Lubaina Himid

‘The past year has been extraordinary but slightly unreal, a bit like being in someone else’s life,’ Lubaina Himid tells me. By any standards, the last 12 months represent a significant stage in the artist’s 35-year career: alongside two solo exhibitions at Modern Art Oxford and Spike Island in Bristol, Himid was included in ‘The Place is Here’, a survey of black British art at Nottingham Contemporary. And, at the age of 63, she has been nominated for the Turner Prize – the oldest artist ever shortlisted after the award relaxed its upper age limit. It’s a moment of national recognition that feels long overdue.

That Himid suddenly finds herself in the spotlight is especially poignant, not least because her own work has consistently fought against invisibility, particularly in an institutional context. Since the 1980s, in works that are daring, political, and skilful, she has called for due acknowledgement of the black presence in British life. Her work, she says, demonstrates ‘that black people have contributed to European cities – many were built on the money earned from the slave trade – and have influenced the cultural landscape’. Naming the Money (2004), shown as part of ‘Navigation Charts’ at Spike Island, consists of 100 life-size cut-outs that represent African slaves at the royal courts of 18th-century Europe; each one is assigned a creative role, from artists and musicians to shoemakers. The installation evoked Bristol’s own history of wealth accumulated by the slave trade, but perhaps more potent was the work’s insistence that we walk among these hidden figures. ‘In a British setting, especially outside London and in an art gallery, it’s unusual to be in a space with 100 black people,’ Himid says.

Installation view of Naming the Money (2004), comprising 100 painted plywood figures and audio, on display earlier this year at Spike Island, Bristol. Photo: Stuart Whipps, courtesy Spike Island; courtesy the artist, Hollybush Gardens and National Museums Liverpool, International Slavery Museum

Cotton.com (2002) similarly affirms the contribution to Western life from artists across the African diaspora. A series of 85 small canvases painted in abstract patterns refers to an act of solidarity between Lancashire mill workers and enslaved African workers during the American Civil War. It’s an assertion of the rarely acknowledged impact enforced labour across the Atlantic had on the UK during the Industrial Revolution. Swallow Hard: The Lancaster Dinner Service (2007), in which beautifully painted black servants and greedy landowners are overlaid on English porcelain, confronts Lancaster’s links with the slave trade. Himid can be understood as a history painter, and much of her work’s force lies in its demand that we fill in historical gaps. From early on, she tells me, ‘I was trying to place black people into historical events, to make the invisible more visible’. She came of age in Britain in the 1970s, a time when ‘you rarely saw black people on the television, or in newspapers’.

I’m struck that, for more than 25 years, Himid has lived and worked in Preston – far from the centre of the UK’s art scene. ‘It’s a funny place to live,’ she admits. Born in Zanzibar to an African father and Lancastrian mother, Himid found herself briefly in Blackpool, the hometown of her maternal grandmother, after her father died suddenly. She grew up in London and studied theatre design at Wimbledon College of Art, before doing an MA in cultural history at the Royal College of Art, where she wrote a thesis titled ‘Young Black Artists in Britain Today’. Now Professor of Contemporary Art at the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan), Himid never meant to settle in Preston, but she paints an idyllic picture of her life there. ‘My house overlooks a magnificent park which has a river [the Ribble] running through it,’ she says. ‘I walk to work and there’s a lot of space and peace and time to make art.’ Preston has, she readily acknowledges, ‘helped me work.’

Women’s Tears Fill the Ocean (Zanzibar) (1999), Lubaina Himid (b. 1954). Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

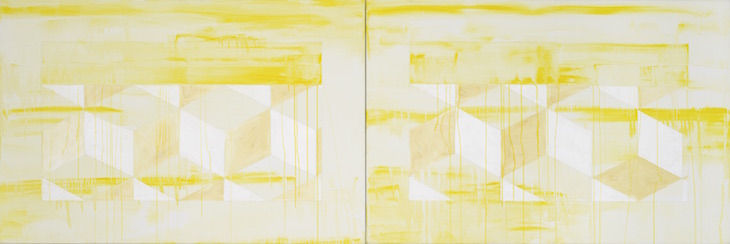

Meditations on home and belonging are threaded throughout Himid’s work, and memories of her birthplace appear frequently via African patterns (it’s no surprise that her mother was a textile designer). Perhaps most personal are the series of Zanzibar paintings that she made in 1998–99 after her first visit there as an adult. Featuring a recurring diamond motif – a reference to floor tiles and fabric patterns – the thin washes of paint that make up these lyrical, abstract canvases are like tears running down the canvas, sites of loss and mourning. They call to mind the sea, and accompanying associations of journeys and exile. Drowned Orchard: Secret Boatyard (2014), comprising 16 thin wooden planks painted with shells, fish and boats, speaks not only of fatal crossings but the global movement of people and culture. Today, in the midst of an international refugee crisis, such works take on a renewed resonance.

In London during the mid 1980s, Himid curated a number of seminal exhibitions, emerging as a keen champion of black women artists. These included ‘Five Black Women’ at the Africa Centre and ‘Black Woman Time Now’ at Battersea Arts Centre, both in 1983, and ‘The Thin Black Line’ at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1985. Her role as a curator continues today. Currently on display at the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool is a selection of works by women chosen by Himid from the Arts Council Collection (until 18 March 2018) while, in 2015, she curated ‘Carte de Visite’ at Hollybush Gardens, the gallery that has represented her since 2013, showing new work by three black women artists who ‘wouldn’t necessarily normally show there’. I ask one of these artists, Helen Cammock, what it was like to work with Himid: ‘She is an artist/curator who utterly trusted my instinct, who was there to talk ideas through, to ask questions, to make suggestions, but most importantly, to encourage me to make what I wanted with confidence and courage.’

Freedom and Change (1984), Lubaina Himid. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

Providing opportunities for other black women is one way in which Himid’s designation as a black feminist – dual identities which ‘are not separate’ – can be seen in practice. Reclaiming female agency is also a notable feature of her own work. Freedom and Change (1984), shown in Oxford, subverts a Picasso painting, transforming the female figures into two black women. Cultural appropriation enacted by modernists such as Picasso meant Himid ‘felt quite at ease appropriating back again’. Cotton.com includes a long gold plaque engraved with the words: ‘He said I looked like a painting by Murillo as I carried water for the hoe gang, just because I balanced the bucket on my head’. In giving agency to this female slave, Himid also warns against the romanticising effects of art in the face of human misery.

This engagement with art history also finds expression in A Fashionable Marriage (1986), a large-scale tableau of cut-outs shown in Nottingham and now the centre of Himid’s Turner Prize exhibition at the Ferens Art Gallery in Hull. In its theatricality, the work attests that Himid’s background in stage design remains ‘ever present’. Drawing on Hogarth’s critique of 18th-century society in Marriage A-la-Mode (1743–45), Himid’s installation is a damning indictment of UK society, including the art world, in the 1980s, with Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan as the countess and her lover alongside a critic and a dealer. When this work was made, Himid was at the centre of the British Black Arts Movement – the wider developments of which were examined in ‘The Place Is Here’ – which asked urgent questions about black identity and cultural representation against a backdrop of racial tension and divisive politics. Himid’s pivotal role as a curator in the 1980s should also be framed in this context.

How much has changed since the 1980s, given the extent to which immigration and identity remain central to British politics? Himid senses parallels between that period and today. ‘Many of the issues brought up in the ’80s were not dealt with properly,’ she says. ‘We’ve reached a time again where the history of the black presence in Britain isn’t being told in the positive way it could be.’ In the series Negative Positives from 2007–15, Himid attempts to reclaim the stories of black people from their stereotypical media representations by painting over pages from the Guardian, often with African patterns.

Himid attributes the recent interest in black art in the UK – including Tate Modern’s ‘Soul of a Nation’ exhibition – to the fact that current influential figures in arts organisations are ‘young enough not to be afraid of the work made by black artists’. ‘They are curious to know why their predecessors couldn’t deal with it and are eager to know how, while being produced behind the scenes and below the radar, it shaped the politics and creative thinking of the past 30 years. Change has come, it’s what we do with it that matters.’

Le Rodeur: The Lock (2016), Lubaina Himid. Courtesy the artist and Hollybush Gardens

The question of visibility is clearly something that continues to inform her work. A strange new painting, Le Rodeur: The Lock (2016), draws on the story of a 19th-century slave ship in which all bar one of the slaves went blind, resulting in many being thrown overboard. There’s a lurking dread in this work that seems to transcend time and place; the sea is once again an uneasy presence. While her recent work, she tells me, is ‘freer and more experimental’, it continues to mine ‘the depths of despair, the pain of loss, and an understanding of what actually matters to me’. Having made so much work – ‘the years went by and I just kept making’ – I wonder what drives her today: ‘a clear realisation that I have little time left to say what needs to be said given how long I’ve already been working’. Next year, she has a show planned for Hollybush Gardens, alongside new commissions for the Glasgow International Festival and BALTIC in Gateshead.

A further facet of Himid’s practice that has received less attention is her role as a teacher at UCLan, which she sees as inseparable from her role as an artist. ‘I just like to talk about art all day,’ she says, acknowledging that ‘the conversations I’ve had with art historians, artists, art lovers, and students during the past decades have been the most influential and informative. Hopefully these won’t stop now.’ Jade Montserrat, whose PhD is being supervised by Himid and is an emerging artist in her own right, tells me that Himid ‘is unceasing with ready and seemingly effortless seeds of wisdom, advice, encouragement, support, warmth, care, direction, and nourishment for the soul and intellect’. It’s an affirmation that hints at Himid’s own influence on a younger generation of black artists.

Indeed, in writing about her work, and talking to her colleagues and collaborators, I have encountered this warmth and generosity repeatedly. Alan Rice, Himid’s co-director at the Institute for Black Atlantic Research at UCLan, emphasises her risk-taking and fearlessness – ‘she is unafraid of what feathers she might rustle’ – and makes clear that her work on memory and slavery over the last 30 years marks an outstanding contribution to art and ideas. Rice also outlines Himid’s desire to connect to audiences beyond the academic, recounting how she spent much of a recent conference tweeting and instagramming. ‘Typical Lubaina,’ he says, ‘working for the common good whilst having the time of her life.’

Imelda Barnard

The Winners | Personality of the Year | Artist of the Year | Museum Opening of the Year | Exhibition of the Year | Book of the Year | Digital Innovation of the Year | Acquisition of the Year | View the shortlists

The Winners | Personality of the Year | Artist of the Year | Museum Opening of the Year | Exhibition of the Year | Book of the Year | Digital Innovation of the Year | Acquisition of the Year | View the shortlists