From the December 2023 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In a prayer book belonging to Catherine of Cleves, dizzying visions of heaven and hell are punctuated by observations of everyday life in the Netherlands, says Diane Wolfthal, curator of a show about money and the Middle Ages at the Morgan Library & Museum.

Catherine of Cleves (1417–76) is renowned for two things: an unfortunate feud with her husband, the Duke of Guelders, and her book of hours – a prayer book for the laity. Books of hours were exceptionally popular in the 15th century; they offered a way for Christians to sanctify their time. The theory behind them was that at prescribed canonical hours, the book’s owner would recite certain prayers. Books of hours were sold to people of every level of income. Some were merely printed, but if you could afford it then you could, like Catherine of Cleves, get a very beautiful, personalised prayer book. They allowed men and women to pray at home. This book of hours is commonly dated to 1440, but the exact date is hard to pin down. We don’t know why Catherine commissioned it, but we do know that she marked it as her book.

While books of hours are often envisioned as offering private devotion, they could be brought to church to be shown off – they were status symbols too. There were criticisms of people bringing their books of hours to church and flashing them around. The more reformist churchgoers, particularly certain monks and nuns, said that these books should be for devotion and should not have pictures. Amid this debate, Catherine of Cleves clearly loved her art. Her book of hours is profusely and beautifully illuminated – with 157 illuminations.

The illustrations are attributed to the Master of Catherine of Cleves. We don’t have a name but the work was probably carried out by a workshop. Certainly, one person wrote the script, and probably another person added the gold leaf. The images in this book are of quite high quality, so it looks like the master of the shop had a large hand in most of them. The artist who worked on these illuminations – the so-called Master – came from the northern Low Countries, in what is now the Netherlands, which is where the Duchy of Guelders mostly was (the capital, Geldern, is in Germany). Many of the best-known illuminators – Simon Bening, and even Rogier van der Weyden and Jan van Eyck – came from Flanders in modern Belgium; the Master of Catherine of Cleves is generally deemed to be the finest of the North Netherlandish illuminators. He’s influenced by the South Netherlands, but he’s distinctly North Netherlandish: the sensibility of the North Netherlands tends to be simpler, plainer – this is the area that was going to become Protestant, while the south remained Catholic. He’s also known as a great storyteller – within limits: people have to know what the subject of the pictures is, they need to be looking at that image as they are saying the prayer for the dead, they don’t want you to show some gorgeous thing that’s not relevant, so illuminators relied on earlier models. But within that context, he’s quite original.

We’ve reached a point, though, where scholars don’t debate any more which hand did what, or even try to identify which illustrations are early or late – we just don’t know that much about the illuminator. Current scholarship places much more emphasis on the patron, because they were paying for it and they had to like the work. This book is not the product of an artist expressing himself, it is by an artist working on commission to please the patron. And the artist is further constrained because there was a text, and the images had to be not only iconographically recognisable – the reader needed to know which figure is Christ, who the saint is – but they also had to work well with the text. It’s like hiring a plumber: if they don’t fix the drip, they’re not going to get paid, they’re not going to get hired by other people. But of course, somebody as talented as this artist would be getting top commissions.

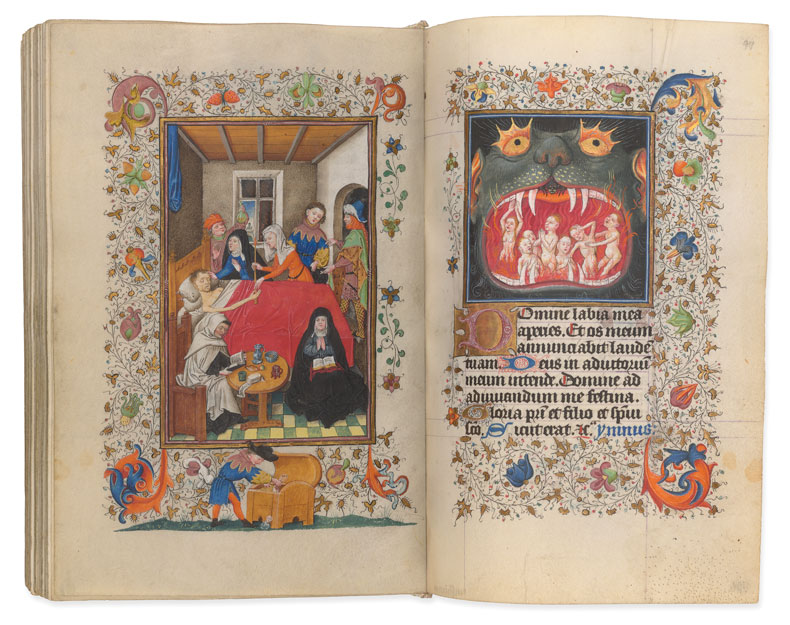

All the work on the page had to be planned ahead. The text was generally the first thing plotted out – usually the scribe would have written in the text first and left an empty space for the images and marginalia. On these pages of the book of hours, you can see the illuminated D at the start of the word Domine – the scribe will have left the square blank for the illuminator. Then, gold leaf was applied. Sometimes the miniature would have been done next, and sometimes the margin.

In some books of hours you will find instructions for the artists in the margin. They can be in the vernacular or in Latin, and they are usually snipped off or bound into the spine of the book so we don’t see them. Most of the artists were functionally literate, so there might be some instruction: ‘show a hellmouth, and Purgatory’, and the illuminator would paint that in. On these pages, all those little sparkling forms in the margin are gold leaf set by the gold leaf expert of the workshop. In this case, every little leaf has a black outline to give it some punch. Finally, the parchment bifolios were bound together.

The earliest art historians focused on describing each scene, and they wanted to identify every figure in each illumination. For instance, in this deathbed scene that opens Monday’s Hours of the Dead, the wife has been identified both as the figure holding the candle and as the woman praying in the foreground. We can’t really be sure. Deathbed scenes are very common, connected to the Office of the Dead, a text that you recite for other people who have died – most of the prayers in a book of hours were meant to be recited for yourself, but this one is a prayer for the dead. But while the deathbed scene is a common subject, it is rarely as elaborate as this one. The dying man is lying in bed; we can’t be absolutely sure whether he’s dead or alive but it appears that he’s waiting for the priest, who has not yet come. First of all, we should say the ideal death, then as now, is at home with your loved ones around you. But they also hoped that the priest would get there in time to administer last rites, because that would take years off Purgatory.

Monday Hours of the Dead from The Hours of Catherine of Cleves

The dying man is lying in bed. In the upper left of the miniature, you can see the doctor is holding up a vial – standard imagery for a doctor: a man inspecting urine in a vial. As one of the few bodily fluids they had ready access to, the urine would tell the doctor much of what he was going to figure out. A woman gives him a candle, which was part of the ritual for a dying person at this time. We also see that one of the shutters, and only one, is open. This may refer to the idea that the soul is, hopefully, going to ascend, and the open shutter might make it easier, but we’re not absolutely sure why it was open – it might merely be for aesthetic reasons; the artist might have just felt it was too claustrophobic to have all the shutters closed. What is agreed on is that the figure to the right of the woman with the candle is the dying man’s son. He’s very foppishly dressed, with a scalloped collar, and doesn’t seem very involved with the dying man, whom we assume is his father. Coming into the room is his buddy, who’s even more foppish, with fishnet stockings and elaborate headgear. They seem to be having some kind of tête-à-tête.

Figures usually identified as a Carmelite monk and a nun pray for the dying man while, in the foreground, the man’s son apparently removes gold from his father’s coffer – detail from Monday Hours of the Dead from The Hours of Catherine of Cleves

In the foreground of the main miniature is what most people think is a Carmelite monk, because his cloak is white above a dark tunic. This figure is reciting prayers. The woman in the foreground is frequently referred to as a nun. Again, she could be, but costumes at this time were often not fixed – unless you’re a leper and you have a clapper, or you’re a Jew and you have a badge, and it can be safer to be a little fluid. In the lower margin, you have the son again – you can identify him by his costume. He has already taken one money bag out of the coffer, and he’s seeing what else he can find. At the very least you can say he’s not interested in his father – he’s not looking at him, he’s not helping him – and then down at the bottom he seems concerned only with the money. Some people have suggested that the dying man is still alive when the son ransacks the coffer. You don’t have to be that narrative-led, but certainly, this is about the son’s relationship to his father.

The house that the dying man lives in is pretty well-to-do – a tiled floor, a wooden roof, shutters, carved wooden furniture – so he’s not starving. Then there are the objects on the table. It’s been said that these were objects used for administering last rites, but it may simply be that this is an artist who loves everyday objects. If you look at some of the other margins in the manuscript there are all kinds of quotidian items, such as shells, coins or bird cages. This is typical of the time – it illustrates what Erwin Panofsky called ‘a realism of particulars’. The artists of this period looked really, really carefully, and they loved to look and to help us to look. These details help to capture the reader’s interest by offering a new detail every day, something else to look at. It suits the function of the book to be this detailed.

Souls in Purgatory. Detail from Monday Hours of the Dead from The Hours of Catherine of Cleves

On the facing page we have a hellmouth containing Purgatory – it’s important to note this is not actually hell. Purgatory was a medieval invention: medieval Christians believed that it wasn’t decided immediately whether you enter heaven after you have died; if you had committed too many sins, the burning fires of Purgatory, which were extremely painful, would cleanse you of them. You did get Sunday off from the fires, though, which is why this is a Monday prayer – that’s the day all your loved ones’ souls go back into the fires, and you pray so that the souls of your family will have fewer years in Purgatory.

What this shows, then, is the next step for the soul of the dying man from the previous page, unless he’s been a saint and he’s going directly to heaven. But it’s also the next step for the heir, who is stealing – or is at any rate over-eager to get his hands on – the goods. He should be worried about going to Purgatory. This image is both for the living, to encourage them to think about what their sins are – will they go to Purgatory? – and to help the dead get out of Purgatory.

This is a particularly nice depiction of Purgatory: bright golden rays shine around the eyes of the animal-like head. He’s got fangs, pointed ears and a snout; inside his mouth, there’s a little creature, a demon. You’re not supposed to be looking forward to going to Purgatory, so anything that the artists can think of to make you shake in your boots is being depicted here. You can see the flames of Purgatory licking the sides of the creature’s mouth. And then, among the souls in Purgatory, we see a range of reactions. In some depictions of Purgatory the souls are shown as little children, but the souls here are adults – the artist has covered their pubic areas with the flames but you can see that some have women’s breasts and the males look like grown men. Some of these figures are praying, and some seem to be crying out in anguish. The one on the far right is said to be helping his friend next to him, maybe comforting him, though he’s also crying out. It’s yet another indication that this is an artist who doesn’t do the standard thing. He wants the picture to be interesting.

As told to Edward Behrens.

Diane Wolfthal is chair emerita in the humanities and professor emerita of art history at Rice University, and guest curator of ‘Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality’, at the Morgan Library & Museum, New York, until 10 March 2024.