From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.

In November 1908, a wealthy French banker named Albert Kahn set off on a trip around the world. Accompanying him were his business manager and his chauffeur. But this was no ordinary business trip and his young chauffeur, Albert Dutertre, wasn’t there to drive. In the months leading up to their departure, Kahn had sent Dutertre to train with a specialist in taking photographs and developing photographic plates. He also sent him to Pathé Studios for lessons in moving-image making. The trio’s journey from France to the United States, Japan and China and back via Malaysia, Sri Lanka, the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean was recorded in 3,500 stereoscopic plates and 1.5 hours of film. The trip was, in a sense, a trial run for what was to come.

On his return to Paris the following year, Kahn attended a magic-lantern projection of slides showing scenes from Algiers and other parts of North Africa in dazzling colour. Autochrome plates, which produced the first-ever full-colour photographs, had only recently been made available commercially by their inventors, the Lumière brothers. Kahn wasn’t the first rich businessman to be seduced by this new technology (which was exclusively expensive). By 1908 Lionel de Rothschild was also experimenting with the autochrome and left 733 glass plates in the family archive. But Kahn, as his trip with Dutertre indicates, seems to have shown little interest in mastering the art of photography himself. Rather, it was the ideal vehicle – and autochrome could be the principal medium – for the ambitious project he now launched: Les Archives de la Planète, a visual survey of the world in the rapidly shifting 20th century. ‘I want to use these techniques on a grand scale,’ he wrote, ‘to capture definitively all the aspects, practices and methods of human activities whose absolute disappearance is merely a question of time.’ Beyond a wish to record slices of the world that were soon to vanish was an even higher purpose: a pacifist, humanist and universalist, Kahn believed such a project, by encouraging in the elite figures he had access to an understanding of other cultures, would lead to social progress and universal peace. Over 22 years between 1909 and 1931, photographers and camera operators sent by Kahn to 50 countries around the globe produced some 72,000 autochromes, as well as 4,000 black-and-white stills and 100 hours of film footage. Amazingly, those many thousands of delicate glass plates have survived at Kahn’s former home in Boulogne-Billancourt, west of Paris. They amount to the largest collection of early colour photography in the world; and yet Kahn and his collection are relatively unknown, even to Parisians.

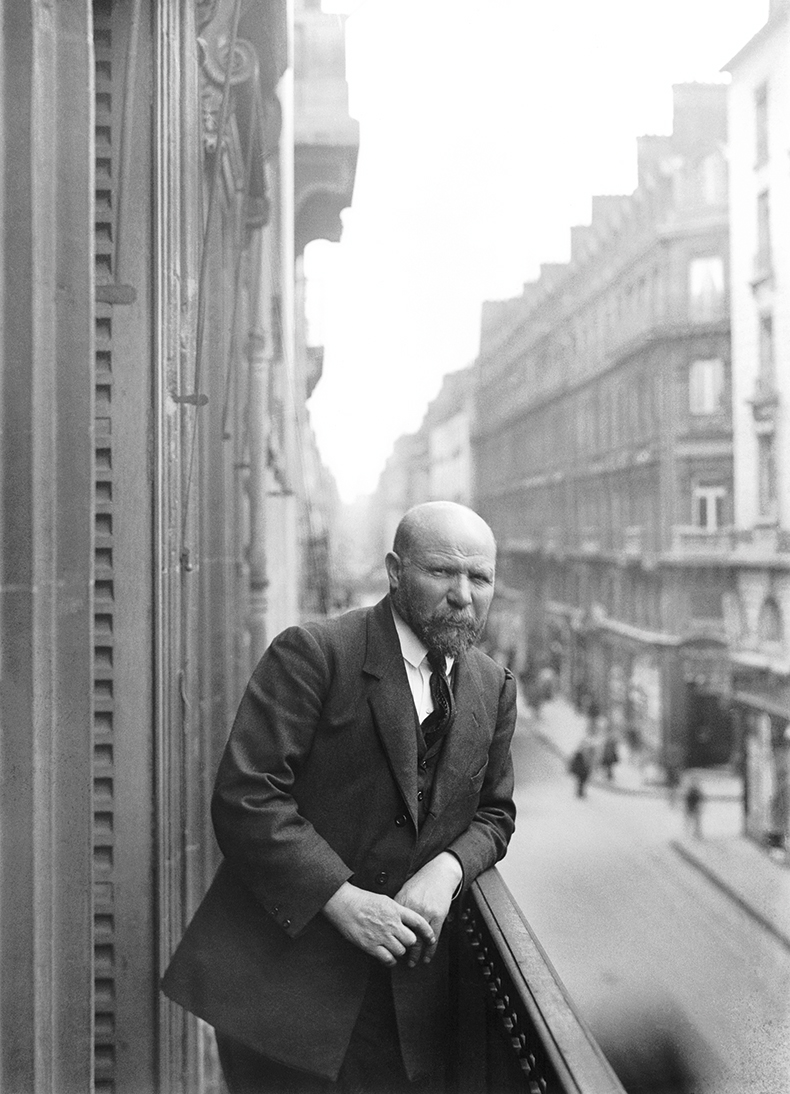

Albert Kahn on the balcony of his bank, 102 rue de Richelieu, Paris (1914). Georges Chevalier. Musée Albert Kahn, Paris © Département des Hauts-de-Seine/Musée départemental Albert Kahn – Collection Archives de la Planète

Born the son of Jewish cattle merchants in Alsace in 1860, Kahn had come to Paris at the age of 16 and by his thirties made a fortune, mainly from speculating in gold and diamond mines in South Africa. Meanwhile, however, he had resumed his studies under the tutelage of the philosopher Henri Bergson, who was his contemporary and who became a friend; to him Kahn admitted that success in business was ‘not my ideal’. In 1898, the same year he set up his own bank on the rue de Richelieu, Kahn financed the first of his ‘Autour du Monde’ scholarships – generous travel bursaries (the equivalent of around €60,000) for young doctoral graduates. Inspired by Bergson’s ideas and his own experience of travel for business, Kahn explained: ‘The more they [young teachers] acquire intelligent experiences to support the lessons they teach, the more these lessons will impact those who are listening to them. Travel can provide this experience in an intense way.’ The scholarship programme would last 30-odd years and later opened up to women and students from other countries – including Japan, a country for which Kahn had developed a passion after business had taken him there. For the boursiers, there were no strings attached. ‘I ask only one thing of you,’ Kahn told them; ‘it is that you keep your eyes wide open.’

In practice, many of them returned to show their findings, meeting at Kahn’s home in Boulogne-sur-Seine. Having bought in the 1890s a modest hôtel particulier near the river, Kahn gradually acquired surrounding plots of land to end up with four hectares. There he planted French- and English-style gardens; an orchard and rose garden; an alpine wood and a forêt vosgienne, with pine trees and rocks of pink sandstone transported by train from the Vosges, near his birthplace. Largest of all was a Japanese-style garden, with wooden bridges, a four-floor pagoda, a tea pavilion and two 19th-century wooden houses, shipped from Japan and reassembled by Japanese craftsmen. In these surroundings, meetings of the ‘Autour du Monde’ were held, increasingly attracting influential members and guests – who from 1909 onwards were given screenings of photographs and films from the Archives de la Planète. ‘There was something unique in the air,’ wrote Bergson in the 1930s, ‘eminent men from all over the world, notably those who embraced the dream of a better and more well-organised humanity.’

By 1936, however, Kahn was bankrupt, his fortune wiped out by the Wall Street Crash, and his estate at Boulogne was acquired by the Département des Hauts-de-Seine – which was more interested in the gardens than the image collections. Somehow those collections survived the war – and the Nazi occupation of the estate – and inevitably, as time went on, the sense of the Archives de la Planète’s importance grew. In the late 1980s a gallery was built to show something of them, but the space was small and largely ignored by people who came for the garden.

That structure has now been incorporated into a new museum funded by the Département des Hauts-de-Seine at a cost of €60m. Designed by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma, from the main approach off a roundabout in Boulogne-Billancourt the building won’t be so easily ignored – it’s something of a metallic juggernaut. Inside, however, where wood and bamboo dominate and horizontal oak slats evoking sudare filter views through to the garden beyond, the choice of Kuma for this Japanophile’s utopia makes immediate sense. ‘Kengo Kuma’s proposal [in 2012] was very convincing because of its clever use of the land area and integration of the former museum,’ says Nathalie Doury, director of the museum since 2019; ‘but also because of its intimate understanding of the connection between the image collections and the garden.’

Rabindranath Tagore (1861–1941) in the Avenue of Roses (1921). Musée Albert Kahn, Paris. © Département des Hauts-des-Seine/Musée Albert Kahn – Collection Archives de la Planète

In one sense, these two elements have a direct natural connection. Of Kahn’s 72,000-odd autochromes, around 2,500 feature his parc à scenes in Boulogne. In most cases, the garden alone is the subject, and these images have proved invaluable for the restoration and replanting projects that have been necessary over the decades. Other plates record visits from distinguished guests. In one particularly striking photograph taken in June 1921, the Bengali poet and polymath Rabindranath Tagore stands with pink roses tumbling down around him from boughs arching across the pathway. Against this riot of colour, Tagore, with his white hair, beard and tunic and his steady gaze towards camera, looks other-worldly. Perhaps this has something to do with the almost three-dimensional quality of these vivid glass plates. Perhaps, too, it’s the shock of seeing in colour subjects we’re used to seeing in monochrome.

Kahn was not alone in his creation of a ‘collection’ of gardens from around the world; it was a fashionable concept for the wealthy in the late 19th century. One of the subjects among Lionel de Rothschild’s autochromes was in fact his cousin Edmond’s gardens nearby on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne; he was creating a similar (if much grander) series of landscapes – and even poached Kahn’s Japanese gardener for the purpose. But if his Archives de la Planète aimed, curiously naively, to foster world peace through an understanding of other cultures, then his gardens were an extension of that idea. As a universalist, like his friend Tagore, Kahn presumably prized them not so much for their exoticism but for the idea that they might begin to feel familiar. In presenting the gardens and the collection as two sides to the same coin, the new museum aims to restore the atmosphere and function of the estate in Kahn’s day. ‘When he invited his guests they were always given a tour of the gardens,’ Doury explains. ‘It was a message about the diversity of the world. Then there were projections of the Archives de la Planète, cocktails, dinner, and talks. So that was the way he built his influence and promoted his ideals.’

Inside the Albert Kahn Museum in Paris. Photo: Julia Brechler; courtesy Musée Albert Kahn

The Archives are at the heart of the new museum, conceptually if not physically. Moving from the entrance hall on the ground floor through to the permanent exhibition space, the first thing the visitor encounters is what the museum calls the Inventory Wall: 2,680 transparencies made from digital scans of the autochrome plates, each reproduced at its original size (9 x 12cm) and illuminated from behind. ‘One of the big challenges was how to display the autochromes,’ Doury says, ‘because we cannot display the original plates, and we didn’t want to make prints; we really wanted to show them as they were meant to be shown, which is basically through light – projected, on screens, on a lightbox, or backlit, as they are here.’ The wall also responds to the challenge of how to give a sense of the vastness of the collection. As Doury explains, they decided to show one in every 27 plates from the Archives, starting with plate number 1 – a landscape view of the Port of Algiers from 1909 – and then moving to number 28, and on accordingly. Since the plates were numbered in chronological order, you move with them through time.

And, of course, space. One of the delights of this display approach is the juxtapositions it throws up. Pick a section at random and you’ll find, say, a group of Old Masters at the Kunsthistorisches in Vienna in 1913 next to women from Thessaloniki in traditional dress, taken by a different photographer around the same time; move on and you might notice a perfume-seller in Cairo in February 1914 below a woman cloaked in a brilliant-red cape in Claddagh, Galway.

Around this point, of course, a different kind of image emerges. Here, suddenly, men in Kahn’s garden are posing in blue uniform. And while one photographer in 1915 was recording a colourful temple scene in northern Vietnam, another was capturing the ruins of a shelled cafe near Nancy. Kahn had in August 1914 set up an emergency relief committee to centralise government welfare groups and raise funds to provide clothing and food to those most in need. His desire to document every facet of life – in war as in peace – saw him encouraging his photographers (with authorisation from the Ministry of Public Instruction) to produce ‘views of the theatre of war’. His pacifism did not preclude patriotism and he supported the French government’s propaganda department in making images of the Front. As a result, the museum holds the largest collection of colour photographs of the First World War, with subjects ranging from the human and architectural toll to more quotidian scenes between the fighting: a soldier sitting on the cobbled ground of a deserted town square, eating his lunch; Senegalese recruits washing clothes in stone troughs.

Reims, Marne, Champagne: French soldier with his kit and bicycle (1917), Paul Castelnau. Musée Albert Kahn, Paris. © Département des Haut-de-Seine/Musée Albert Kahn – Collection Archives de la Planète

Time spools on, and we reach images of the war’s aftermath. ‘These are posters for the liberation bonds,’ Doury points out, ‘which were the big borrowing endeavour by the government to rebuild the country […] And here is the table on which the Versailles Treaty was signed – we didn’t cheat; this image actually came out of our one-in-every-27 plate system.’ Seemingly confirming that claim are occasional images of psychedelic patterns in lurid purple, yellow and green, where the plate’s chemical emulsion destabilised.

Another image type repeats itself across the hundreds here, too: figures of all ages, style and nationality, posed against a green velvet curtain. This was Kahn’s visual visitors’ book, and a dedicated interactive display elsewhere reveals the variety and calibre of his many guests. This hall of fame features no less than 20 Nobel prize winners, and other luminaries including Anna de Noailles, Fujita Tsuguharu, Paul Hazoumé, Louis Lumière and Thomas Mann. A strong contender for winning portrait goes to the writer Colette, swathed in furs and apparently cooing to the French bulldog clutched in her arms. There is the sense that, just as Kahn was sending photographers out to the world, the world was coming to him in Boulogne.

The next stage for the Inventory Wall, Doury says, is to add a digital layer to each of these transparencies, so that you can scan an image via an app on your phone and bring up the caption. And while for this visitor at least, there is something delicious about pressing your face up close to these diminutive vistas into other worlds – like a supersized Alice peering through a keyhole – to show the Archives in a more practical way, the permanent gallery’s central space allows you to explore the collections thematically via tablets, which project images and films on to the wall. This was, after all, the way Kahn intended them to be seen.

His former projection room, beyond the rose garden, is one of several outbuildings that have been restored and requisitioned for the museum itinerary. Renamed La Fabrique des Images, it is now dedicated to the photographers of the Archives – their expeditions, process and equipment. And what a lot of equipment there was, both cumbersome and fragile: heavy cameras, stands, boxes of autochrome plates, sometimes even portable laboratories for developing the plates in the field. Kahn ensured a soupçon of campaign style, however, by commissioning custom trunks from Louis Vuitton complete with compartments for photographic chemicals and other kit, and a striking red toile exterior. (In 2014, Nicolas Ghesquière would refer back to Kahn’s design – including his signature three white ‘X’s, which identified the trunks as his – for the Vuitton ‘Petite Malle’ handbag.) One of the trunks is on display here, and the museum has taken it as inspiration for the display motif in this room: case-like structures open up to reveal film footage and backlit autochromes, or animations to explain the autochrome process. It’s gimmicky – and the height of some of these elements indicate they’re aimed primarily at children – but tastefully so.

One of the challenges with the autochrome was how much longer, relative to black-and-white photography, exposure time was. Mostly that meant avoiding crowd scenes, or accepting that the figures in the photographs would be blurred. An interesting exception to this is displayed in one of the cases here: shots taken in January 1914 of thousands of worshippers at Friday prayer outside the Jama Masjid of Delhi, one of the largest mosques in India. The photographer, Stéphane Passet, wrote to Kahn afterwards: ‘The crowd carried out synchronised prostrations lasting several seconds, so I now have colour images the like of which you have never seen before.’ Passet made film footage of the sequence too; Kahn’s photographers worked hard, and Passet – who on the same trip attempted access to Afghanistan via the Khyber Pass, but was turned back by the British – was at pains to let his employer know: ‘I am hardly in appetite and assure you that I am not on a pleasure trip,’ he wrote in another letter.

Corfu, Greece: two Corfiot women in costume (1913), Auguste Léon. Musée Albert Kahn, Paris. © Département des Hauts-de-Seine/Musée Albert Kahn – Archives de la Planète

That the Archives project operated under a rigorous set of objectives and guidelines becomes clear. In 1912, Kahn appointed the geographer Jean Brunhes as its director, who worked closely with the opérateurs, and occasionally travelled with them. One display here shows sequences of autochromes by Auguste Léon of men and women in traditional dress in Corfu, Kastri and Malakasa in Greece, and in Cetinje in Montenegro. The subjects are photographed from the front, side and back, individually and in groups. The same close attention is paid to objects, too. During a search through the collection online (some 60,000 images from the collections have been uploaded), I came across photographs of a table laid with an assortment of mysterious accoutrements in Hanoi in 1915, with the caption ‘Utensils of an opium-smoker, middle class’; then a few plates later, a grander-looking table display: ‘Utensils of an opium-smoker, upper class’. In Paris especially, opérateurs were sent back to the same locations after an interval of several years, to chart the changes that were occurring in the fabric and society of the city.

Around a dozen photographers were involved in the Archives project over the 22 years that it was in operation. They included one woman, Marguerite Mespoulet, who made the project’s only expedition to Ireland, in May 1913, at a critical period for the country. Having studied Celtic history at the Sorbonne, Mespoulet was a former ‘Autour du Monde’ scholar (more information on the scholars and their work has been included in the museum’s inaugural temporary exhibition in the upstairs galleries of the main building). That red-cloaked woman from Galway on the Inventory Wall was hers, one of a series of images recording a Gaelic way of life on the verge of extinction. Her 73 autochromes are among the earliest known colour photographs of Ireland.

Of Kahn himself there are, ironically, few photographs – perhaps a dozen altogether. There are occasional glimpses of him on film, walking through his garden. He is, for all his many projects and contacts, something of an enigma. When the département took over his property in the 1930s, Kahn was allowed to stay on in his house. He died in 1940, having witnessed the arrival of another world war, and having been required by German decree to register himself as a Jew, number 59582. His sense of failure must have been acute. But while his vast photographic project may not have achieved what he hoped it would, it remains an extraordinary legacy; one that, at last, has a museum worthy of it.

From the November 2022 issue of Apollo. Preview and subscribe here.