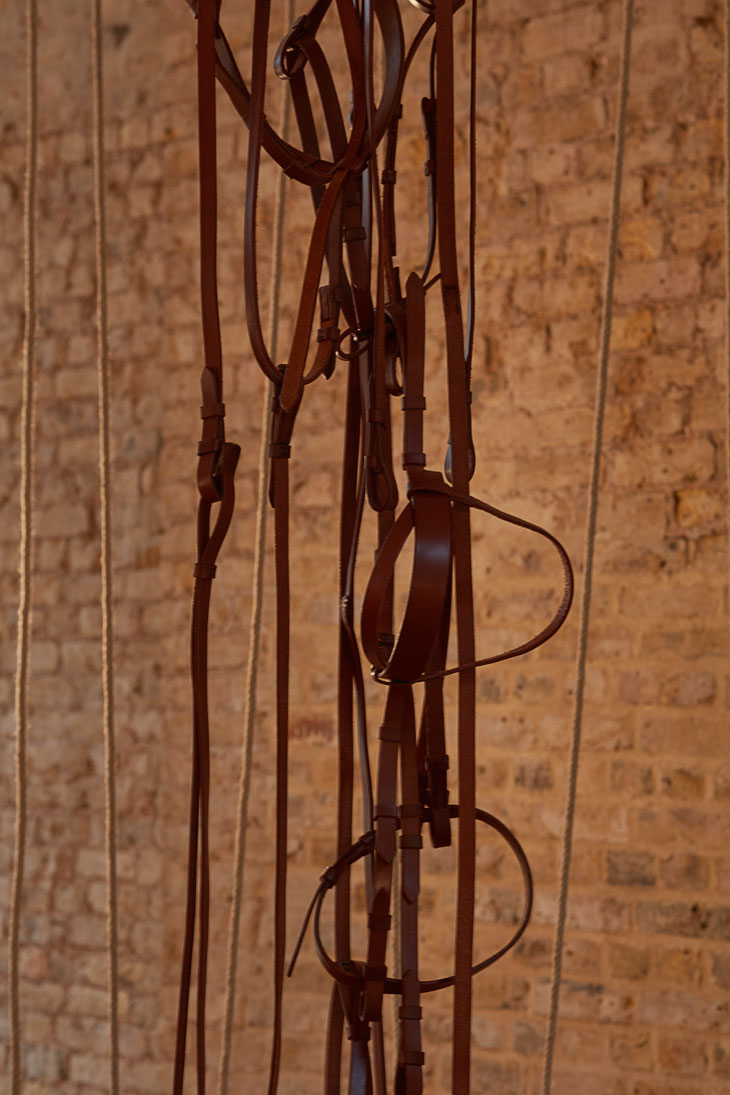

Sixty-one years later, there’s a new site-specific exhibition by Portuguese artist Leonor Antunes. ‘The frisson of the togetherness’ takes place in a sparse room of woven nets, strung cables, and freestanding objects; though the materials – leather, wood, rope – are Antunes standards, they also point back to their gallery’s past. Some speak of those days in 1956: for example, you glimpse Ernö Goldfinger in the cables hanging from ceiling and floor, figuring his banisters from 2 Willow Road. Some go back even further, to a history ‘This is Tomorrow’ knew. Leather harnesses hang in tangles, and conjure a 19th-century world in which the Whitechapel had stables for neighbours.

‘Leonor Antunes: the frisson of the togetherness’, installation view at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. Photo: Nick Ash

Lydia Yee, the exhibition’s curator, describes Antunes’s work as ‘like an answer, a reaction to the historical and architectural context of the place where [it’s] exposed’. But Antunes cares, more specifically, for how context becomes corrupted with time. While the phrase ‘This is Tomorrow’ is everywhere now – the art magazine, countless monographs, a Bryan Ferry album – not all of its participants still bask in its glow. Antunes often shines light on artists shoved into shadow, who are frequently women; this is her aim again today. To take one instance: both the freestanding teak and the cork-and-lino floor are cut into shapes designed by British sculptor Mary Martin, who worked on the ‘Environment’ section of ‘This is Tomorrow’. It’s a subtle ploy, but it’s potent. Without the smooth, disciplined Martin floor, there’d be nothing to give the Goldfinger cables their strength.

‘Leonor Antunes: the frisson of the togetherness’, installation view at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. Photo: Nick Ash

Because for every Goldfinger, there was an Alison Smithson. It was the latter who coined the phrase ‘frisson of the togetherness’, when she was talking in 1989 about fashionable kids. You couldn’t atomise their style, she said, you couldn’t treat it item-by-item; it was all about ‘how the items are put together and put on … the putting together, the frisson of the togetherness’. Put another way, styles are like interpretations: you trace them in the air. When an observer looks at the disparate elements of an exhibition, like they’d look at the parts of someone’s outfit, they’re trying to sketch how the pieces combine.

Antunes’s work reminds you that looking is a human activity, and humans have responsibilities to their past. ‘The frisson of the togetherness’ treats sculpture as a scene to be examined for clues: the leather tack caught in its tumble, the cables taut in their up-and-down shuttle. Walking around it is like entering a tableau of its predecessors, phantom presences back at work. You catch a glimpse of their crafts, one at a time, by walking, and turning, and looking from several angles. So it’s no surprise that, as Antunes has said, she can’t stand the word ‘installation’. It takes the dynamism out of memory – it suggests that what’s done is done.

‘Leonor Antunes: the frisson of the togetherness’, installation view at the Whitechapel Gallery, London. Photo: Nick Ash

‘Leonor Antunes: the frisson of the togetherness’ is at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, until 9 April 2018.