From the December 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

Visit a major gallery these days, and there may be more than meets the eye to some of your fellow spectators. In response to the climate protests that have rocked galleries and museums across the world, institutions have re-evaluated their security regimes – and the deployment of their staff.

‘Most rooms in museums are invigilated by people who are concentrated on looking at the work,’ says Robert Read, head of art and private clients at insurance provider Hiscox. ‘But what museums are doing now is realising that they have to hire plain-clothes people who are wandering round galleries who are socially profiling those attending these exhibitions. [They’re] looking at the people rather than at the work, to see who’s walking in, how they’re acting – does it look as though they’re about to do something, can they prevent it?’

Museums are, like every other institution, unwilling to talk about their security arrangements. But in a public letter published in October, the National Museum Directors’ Council (NMDC) in the UK stated that ‘with each attack we are forced to consider putting more barriers between the people and their artworks to preserve these fragile objects for future generations’. From bag searches to liquid bans and putting more works behind glass, these barriers are swiftly coming into view. Have these polarising demonstrations changed galleries, and the art world at large, for good?

Reactions have been severe. Just Stop Oil activists Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland were sentenced to 24 months and 20 months in prison respectively, for throwing soup over Van Gogh’s Sunflowers (1888) and causing £10,000 of damage to its frame at the National Gallery in London in 2022. (Joanna Smith, who smeared paint on the glass case surrounding Degas’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in 2023, got a lesser penalty of 60 days plus community service, although US law allows a maximum sentence of five years.)

Timothy Martin and Joanna Smith being arrested after smearing paint on the case that houses Edgar Degas’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1878–81) at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., in 2023. Photo: Ellie Silverman/The Washington Post via Getty Images

More than a hundred artists and art historians appealed for clemency for Plummer and Holland in an open letter, placing their action in the ‘well-established tradition of creative iconoclasm’ and even pointing to Van Gogh’s self-sabotage in cutting off his own ear. But only seven curators and gallerists joined their number, perhaps reflecting what appears to be a widely held frustration with climate activists continuing to target museums and galleries rather than governments and corporations. It is, in the words of one curator, ‘an exasperation that’s growing’.

Speaking on condition of anonymity, the director of one public museum in the UK believes that climate protesters are ‘really missing the way in which art can address these issues much more powerfully than the activist gestures do’. Having put on a number of exhibitions dealing with environmentalism and other causes, she is concerned about the effect of recent direct actions. ‘We need more efforts within museums and galleries to bring forward artists and curatorial visions that are actively trying to address the ways that the public, politicians and CEOs might get more serious about these issues. They’re the most important issues of our time, I’m with the activists on that entirely.’

Art has the power, she says, to ‘stretch the human imagination to think into a deeper period of time [about] our influence’, speaking of not only contemporary works but also the likes of Leonardo, whose depictions of natural disasters were manifold and who was, she says, ‘probably thinking about climate change more than any of the rest of us’. While there can be a sharp division between traditional collections and modern art – often installation or performance-based – that directly address political causes, she believes that there is scope for that to change. ‘Wouldn’t it be great if there was more pressure on museums and galleries to actually start doing this?’

Could climate protests be the catalyst for such a change? This museum director doesn’t think so. ‘They don’t get people to think about their core values. They get people to think about how they’re going to get out of the situation, deal with the situation, finish the situation. It creates a short-term, reactionary, risk-assessment-based set of considerations. If you can catch someone, an artwork can really pull someone outside of their usual thought processes, through its aesthetics, through its musicality, through its forms sometimes. At its best, that is actually what art can do.’

Some protests have targeted institutions for their sponsorship by oil giants or other companies linked to climate change. In a blockade that shut down Amsterdam’s most important museum in September, Extinction Rebellion said it was ‘incomprehensible that the Rijksmuseum can allow itself to be financed by ING, the largest financial driver of the climate crisis’. Just Stop Oil, however, has instead focused on institutions because of their public standing.

‘The point of the [Just Stop Oil] protests to me is very clear: it’s about public sphere, public life,’ says art historian John-Paul Stonard, who has found himself a lone voice in vocal defence of the group. ‘It’s about putting the urgency of the climate crisis at the forefront of the public mind in the most meaningful way possible.’ Pointing to how the National Gallery ‘looks down Whitehall’, he credits Plummer and Holland’s demonstration with not only forcing people to take a position on the existential destruction of climate change, but also shaping his own view of the urgency of taking action.

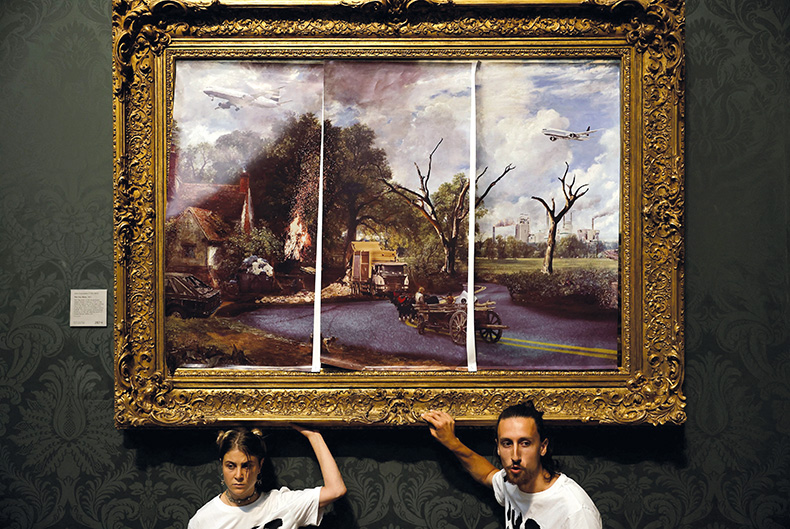

Just Stop Oil activists glued their hands to the frame of The Haywain (1821) by John Constable at the National Gallery in July 2022, covering the painting with an ‘updated’ version showing the countryside covered in roads. Photo: Carlos Jassop/AFP via Getty Images

Stonard rejects the claim that protests drive people away from the cause, saying that those who disagree with Just Stop Oil’s tactics are likely to consider other ways of taking action. But there is still a risk that cultural institutions will become more resistant to engaging with the issues. Despite extensive protests over a number of years – though in this case targeting it directly rather than using its prominence for public profile – the British Museum announced a 10-year sponsorship deal with BP last December.

Practically, protests bring the dual and sometimes conflicting roles of museums and galleries – conservation on the one hand and public access on the other – to the fore. At one extreme, Hiscox insurer Read says, ‘You wouldn’t allow anybody to see them, you’d just have [artworks] in a locked, climate-controlled room and that would be that,’ while, at the other, ‘You wouldn’t have any controls at all.’

Which brings us to glazing. It offers an additional level of protection to works, but few unglazed works have been attacked so far. ‘Glazed pictures can still be damaged, of course: things can seep in, and frames are sometimes as costly [as artworks],’ a curator at a major US museum says. ‘It’s one of the last scraps of protection that galleries can make. If that’s seen as a temptation, creating a target, that might just be under-appreciating the dilemma that museums have.’

Stonard says he was terrified for Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647–51) when its glass was smashed at the National Gallery last year. ‘They did use safety hammers, and I talked to them afterwards: they’d planned exactly where to hit the glass, exactly how many times, and exactly with what force. So it’s not wanton destruction.’

Having permitted photography in its galleries since 2014, the National Gallery has sometimes restricted it when major loans are on display. Lending galleries that don’t permit photography themselves can be queasy about allowing their works to be photographed on loan, often thanks to fear of damage (such as visitors backing into paintings while taking selfies). In recent years, the possibility of direct action has figured in this equation too, with foreign lenders writing such restrictions into loan agreements. If a protest cannot be filmed, the thinking goes, then it’s unlikely to take place at all.

Could pricier insurance premiums and fears of damage threaten loans altogether? ‘As soon as you get these enormous insurance issues, security issues, threat of occupation that goes well beyond reasonable protest and freedom of expression, and all of that, the screws just start to tighten around anything that artistic visionaries are trying to do in the first place,’ the UK museum director says.

In the UK, insurers consider the actions that have taken place in galleries as terrorism, because it meets the legal definition of serious damage designed to influence the government. This means losses are borne not by insurers but by Pool Re, the government scheme set up after the IRA attack on the City of London in 1992. Other countries have different legal definitions, so direct action might instead simply be considered malicious damage. No one has yet sought to charge protesters under terror laws.

‘It hasn’t resulted in significant insurance losses to date,’ Read cautions, noting that public collections are rarely insured commercially. ‘It’s resulted in a lot of publicity and, yes, some of the frames have been damaged, but the actual works themselves, by and large, have been less damaged.’ But if ‘they really want to play this out to the end’, he says, airport-style security will become the norm. ‘It will be the Gatwick, Stansted experience before you can actually get into the exhibition hall. Ultimately, we would all suffer as art lovers.’

From bag searches to body scanners, is entering a major museum beginning to resemble airport security? Photo: Chris Ratcliffe/Getty Images

The US curator speaks of ‘what a disturbing experience this is for those who are employed to protect the objects’. Staff who are not permitted to intervene feel ‘humiliated’ by having ‘failed’ to protect the artwork. ‘You can’t just remove somebody from a frame. It becomes a legal issue and you feel helpless. You’re just standing there like the cuckolded vigilante.’

Stonard acknowledges the tough predicament for galleries and their staff, but sees a bigger dilemma. ‘It must be difficult for people conserving works of art, restoring them. If you are a climate believer it must make your work a little bit meaningless, if you think “Why am I preserving this when it’s probably got 40 or 50 years left, before things break down?”’

If there is common ground to be found through conversations between institutions and activists, that will be an uphill struggle. None of the institutions contacted for this article agreed to be interviewed about demonstrations that had taken place in their galleries. Stonard says he suggested the National Gallery host a discussion with Anna Holland, only to be told: ‘There’s absolutely no way we can have them on the premises.’ The Tate took a different approach with protest art group Liberate Tate, inviting activists into the gallery. In 2016, it cut ties with BP, which the group had called for.

Recent protests, such as those after the sentencing of Plummer and Holland, have lacked the shock of the new. This wave of protest has yet to fizzle out but, eventually, tactics and targets will change. Meanwhile, an incident at the Art Gallery of Western Australia points to a future that will please neither side of the debate. Last year, a protester from Disrupt Burrup Hub sprayed the logo of oil and gas giant Woodside on the perspex covering of Frederick McCubbin’s painting Down on his luck (1889), saying the company planned to desecrate sacred Aboriginal rock art. In October, the Western Australian Museum (a different museum in the same cultural complex in Perth) announced that it was adding the graffitied perspex to its collection, apparently with the support of Woodside. Politicians have criticised the acquisition for ‘glorifying criminal vandalism’. But if acts of protest become commodified and classified as historical artefacts without altering the course of history in any way, that will be of far greater concern to the activists responsible.

From the December 2024 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.